Structural racism, fueled by an ideology of the dominant culture, creates racialized structures and systems in which the inequitable resource and risk distribution (re)produces inequities in outcomes across systems. For example, minoritized and socioeconomically vulnerable populations often reside far from large academic centers and seek care at lower-resource facilities. Thus, to reduce inequities in outcomes of cancer care, it is equally important to understand where health disparity populations seek care and to evaluate whether care at these facilities contributes to inequities in receiving treatment. While previous work by our team and others explored this for various settings and conditions, the intersectionality between facilities that predominantly serve minoritized and socioeconomically vulnerable populations - making up health disparity populations - has not been explored yet.

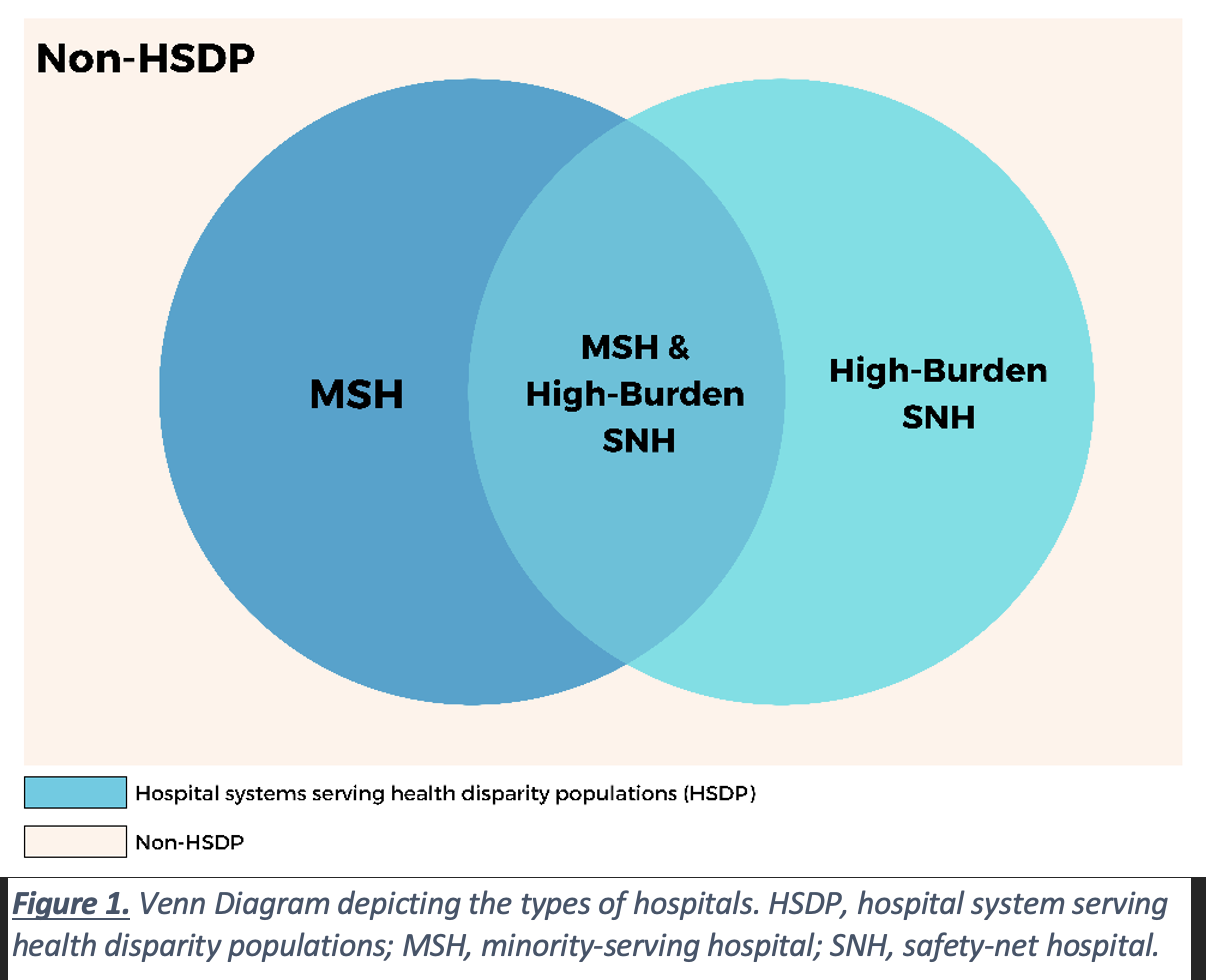

In our study, we investigated how prostate cancer care and outcomes differ between hospital systems serving health disparity populations (HSDPs) versus non-HSDPs. We have coined the term HSDP to capture the breadth of care received by health disparity populations. As illustrated in Figure 1, HSDP facilities are either (1) minority-serving hospitals only (MSH), (2) high-burden safety-net hospitals only (SNH), or (3) facilities that are both MSH and high-burden SNH. Previous studies have investigated care at MSH-only or SNH-only facilities. Nevertheless, examining care at HSDPs grants researchers and policymakers a more holistic perspective on the characteristics of hospitals that might be driving inequities in outcomes.

In this study published in Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, we used the National Cancer Database to compare the receipt of guideline-concordant definitive treatment for prostate cancer, time to treatment initiation, and overall survival between HSDPs and non-HSDPs.1 We included 968 non-HSDPs (72.2%) and 373 HSDPs (27.8%) facilities. We found that care at HSDPs was associated with lower definitive treatment, time to treatment initiation, and worse survival among men with prostate cancer, but not when definitive treatment was received. We also found that disparities in outcomes were primarily driven by facilities that are both MSH and high-burden SNH, followed by high-burden SNH-only facilities, and finally by MSH-only facilities. Additionally, non-Hispanic Black men are more likely to be treated at HSDPs, and they had worse outcomes than their White counterparts at these same institutions.

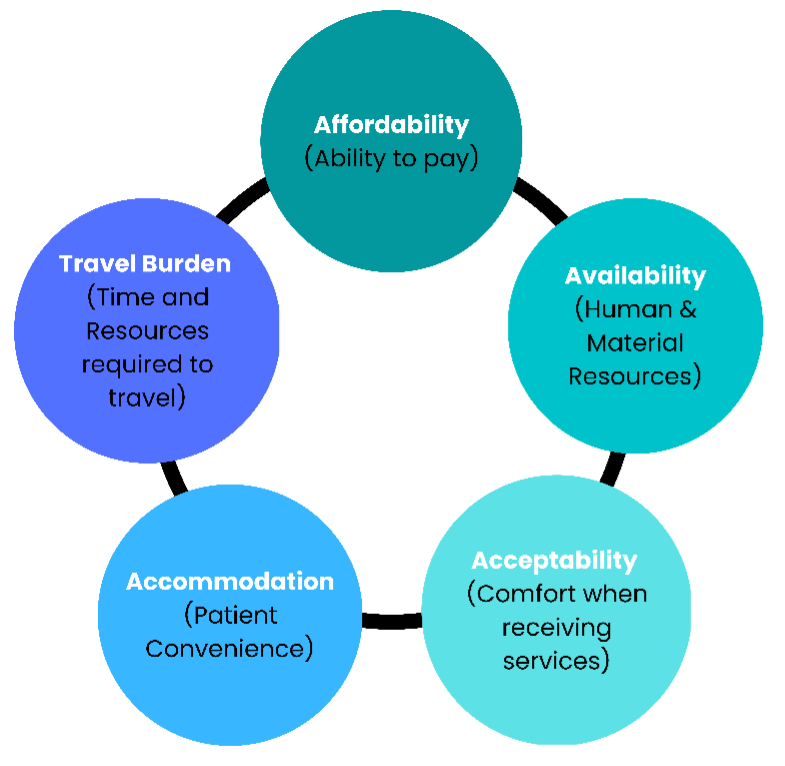

From this research and previous work we have done, it is clear that Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act does not address all the needs at MSHs,2 but rather efficient interventions to improve health care for health disparity populations may benefit from understanding differences in hospitals where these populations tend to receive care. Nevertheless, quantifying differences between HSDPs and non-HSDPs tells only part of the story. On the other hand, qualitative data collection can facilitate a detailed exploration of organizational, cultural, and systems-based factors associated with success at different hospitals. With our American Cancer Society-funded grant, we are conducting case studies at hospital systems across Massachusetts to understand how facilities handle disparities in prostate cancer care.3 By conducting multi-level interviews, we aim to understand the barriers and facilitators in accessing care among health disparity populations across hospital systems, but more importantly, among facilities that have historically served these populations. Preliminary analyses demonstrate that the success of these facilities lies in their comprehensive approach to facilitating care for health disparity populations. Despite the facilities’ lower resources, they have developed processes that address the five dimensions of access to care (Figure 2).4

These facilities have recognized that to reduce racial disparities in access to prostate cancer care, they had to channel resources to accommodate care (e.g., provision of patient navigators), provide culturally tailored services, diversify the workforce to increase the acceptability of care, and mobilize social workers and community health care workers that can work around insurance coverage as well as reducing travel burden to and from facilities. While our findings might be just the tip of the iceberg, these qualitative case studies, considering structural racism and how it affects organizational practices, will allow us to gain a nuanced understanding of system-level factors and how they intersect with access to care. Insight into these factors will provide the basis for our understanding of the most effective cross-cutting hospital practices needed to provide high-quality access to care within HSDPs.

While individual behaviors certainly influence disparities, our focus in this work on hospitals as the unit of analysis represents a novel approach to studying ways to reduce cancer disparities. Improving care at HSDPs represents a powerful tool with which to tackle cancer inequities. That said, further research should investigate whether the findings apply to other urological and non-urological cancers.

Written by:

- Muhieddine Labban, MD, Division of Urological Surgery and Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA,

- David-Dan Nguyen, MDCM, MPH, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- Christopher J.D. Wallis, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor in the Division of Urology at the University of Toronto

- Alexander P. Cole, MD, Center for Surgery and Public Health, Division of Urological Surgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

- Quoc-Dien Trinh, MD, MBA, Division of Urology and Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

- Nguyen DD, Labban M, Briggs L, et al. Access to definitive treatment and survival for intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer at hospital systems serving health disparity populations. Urol Oncol. 2023.

- Nguyen DD, Paciotti M, Marchese M, et al. Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Receipt of Definitive Treatment and Time to Treatment Initiation by Racial and Ethnic Minorities and at Minority-Serving Hospitals: A Patient-Level and Facility-Level Analysis of Breast, Colon, Lung, and Prostate Cancer. JCO Oncology Practice. 2021;17(5):e654-e665.

- American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society and Pfizer Launch Community Grants Focused on Reducing Prostate Cancer Disparities Among Black Men. American Cancer Society News Room Web site.

- Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127-140.