Published Date: March, 2016

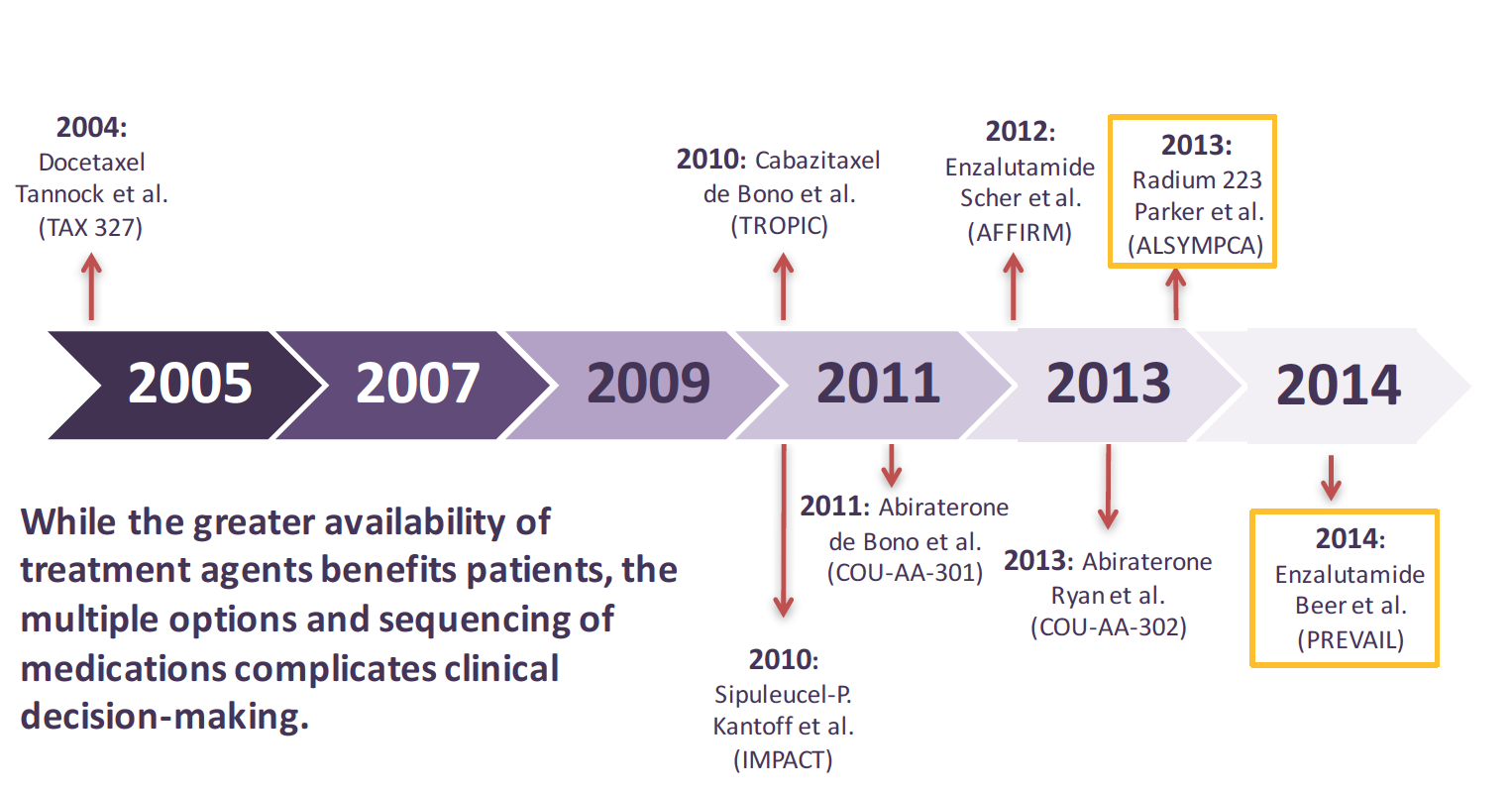

Before 2004, there was an unmet need for survival prolonging therapies in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Palliative therapeutic options were the standard of care. As a result, there was a pervasive nihilism regarding the therapeutic management of men with advanced prostate cancer, especially after they ceased responding to androgen suppressive therapy.In 2016, the situation is far different. In 2004, the first medication to improve survival rates in patients with CRPC was approved: chemotherapy with docetaxel, which clearly demonstrated an overall survival benefit compared with mitoxantrone therapy. Since 2010, five new therapies have also been added to the armamentarium, including the immunotherapy, sipuleucel-T; the novel hormonal antiandrogen therapies, abiraterone and enzalutamide; the chemotherapy, cabazitaxel and the radionuclide therapy, radium-223.

Some have now stated that we have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to the treatment of metastatic CRPC. Yet, there are ongoing and significant questions and concerns that remain for urologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists: How do we select the right therapy for the right patient at the right time, while being mindful of therapeutic effect, toxicities, and cost? How can we optimally combine and sequence these treatments? Fortunately, there are many phase II and phase III clinical trials attempting to fortify the evidenced based literature in order to answer these unmet needs..

First, let’s consider a review of the different medications approved and accessible for the treatment of metastatic CRPC.

Docetaxel was approved by the FDA as first-line therapy for advanced CRPC based on phase III clinical trials that showed that this taxane based chemotherapy extended survival by a median of 2.4- 2.9 months over mitoxantrone. [1] Numerous, subsequent clinical trials have studied the addition of other unique mechanism of action therapies to docetaxel—with the primary goal of improving docetaxel monotherapy survival rates. Unfortunately, none of these trials have succeeded, and thus we still lack data to support a combination docetaxel regimen for attaining a survival benefit..

Sipuleucel-T, an autologous cellular vaccine, was approved by the FDA in 2010 for metastatic CRPC on the strength of phase III clinical trial data that showed a median overall survival rate of 25.8 months for sipuleucel-T vs. 21.7 months versus the placebo arm. The trial demonstrated a 22% reduction in mortality risk, and it was the first immunotherapy to demonstrate a survival benefit for any solid tumor malignancy. Currently, the United States is the only country to have both regulatory and commercial approval for sipuleucel-T . Sipuleucel-T is manufactured by combining a fusion protein with the individual patient’s leukapharesis obtain dendritic cell population, and ultimately delivered by infusion 2 to 3 days later, whereby 3 doses, each given as 60-minute IV infusions, 2 weeks apart, which completes the course of therapy. The safety and tolerability for administration of sipuleucel-T is well documented, and essentially, very well tolerated; e infusion reactions may occur, which can cause fever, myalgia, and hypotension. [2]

The novel hormonal therapy, abiraterone, an oral medication, is approved for the treatment of metastatic CRPC in combination with prednisone. In phase III trials it increased overall survival a median of 3.9 months compared versus placebo when administered post-docetaxel therapy. In chemotherapy-naïve patients, the medication improved survival by a median of 4.4 months compared with placebo. [3, 4] Abiraterone should be used with caution in patients with a history of significant congestive heart failure. The effects of abiraterone exposure may increase up to 10-fold when taken with meals, thus patients are instructed to ingest the medication in a non-fed state. Of note, recent trials are investigating its use with once daily 5mg prednisone and, even no prednisone use, for some patients. Because it can affect CYP enzymes, it’s important to check drug-drug interactions. Before and during treatment, it’s important to monitor blood pressure, signs of fluid retention, as well as electrolyte and hepatic function stability. If liver function tests are abnormal, drug dosing can be modified, interrupted with ongoing monitoring to allow for optimal dosing.

Enzalutamide, another novel hormonal CRPC agent, is also administered as an oral agent, but without a prednisone requirement. It was approved based upon randomized controlled trials that showed it extended survival a median of 4.8 months compared with placebo in patients who had previously received docetaxel. In a final phase III analysis, it also extended survival a median of 3.9 months in chemotherapy-naïve patients when compared with placebo. Of note, unique adverse events of interest, albeit in a very low percentage of patients, may precipitate seizures and fatigue. Similarly, enzalutamide is predominantly metabolized by the liver, and clinicians should be aware of certain listed drug-drug interactions. The current capsules may be ingested with or without food. [5, 6]

Cabazitaxel is another taxane based chemotherapy drug administered in combination with prednisone in patients with metastatic CRPC previously treated with docetaxel, whom have demonstrated progression. In clinical trials, cabazitaxel increased median survival by 2.4 months when compared with mitoxantrone/P. Similar to docetaxel, it is administered as a 1-hour infusion every 3 weeks with concomitant steroid use. As with other taxane based therapy, the primary safety considerations are myelosuppression. Both renal and hepatic impairment can provide further obstacle to the use of cabazitaxel. Many have noted the advantage of its use, compared to docetaxel, in observing less neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue. [7]

The most recent CRPC approved therapy, radium-223, is indicated in the treatment of patients with metastatic CRPC with symptomatic bone metastases, but no known visceral metastatic disease. In the phase III ALSYMPCA clinical trial, it extended survival rates a median of 3.6 months for a trial population inclusive of both pre- and post-docetaxel CRPC patients. The ALSYMPCA trial enrolled patients with progressive CRPC with 2 or more bone metastases. A total of 921 patients were randomly assigned to receive radium-223 or a saline placebo infusion every 4 weeks for 6 cycles. The primary endpoint indicated that radium-223 treatment resulted in a 30% reduction in mortality. The medication also significantly prolonged median time to first symptomatic skeletal event. [8]

Additionally, radium-223 had a beneficial effect on delaying pain and also preserved health-related quality of life. The median time to initial opioid use was significantly longer for radium-223 than placebo (HR =.62), for instance. A higher percentage of patients in the radium-223 group than those in the placebo group had a clinically meaningful improvement in health-related quality of life as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate score (an increase of 10 or more points above baseline during the drug administration period). Of the patients in the radium-223 group, 25% had significantly improved quality of life vs. 16% of those in the placebo group (p =.02).

In a small percentage of patients, radium-223 can cause grade 3-4 anemia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. Blood counts should be obtained prior to treatment initiation and before every dose in patients receiving radium-223, and those with compromised bone marrow reserve should be closely monitored.

Although there is a paucity of comparative data on these medications, guidelines by the American Urological Association (AUA) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provide us with guidance on which therapies are supported by level 1 evidence in sub types of patients with CRPC. Treatment of non-metastatic or M0 CRPC is clearly an unmet need, however, as none of the abovementioned CRPC therapies are approved for use in this setting. The best choices in these patients, therefore, are second-line hormonal therapies after an initial hormonal therapy failure, or preferably, a clinical trial. Patients should also be subject to close observation and follow-up with imaging when PSA levels increase 2 ng/mL or more, when PSA rises to 5 ng/mL and at every doubling of PSA level thereafter (based on PSA testing every 3 months). [9].

The second-line hormonal therapies in these patients include first-generation antiandrogens such as flutamide, bicalutamide and nilutamide,, first generation androgen synthesis inhibitors (ketoconazole plus a steroid), or estrogens.

The guidelines suggest that patients with metastatic asymptomatic CRPC or those with minimal symptoms can benefit from abiraterone, enzalutamide and sipuleucel-T. Sipuleucel-T is ideally suited to be the first option in these patients, because their immune systems may be less suppressed than those of patients with more extensive disease and tumor burden and thus may have a more robust response to the vaccine. In patients with metastatic CRPC with symptoms who are chemotherapy-naïve, docetaxel, radium-223, abiraterone and enzalutamide are also options. In patients who have already received docetaxel, all of these agents can be used in addition to sipuleucel-T and cabazitaxel.

The novel hormonal therapies, abiraterone and enzalutamide are particularly beneficial in patients with metastatic CRPC who are naïve to any therapy. Research and clinical experience indicate that many patients will experience a substantial decline in PSA with these agents, while perhaps 8% to 12% of those treated demonstrate primary resistance. Sensitivity to these medications may vary from patient to patient, and patients who are resistant to one agent may respond to the second, but usually for a limited duration.

PSA responses to the novel hormonal therapies can also vary depending on mutational predominance. Of note, patients who have the AR-V7 biomarker are unlikely to respond to either enzalutamide or abiraterone. However, patients with AR-V7 variants do respond to other therapies. Studies show that upwards of 50% of patients with CRPC who have this variant will respond to docetaxel or cabazitaxel.

Radium-223, with its unique proposed mechanism of action, enhancing apoptotic effect at bone mineralization sites, suggests its suitability fro combination therapy with the novel hormonal agents, specifically CRPC pts with bone metastases. It can be administered in patients with a wide spectrum of bone symptomology, and whether or not the patient has had previous chemotherapy. Unlike prior radiopharmaceuticals, it is not prescribed primarily for pain palliation, instead, should be prescribed for its overall survival benefits. Radium-223 can be given before or after chemotherapy, but not concomitantly with chemotherapy. [10]

As noted earlier, there is a paucity of data on combining or sequencing these approved CRPC agents, hence, treatment decisions in the clinic often depend on drug availability, performance status, age, patient comorbidities and the patient's response and resistance to prior therapies. The burden and location of disease, the pace of progression of the patient’s cancer, whether the progression is systemic or focal, and patient preference also play a part in the decision-making process. It’s essential to have a broad based and thoughtful discussion with the patient and caregivers about the advantages and disadvantages of all therapies.

Fortunately, there are many ongoing clinical trials are now testing the combination and sequencing of the new therapies for metastatic CRPC. Within the next 2 years, we should have answers to the questions regarding how best to sequence and combine these approved agents. Currently,, there may exist concerns about whether combining these agents could lead to undue clinical and financial toxicities.

As noted in the proceedings of the St. Gallen Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference in 2015, we are still awaiting the results of large-scale prospective studies that can inform us how to optimally sequence the new agents we have to treat metastatic CRPC. Identifying predictive markers for selecting patients for these therapies is also an ongoing research area of interest will assuredly assist our goal of achieving precision medicine. [11] Discovering predictive markers for response to our current therapies is especially crucial since there exists increasing evidence that some castration-resistant phenotypes are more responsive to hormonal strategies, while others may be more effectively treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Effective combination therapies may also improve outcomes of both progression and survival, while hopefully preventing toxicities and their attendant use of inpatient and emergency department services. [12]

Written By Neal Shore, MD

References:

1. Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502-1512.

2. Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T Immunotherapy for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer for the IMPACT Study Investigators.

N Engl J Med 2010;363:411-422.

3. de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995-2005.

4. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2): 152-60.

5. Steer HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367(13): 1187-97.

6. Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(5):424-33.

7. de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomized open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747): 1147-54.

8. Hoskins P, Sartor O, O’Sullivan JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of radium-223 dichloride in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and symptomatic bone metastases, with or without previous docetaxel use: a prespecified subgroup analysis from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 ALSYMPCA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15(12): 1397-406.

9. Crawford ED, Stone NN, Yu EY, et al. Challenges and recommendations for early identification of metastatic disease in prostate cancer. Urology. 2014;83(3):664-9.

10. Shore ND, Radium-223 dichloride for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the urologist's perspective. Urology. 2015 Apr;85(4):717-24.

11. Gillessen S, Olin A, Attard G, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: recommendations of the St Gallen Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) 2015. Ann Oncol. 2015 Aug;26(8):1589-604.

12. Saad, F. Carles, J. Gillessen, S. et al. Radium-223 in an international early access program (EAP): Effects of concomitant medication on overall survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRCP) patients. J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 5034).