Welcome to UroToday’s new Center of Excellence on Disparities: Social Determinants of Health. I am honored to serve as its Editor and excited to share new research and expert conversations with you. The World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define social determinants of health (SDOH) not as individual variables, but as the environments in which people are born, grow, learn, work, play, and age.1,2 Specific characteristics of these environments can either increase or reduce disparities in health, healthcare access, and quality of life among individuals, regions, and nations. This Center focuses on SDOH and healthcare disparities within urology, particularly genitourinary (GU) oncology. However, it is important to emphasize that SDOH affects all persons and all healthcare fields in a multitude of ways, and therefore, many topics covered by this Center will appeal to a broad audience. In this editorial, I outline the current status of GU research on SDOH and disparities, how experts are redefining SDOH and downstream effects in order to improve research and policy, and why it is crucial to engage medically underserved communities in these efforts.

For decades, GU oncology has remained in a state of awareness or observation about health disparities, acknowledging that they exist without proactively designing or testing solutions. For example, studies have correlated social and environmental variables such as race, location of residence, income, and other patient-level factors with disparities in GU cancer risk, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survival.3-7 From such studies, we know that kidney cancer-specific survival is significantly worse in rural versus urban areas, that survival in all types of GU malignancies is significantly lower among Black individuals compared with their White counterparts, and that undertreatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer is more common when patients are underinsured or have limited financial resources. Although such findings help generate awareness, their capacity to produce actionable next steps is limited. This is for two main reasons. First, the descriptive and reductionist approach of these studies does not reflect the real world, in which health outcomes are shaped not by individual traits, but by a complex interplay among many social, environmental, and biological factors.8,9 Second, an academic discourse that centers on patient-level explanations for disparities tends to put the onus for change on individuals, rather than prioritizing upstream, systems-level solutions that are more equitable and effective.10 For example, emails or “push notifications” encouraging cancer screening require recipients to be able to read and access smartphones, while systems-based and regional screening policies can potentially circumvent these barriers by targeting specific SDOH domains that are most relevant to a group or community.

Other oncology disciplines are moving beyond the limited individualistic approach to SDOH, which gives us a roadmap for research. For example, the ongoing WISDOM trial compares two approaches to breast cancer screening: 1) personalized imaging based on a composite of individual risk factors, and 2) conventional mammography. Primary outcomes are safety and morbidity, while secondary outcomes include a range of variables related to breast cancer detection, prevention, treatment, patient preferences for screening, decision regret, and anxiety.11 In GU oncology, we, too, can shift our research focus to explore multiple factors within relevant contexts. We can better identify novel measures and test systems-level interventions, such as screening based on individualized risk-factor assessments or matching clinical trial staff based on target demographics to improve recruitment.12

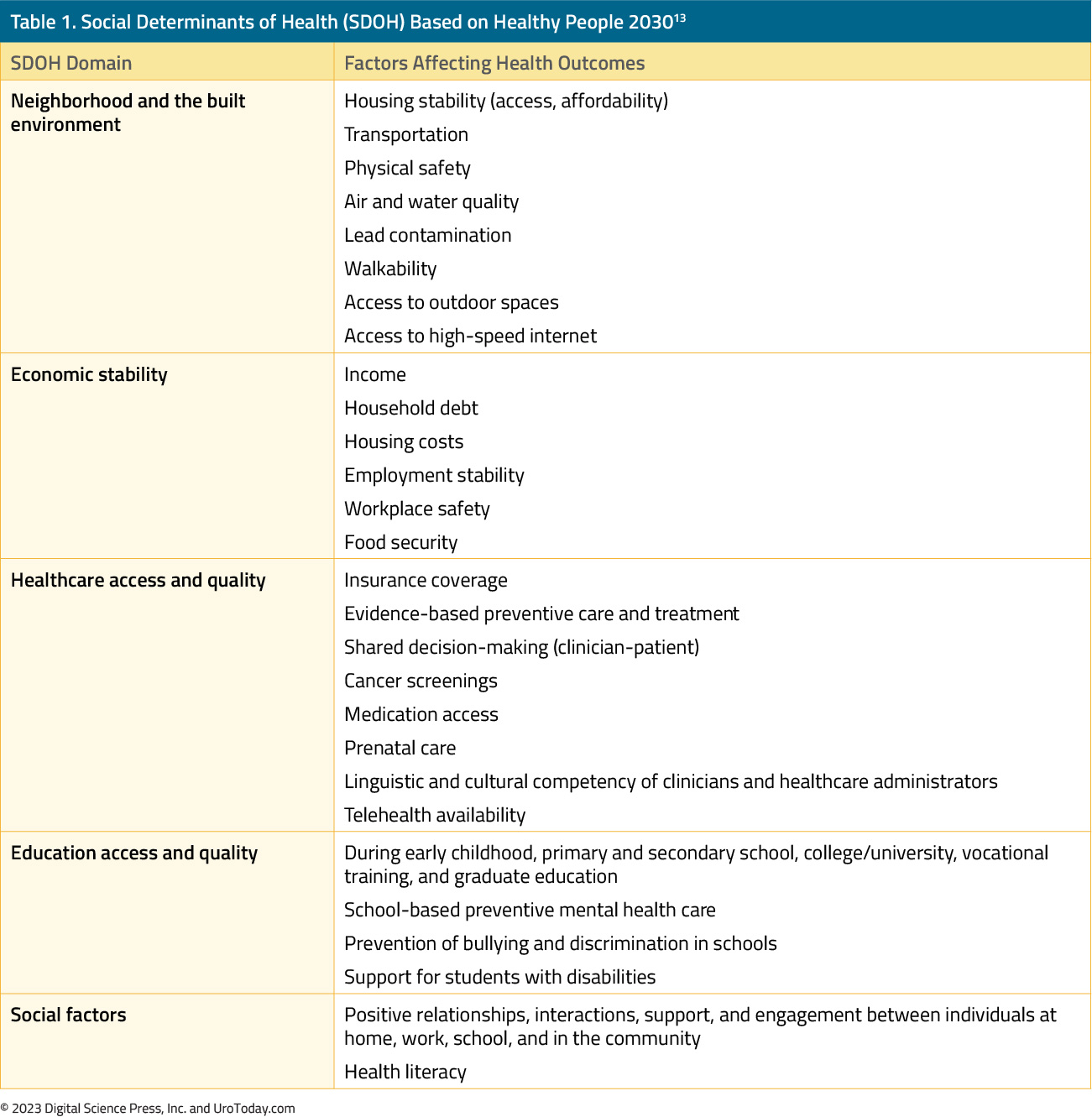

To do so, however, we first need to agree on a more rigorous and universal definition of SDOH. Healthy People (HP) 2030, a national, data-based initiative to improve health and well-being over the next decade, expands on the CDC and WHO definitions of SDOH by defining five specific domains: 1) neighborhood and the built environment, 2) economic stability, 3) healthcare access and quality, 4) educational access and quality, and 5) social and community contexts (Table 1).13 The CDC, WHO, and HP 2030 definitions all reflect the idea that SDOH is not something we have or can obtain and does not describe only a few people. They affect us all.14

Because of its specificity and comprehensiveness, HP 2030’s definition of SDOH can help guide researchers and policymakers toward questions and projects that more effectively identify actionable modifiers of health disparities and set targetable goals. However, these interventions are far more likely to succeed when developed collaboratively with the people they affect, an approach known as community-based participatory research (CBPR).15,16 CBPR is especially important when working with medically underserved communities—for example, to improve cancer care and clinical trial recruitment.17,18 Black patients remain vastly underrepresented in GU oncology trials, including those leading to regulatory approvals and guideline recommendations. When considering how to address this gap, we can again look to breast oncology, in which the WISDOM trial has substantially increased the enrollment of Black patients by proactively partnering with community groups and leaders.19 Effective community engagement is based on durable, non-transactional interactions, such as disseminating culturally competent information, sharing institutional resources with underserved communities, advocating for policies that support health equity, and building long-term research and service partnerships between communities and academic institutions.

In summary, disparities in GU oncology are significant, longstanding, and targetable. These disparities cannot be addressed by passively studying individual risk factors in isolation, as we have done for decades. This Center of Excellence aims to support scholarship and policy that shifts the SDOH paradigm to reflect how diverse factors interact within environments to affect health risks and outcomes. Redefining our approach to understanding SDOH can help us study inequities in disease risk and healthcare administration and delivery, evaluate existing attempts to overcome these disparities, and identify new measures that may further elucidate the context in which disparities exist. Only by creating partnerships outside our usual institutions and research bubbles can we advance our field. Social determinants of health naturally lend themselves to these approaches. I am excited to engage in this process with you.Written by: Samuel L Washington II, MD, MAS, Assistant Professor of Urology, Goldberg-Benioff Endowed Professorship in Cancer Biology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

References:

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 Accessed May 4, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health at CDC. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html. Accessed May 4, 2023.

- Howard JM, Nandy K, Woldu SL, et al. Demographic factors associated with non-guideline-based treatment of kidney cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(6):e2112813. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12813

- Gilbert SM, Pow-Sang JM, Xiao H. Geographical factors associated with health disparities in prostate cancer. Cancer Control 2016;23(4):401-408. doi: 10.1177/107327481602300411

- Sung JM, Martin JW, Jefferson FA, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in bladder cancer survival: analysis of the California Cancer Registry. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2019;17(5):e995-e1002. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2019.05.008

- Schafer EJ, Jemal A, Wiese D, et al. Disparities and trends in genitourinary cancer incidence and mortality in the USA. Eur Urol 2022:S0302-2838(22)02841-X. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.11.023

- Shah AA, Sun Z, Eom KY, et al. Treatment disparities in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Evidence from a large statewide cancer registry. Urol Oncol 2022;40(4):164.e17-164.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.12.004

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States; Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, et al, eds. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Jan 11. 3, The Root Causes of Health Inequity. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/ Accessed May 9, 2023.

- National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Disparities. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/disparities Accessed May 9, 2023.

- Adams J, Mytton O, White M, et al. Why are some population interventions for diet and obesity more equitable and effective than others? The role of individual agency. PLoS Med 2016;13(4):e1001990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990

- Esserman LJ; WISDOM Study and Athena Investigators. The WISDOM Study: breaking the deadlock in the breast cancer screening debate. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017;3:34. doi: 10.1038/s41523-017-0035-5

- Segre LS, Davila RC, Carter C, et al. Race/ethnicity matching boosts enrollment of black participants in clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2022;122:106936. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106936

- Healthy People 2030. What are social determinants of health? Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health Accessed May 4, 2023.

- Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q 2019;97(2):407-419. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community‐Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence: Summary. 2004 Aug. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 1998-2005. 99. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK11852/ Accessed May 4, 2023.

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Community-Based Participatory Research Program. Available at: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/extramural/community-based-participatory.html Accessed May 4, 2023.

- Ross L, Johnson J, Smallwood SW, et al; MAN UP Prostate Cancer Advocates. Using CBPR to extend prostate cancer education, counseling, and screening opportunities to urban-dwelling African-Americans. J Cancer Educ 2016;31(4):702-708. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0849-5

- Froelicher ES, Doolan D, Yerger VB, et al. Combining community participatory research with a randomized clinical trial: the Protecting the Hood Against Tobacco (PHAT) smoking cessation study. Heart Lung 2010;39(1):50-63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.06.004

- STAT. This clinical trial wanted to end breast cancer disparities. But first it needed to enroll Black women. Available at: https://www.statnews.com/2022/06/30/this-clinical-trial-wanted-to-end-breast-cancer-disparities-but-first-it-needed-to-enroll-black-women/ Accessed May 4, 2023