She began by highlighting that many questions faced by medical oncologists treating genitourinary cancers:

#1. How long should a patient who is responding remain on therapy?

#2. How concerned should we be able to cumulative toxicity of long-term immunotherapy?

#3. What about if patients must discontinue immunotherapy due to adverse events?

#4. How often should we be monitoring patients?

She first sought to address the first of these questions, how long patients should continue on therapy. Highlighting data from both CheckMate025 (nivolumab vs everolimus) and CheckMate214 (ipilimumab/nivolumab vs sunitinib), she emphasized that these patients continued on (nivolumab) therapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. In contrast, in KEYNOTE-426 (pembrolizumab/axitinib vs sunitinib), pembrolizumab was limited to be administered for up to 35 cycles over two years. In advanced bladder cancer, the IMvigor210 trial utilized treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity, as did the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial of avelumab maintenance. However, in KEYNOTE-045 and KEYNOTE-052, treatment with pembrolizumab was limited to a maximum of 2 years.

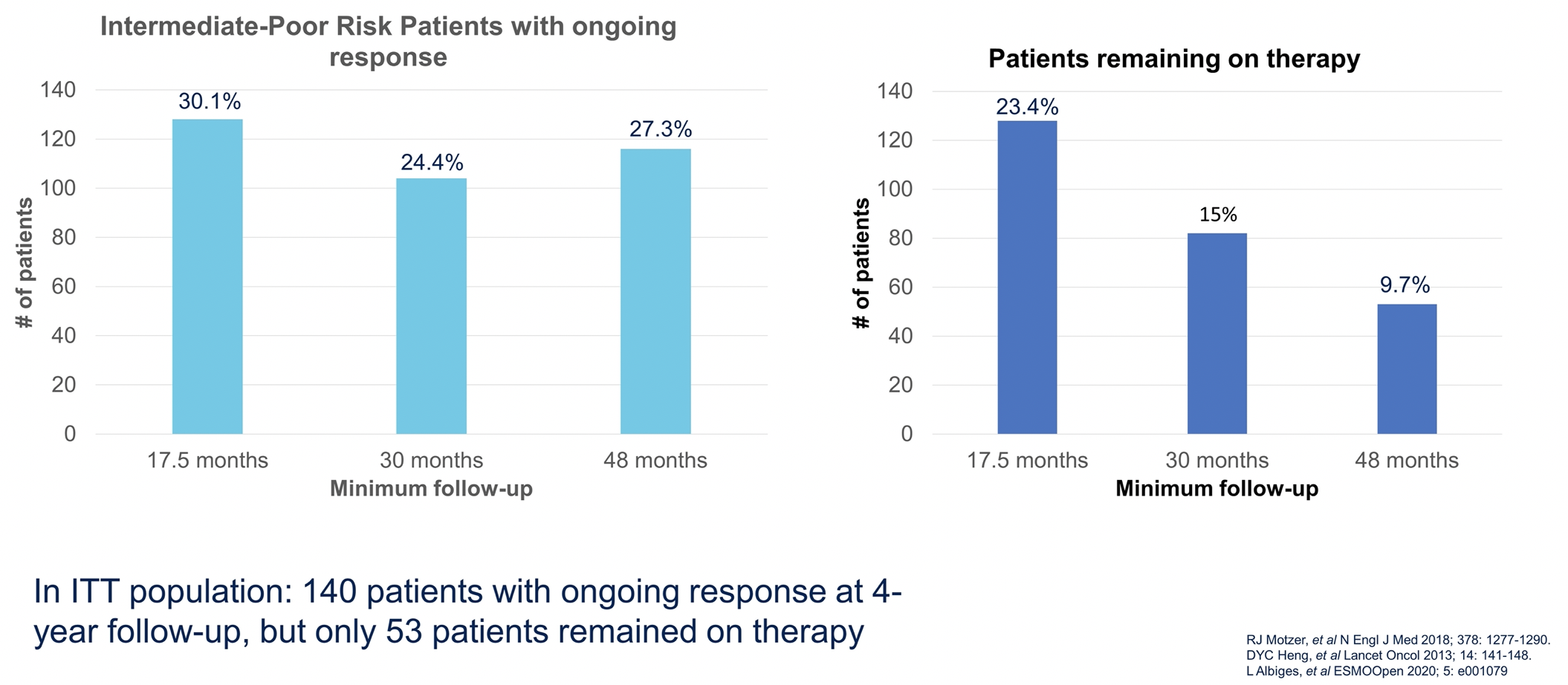

Despite the variations in design, Dr. Parikh suggested that these trials may offer data to inform the question of how long to continue therapy. Longitudinal data from the CheckMate214 demonstrates that the proportion of patients with an ongoing response changes only marginally from 17.5 months out to 48 months, while the proportion of patients remaining on therapy diminishes significantly.

This suggests that a proportion of patients will have a sustained, ongoing response despite stopping therapy.

In the bladder cancer space, she highlighted extended follow-up data from KEYNOTE-052 which showed that a portion of responders maintain their response despite having treatment cut-off at 2 years. Further, in the KEYNOTE-045 trial, while 46% of responders completed 2 years of therapy, 56% of patients had ongoing responses at a minimum follow-up of 2-years. Additionally, 10 patients discontinued therapy due to their complete response and maintained this response.

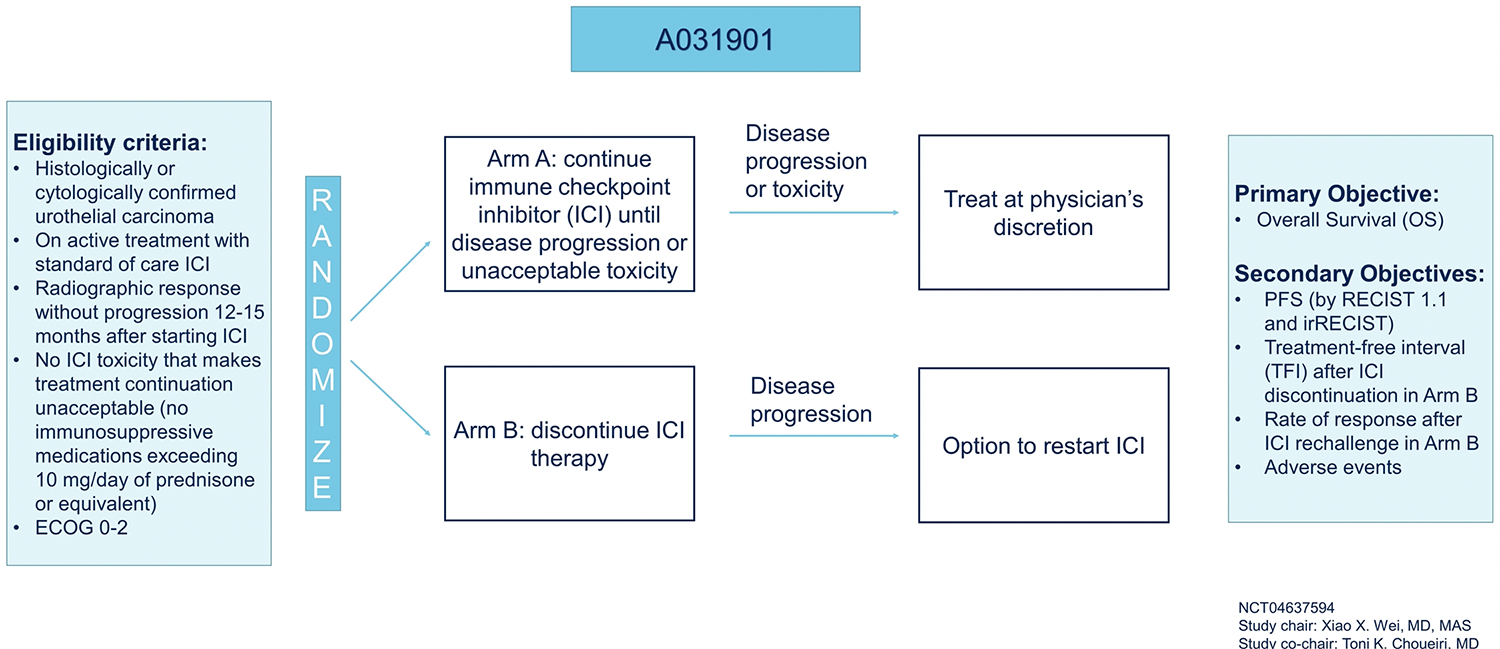

She then highlighted a trial which seeks to assess this exact question. This study will accrue patients with urothelial carcinoma who are treated with standard of care immune checkpoint inhibition who have radiographic response without progressive disease 12-15 months after starting immune checkpoint inhibition without significant checkpoint inhibitor attributable toxicity. Patients will then be randomized to continue immune checkpoint inhibitor until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity with subsequent treatment at the physician’s discretion or to stop immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy with the option to restart at the time of disease progression. This study is designed with a non-inferiority approach, assessing the primary endpoint of overall survival.

In addition to addressing the optimal duration of immunotherapy in this disease space, this study offers the potential to examine whether re-challenge with immunotherapy is efficacious. In the meantime, she suggested that more studies are needed. However, after two years it may be reasonable to consider discontinuation as some patients maintain responses. However, more pragmatic considerations are also relevant including the toxicity and burden of continuing therapy or, conversely, the anxiety regarding stopping therapy. Thus, she emphasized the importance of shared decision making.

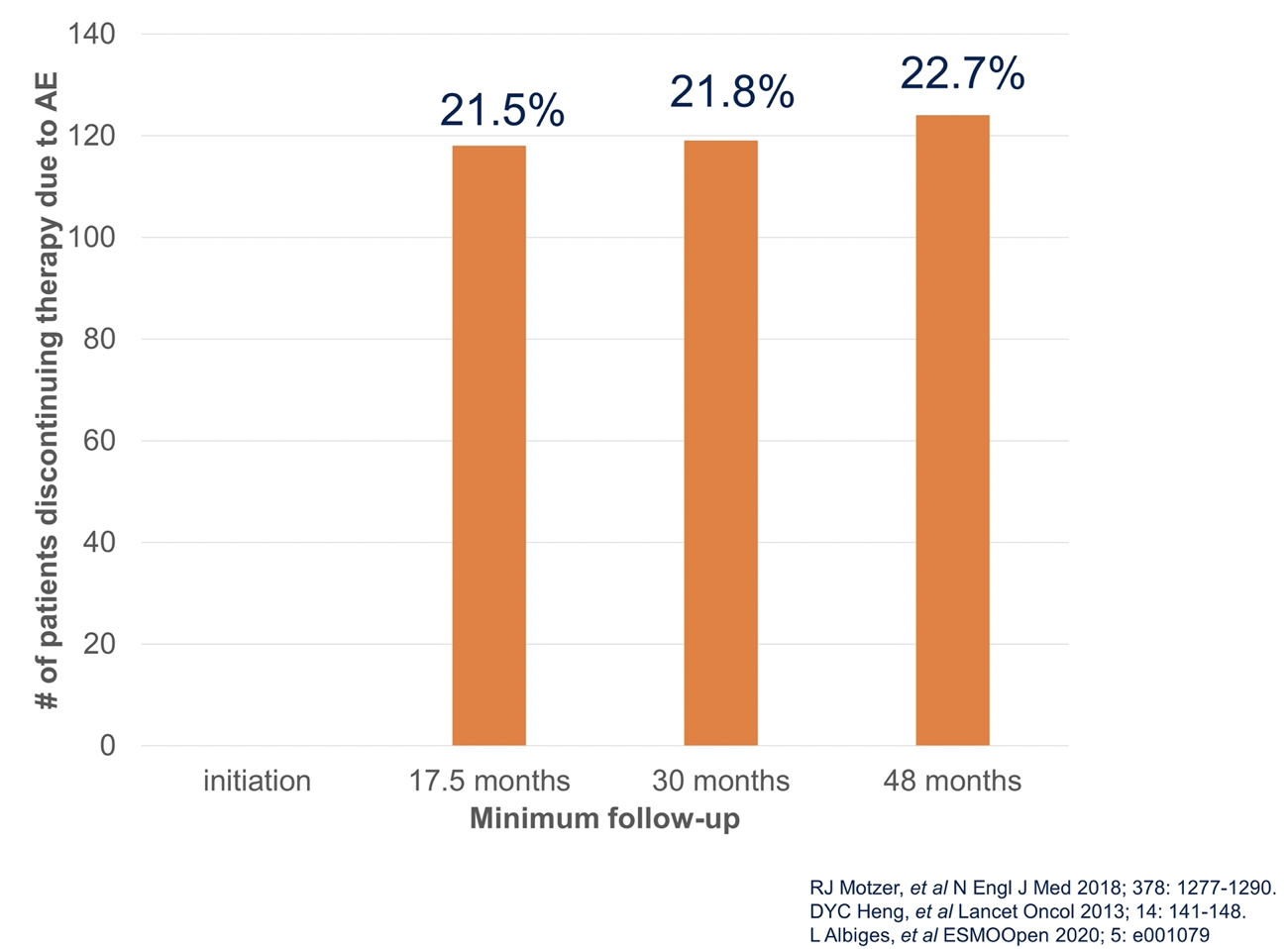

Moving to the second, “perhaps simpler”, question, Dr. Parikh considered the question of cumulative toxicity associated with long-term immunotherapy. Here, long-term follow-up data from CheckMate214 provides useful, demonstrating that over time, and especially after 18 months, new adverse events appear to plateau but not entirely resolve. Further, rates of treatment discontinuation associated with treatment-related toxicity were relatively unchanged over time, increasingly only marginally from 17.5 months of follow-up to 48 months of follow-up.

The data are somewhat less robust in urothelial carcinoma but the available data, including from KEYNOTE-052, suggest that rates of adverse events (and particularly grade 3 or greater adverse events) are not substantially more common among patients treated for more than 12 months than those who received 6 to 12 months of therapy. Overall, fewer than 10% of patients discontinued therapy due to toxicity. Thus, while toxicity can still occur, we needn’t be particularly concerned about cumulative immunotherapy toxicity.

Third, she considered the question of how to manage patients who must discontinue immunotherapy as a result of adverse events. Again, data from CheckMate214 can be informative. A post hoc analysis showed that patients who discontinued therapy due to adverse events had at least as good overall survival as those in the intention-to-treat population receiving combination immunotherapy. While this analysis doesn’t assess subsequent lines of therapy, it is reassuring. A small retrospective study of 19 patients stopping immunotherapy due to immune-related adverse events suggested that some patients can enjoy a treatment-free interval more than 6 months. Thus, she suggested that, based on limited data, we may consider a treatment-free period after the cessation of immunotherapy due to adverse events though patients should be monitored carefully during this time.

Finally, Dr. Parikh considered how often we should be monitoring patients. She presented practice considerations on the basis of NCCN guidelines for RCC which suggest clinical assessment and radiologic imaging every 6 to 16 weeks, though this should be altered due to the rate of disease change and the sites of active disease. In bladder cancer, NCCN guidelines recommend cystoscopy and imaging every 3 to 6 months for those who are not actively receiving systemic therapy though there is no specific guidance for patients undergoing active treatment.

As a result, she suggested a similar interval for patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors, wit the potential to lengthen the interval for those who are off treatment due to a sustained response and shorten the interval for those who are off treatment due to toxicity. This can be guided by patient’s clinical status, extent of disease, reliability of reporting symptoms, and prior response to therapy.

Presented by: Mamta Parikh, MD, MS, UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

Written by: Christopher J.D. Wallis, Urologic Oncology Fellow, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Contact: @WallisCJD on Twitter at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Virtual Annual Meeting #ASCO21, June, 4-8, 2021