(UroToday.com) Following two presentations from Dr. D’Amico and Dr. McBride looking at docetaxel and abiraterone acetate, respectively, as treatment intensification for patients treated with radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for patients with locally advanced prostate cancer, Dr. Vapiwala provided a discussant overview of these data and helped to contextualize how we may apply them to our practices in the Prostate, Testicular, Penile Poster Discussion session at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting.

She began by exploring the many facets of treatment intensification, highlighting that medical oncologists will want to intensify therapy for healthy, motivated patients with bad disease. In doing so, they may consider adding on cytoreductive surgery to the primary and lymph nodes; more, or newer, drugs including androgen-axis targeting agents or chemotherapy; and higher-dose, “bigger” radiotherapy with dose escalation and elective nodal irradiation. Rather than “adding on”, an alternative may be to treat longer, offering 3-years of androgen deprivation therapy. Finally, we may start earlier, utilization agents earlier in the disease process (shifting indications).

She then focused on the potential to “add on” with more or newer systemic therapies. Typically, we begin both clinical practice and research protocols with a backbone on androgen deprivation. Subsequently, next generation anti-androgens targeting either androgen biosynthesis (abiraterone acetate) or the androgen-receptor (enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide), or chemotherapy. Further, PARP inhibitors can be considered, as is currently being explored in the NADIR trial in combination with radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy in men with high-risk disease. Finally, she emphasized that radiotherapy can be a systemic therapy as well, including radium-223. In the context of the data presented at ASCO 2021, we consider treatments in the first three of these categories.

She then delved into the rationale for docetaxel, in combination with radiotherapy. Docetaxel has been proven to prolong survival in men with metastatic disease either in the castration sensitive or castration-resistant disease space. Thus, there has been ongoing interest in its use earlier in the disease process. In parallel, radiotherapy and ADT in combination prolong survival for patients with locally advanced disease.. However, there are incumbent risks with these treatment approaches. Thus, there was interest in combining these approaches given, in part, the non-overlapping risk profiles Prior to work presented by Dr. D’Amico at this year’s ASCO meeting, 6 six prior phase III trials have been performed assessing docetaxel in unfavorable-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer. Four of these have been negative and two have shown an initial overall survival benefit without evidence of improved prostate cancer specific mortality. As a result, the category 1 recommendation for docetaxel in very high risk disease was removed from NCCN guidelines.

However, a key hypothesis in the work of Dr. D’Amico comes from a paradoxical observation (that docetaxel improved overall survival without improving prostate cancer-related mortality): that docetaxel co-administration may reduce radiotherapy-induced cancer incidence and death. To assess this, they performed an RCT of docetaxel among men with unfavorable risk prostate cancer undergoing radiotherapy and ADT.

D’Amico and colleagues found no difference in overall survival though they did importantly show that rates of radiotherapy-induced cancers were lower in patients who received docetaxel (HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02-0.97). This is a novel finding, demonstrating a protective effect of docetaxel in radiotherapy-induced carcinogenesis, highlights the importance of radiation-induced cancers. Radiobiologic data clearly demonstrate that the non-targeted effects of ionizing radiotherapy may led to its carcinogenic potential through cell cycle arrest, genomic instability, and DNA repair abnormalities.

Nambiar et al. Mutation Research, 728(3), Nov-Dec 2011, p.139-157

How modern approaches, including proton therapy, and the use of concomitant systemic therapies may mitigate this risk from radiotherapy is unclear.

Dr. Vapiwala emphasized that the treatment of prostate cancer is a good model for studying radiotherapy-induced cancers given the long natural history and natural controls of surgically treated patients. Highlighting data published by Brenner et al. in 2000, she emphasized that patients with prostate cancer captured within the SEER dataset who underwent radiotherapy had a lower risk compared to the general population, but a significantly increased risk compared to those undergoing surgery. At 5 years following diagnosis, this was quantified as 1 solid tumor for every 125 men treated. For those who survival 10 years following treatment, this rises to 1 tumor for every 70 men treated. Predominantly, these are bladder cancer, rectal cancer, and in-field sarcomas. If we restrict only to those under the age of 60, there was an increased risk of cancers for men treated for prostate cancer with radiotherapy, compared to the general population.

She then discussed two studies (one relying on a sample of patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering and one from the Munich registry). The analysis from MSK demonstrated no significant differences after adjusting for age and smoking status. In the Munich registry, the authors found significantly higher rates of secondary cancers among patients treated with primary radiotherapy compared to surgery alone, with intermediate rates among those who received radiotherapy following surgery, postulating that this may be explained by older age, lifestyle, or comorbidity differences.

She concluded that, despite heterogeneity between studies, there is a small increased risk of secondary cancer for patients treated with radiotherapy. Further, older techniques may contribute more substantially to carcinogenesis. Third, she emphasized that there is a latency period, with most secondary cancers occurring 5 years or more after treatment, with the risk increasing with time. She concluded that, after 5 years, cancers that are seen in or around the radiation field are “more likely than not” due to the prior irradiation. This interpretation is in keeping with the results of the work from D’Amico who showed an increase in radiation-induced cancers from 7 years onwards. Moving forward, there is a potential to study alternative approaches to the use of docetaxel as well as the relevance of these findings with more modern radiotherapy.

Separate from the radiation-induced malignancy question raised by D’Amico is the suggest that there may be an overall survival benefit to the early use of docetaxel in men with high-grade prostate cancer with low-PSA based on a hypothesis that these tumors are less hormonally driven.

She concluded discussion of this paper by emphasizing that, as prostate cancer patients live longer, the importance and relevance of secondary cancers is increasing.

At this point, she transitioned to discussing the interim results of the aasur trial, presented by Dr. McBride. This study, performed as a single-arm phase II trial among patients with very-high risk non-metastatic disease, examines the principle of adding therapy (namely with apalutamide and abiraterone acetate) to radiotherapy and conventional ADT (leuprolide) but limiting the duration of therapy to 6 months, compared with the standard of 18-36 months for patients receiving conventional ADT alone. In addition to systemic intensification of care, the aasur trial also included radiotherapy dose intensification involving ultrahypofractionation with 7.5-8 Gray x 5 doses, an effect equivalent to administering 96-108 Gy in conventional fractionation. This approach is hypothesized to improve biochemical control and quality of life.

Dr. Vapiwala described the presented 3-year biochemical recurrence free survival (89.7%, 95% CI 81.0-99.3) as “promising”, also highlighting that there were statistically significant declines in urinary function as well as clinically meaningful declines in both sexual and hormonal domains (though these didn’t meet statistical significance as a result of small sample sizes).

These data highlight that initial intensification may actually be a means to de-intensify treatment: by giving a multi-drug approach early in the disease process, we may be able to reduce the duration of ADT exposure, reduce the duration and volume of radiotherapy (by ultrahypofractionation), and thus reduce the burden borne by patients. Ongoing follow-up of the aasur will help to delineate the utility of this approach. In particular, she emphasized that while aasur omitted elective nodal radiotherapy, other trials have demonstrated a benefit to this approach. Thus, there remains ongoing work to better ascertain the details of radiotherapy and systemic therapy in this approach.

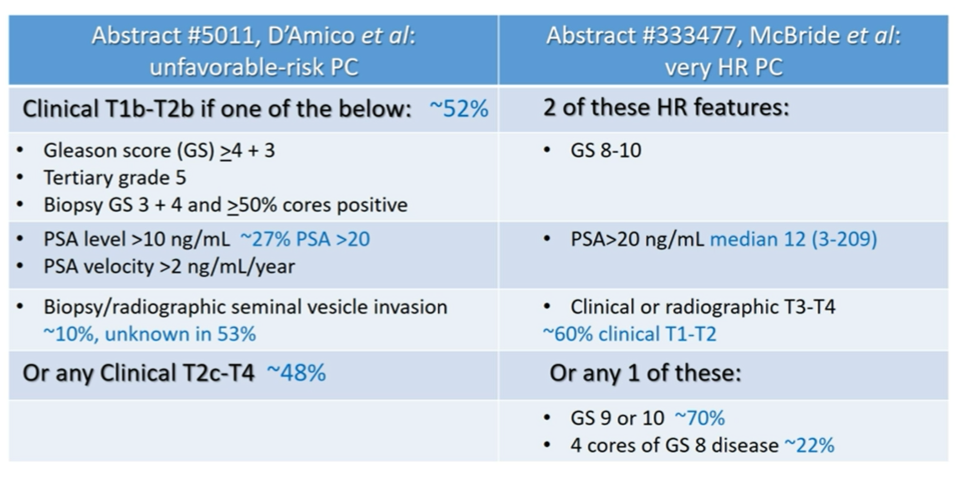

She emphasized the importance of considering the study populations as we consider how we may apply these data to our clinical practices. She emphasized that, in comparing the two, high-risk features were more common in the aasur trial.

She emphasized that, when compared to the NCCN definition of very-high risk disease (T3b-T4, primary Gleason pattern 5, 2 or 3 high-risk features, or >4 cores with Grade Group 4 or 5 disease), neither of these trials are particularly highly enriched with patients with the worst disease. She therefore suggested that systemic therapy intensification may have not been necessary for some of the enrolled patients.

As we move forward, she highlighted the critical importance of patient selection. There are always potential downsides to our best intentions, including the risk of recurrence, unknown long-term toxicity of newer agents, and the financial costs incurred in the name of expected (but not proven) better outcomes. As we move towards increasingly personalized care, molecular signatures and model derived data will be key to identify patients who need and benefit from intensification.

She emphasized that, when compared to the NCCN definition of very-high risk disease (T3b-T4, primary Gleason pattern 5, 2 or 3 high-risk features, or >4 cores with Grade Group 4 or 5 disease), neither of these trials are particularly highly enriched with patients with the worst disease. She therefore suggested that systemic therapy intensification may have not been necessary for some of the enrolled patients.

As we move forward, she highlighted the critical importance of patient selection. There are always potential downsides to our best intentions, including the risk of recurrence, unknown long-term toxicity of newer agents, and the financial costs incurred in the name of expected (but not proven) better outcomes. As we move towards increasingly personalized care, molecular signatures and model derived data will be key to identify patients who need and benefit from intensification.

Presented by: Neha Vapiwala, MD, FACR, Professor of Radiation Oncology, The University of Pennsylvania

Written by: Christopher J.D. Wallis, Urologic Oncology Fellow, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Contact: @WallisCJD on Twitter at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Virtual Annual Meeting #ASCO21, June, 4-8, 2021