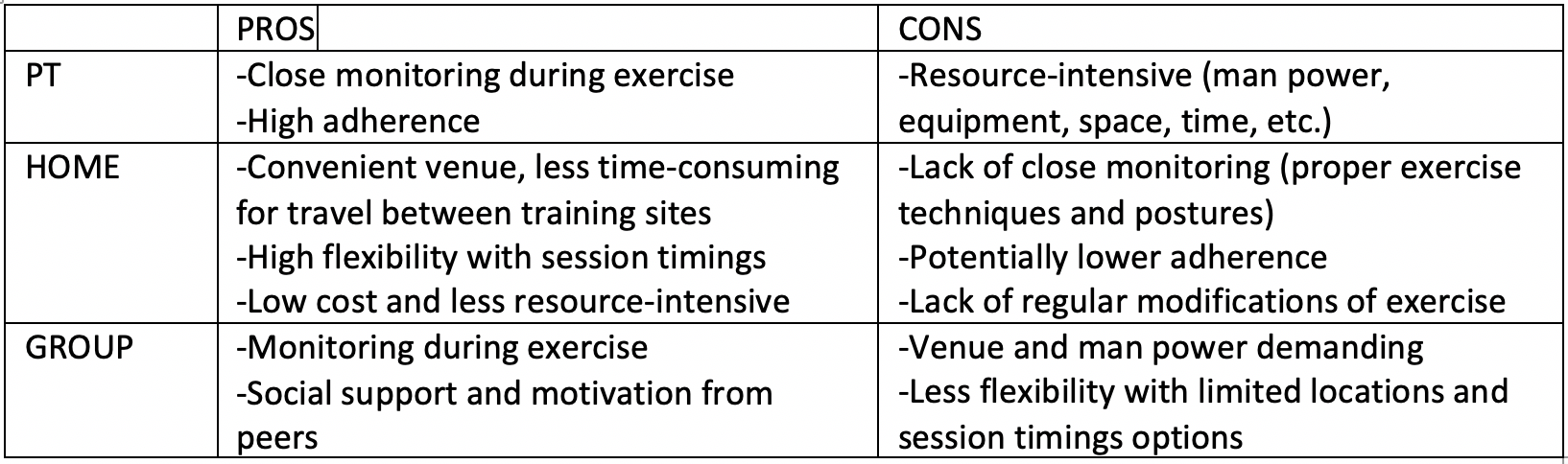

However, few studies have directly compared exercise delivery methods such as 1:1 personal training (PT), which is the usual gold standard, with less resource-intensive methods like home-based (HOME) and supervised group-based (GROUP) exercise programs for men with prostate cancer. It is essential for us to explore the efficacy and feasibility of these three methods due to their distinct benefits and drawbacks as summarized in the following table:

Importantly, no study has directly compared the 3 main exercise delivery methods. Our study was carried out to further investigate the efficacy and feasibility of the three delivery methods on improving quality of life (QOL) and physical fitness between PT and HOME/GROUP. Fifty-nine consented patients were randomized 1:1:1 to PT, HOME and GROUP arms to complete moderate intensity aerobically, resistance and flexibility exercises 4-5 times per week for six months while wearing a heart rate (HR) monitor. Outcome assessments on cancer-related fatigue and health-related QOL were completed using three measures – The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, Prostate, and Fatigue (FACT-G, FACT-P, and FACT-F. respectively). Also, three physical fitness measures were completed - grip strength, volitional peak oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) and one-minute sit-to-stand test, at baseline and every 3 months for a year.

Results of the above 6 measures show that PT gives a greater improvement on fatigue and physical fitness than HOME and GROUP, with HOME having the least improvement from baseline to 6 months. Overall, two of six outcomes (FACT-P and FACT-G) have a >20% probability of GROUP being inferior to PT. In contrast, four of six outcomes (FACT-P, FACT-G, grip strength, and VO2 peak) for HOME had a >20% probability of being inferior to PT. FACT-P and FACT-G measure comparisons with PT are found to be consistent for both HOME and GROUP.

Even with a low adherence rate of <50% and only 2-4 outcomes out of 6 to have significant differences among the three arms, this does not give us definitive results and does not reflect the whole picture without taking patients’ experience into account. The retention rate was 76.3%, and overall intervention satisfaction was rated at 4 or above (‘Very Satisfied’) on a 5-point Likert Scale by 88% of participants. Patients were impressed by how the program improved their situations as a “life changer” and how they “can lift more weight as the weeks go by” and were “no longer tired throughout the day”. The reason why they joined this program was that prior to the study, many men were “feeling sorry for [themselves], totally unmotivated, and physically unwell” and they “did not know what to do with [themselves]”. Many patients felt helpless and unable to contribute to the decision-making of treatments besides doing what the doctors told them to. During the program, they were “feeling better physically and mentally” and were “starting to get [their] muscle mass back, each and every week there was an improvement”. They also noticed that their “outlook on life has improved dramatically” and the program “taught [them] that [they] can take more control of [their] health”. They “recommend joining to meet other men going through similar experiences and together, improving wellbeing”.

Recruitment rate was 25.4% with the most common reasons for declining participation being lack of interest and living too far. This can be addressed by providing better incentives such as giving out equipment post-trial and longer voluntary follow up. We could potentially make the study available in more locations and provide a wider range of GROUP session timings to accommodate more interested participants and advance recruitment. The adherence rate, as reflected by accelerometers, of 50% in HOME, 42% in PT and 22% in GROUP was lower than expected. Our low adherence rate could also be affected by the fact that we excluded patients who were already participating in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), so all the patients who took part in this study were just starting or re-starting in a regular exercise program which would require more effort and time, especially following a diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Low adherence rates can be improved by providing more online interactive exercise tips and regular monitoring using wearable devices on the side, especially for HOME. Moreover, there is a potential of narrowing the age range of eligibility in future studies to minimize its variance on physical fitness outcomes. On the other hand, a field to further explore would be the patients’ mental health: does it improve while doing more exercise? Another focus can be placed on comparing the effectiveness of having other patients with similar experiences by their side as motivation in GROUP from doing it solo in HOME. There are many more factors to be looked at and direct comparison could be done between HOME and GROUP to shed some light on the cost-effectiveness between methods. Our Phase III exercise study program is on track to add a vital new perspective of cost-effectiveness between methods by having a larger sample size for more extensive and thorough evaluation 5.

Written by: Ko, Tina Lok Sun; Iqbal, Amna; O’Neill, Meagan; and Alibhai, Shabbir M.H., Department of Medicine and the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, The University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario.

References:

1. Saylor, P. J., & Smith, M. R. (2010). Adverse Effects of Androgen Deprivation Therapy: Defining the Problem and Promoting Health Among Men with Prostate Cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 8(2), 211-223. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0014

2. Winters-Stone, K. M., Moe, E., Graff, J. N., Dieckmann, N. F., Stoyles, S., Borsch, C., . . . Beer, T. M. (2017). Falls and Frailty in Prostate Cancer Survivors: Current, Past, and Never Users of Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(7), 1414-1419. doi:10.1111/jgs.14795

3. Bourke, L., Smith, D., Steed, L., Hooper, R., Carter, A., Catto, J., . . . Rosario, D. J. (2016). Exercise for Men with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European Urology, 69(4), 693-703. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.047

4. Mustian, K. M., Alfano, C. M., Heckler, C., Kleckner, A. S., Kleckner, I. R., Leach, C. R., . . . Miller, S. M. (2017). Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue. JAMA Oncology, 3(7), 961. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914

5. Alibhai, S. M., Ritvo, P., Mina, D. S., Sabiston, C., Krahn, M., Tomlinson, G., . . . Culos-Reed, S. N. (2018). Protocol for a phase III RCT and economic analysis of two exercise delivery methods in men with PC on ADT. BMC Cancer, 18(1). doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4937-x

Read the Abstract