High-grade nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer is still a challenge for urologists. Its current treatment is transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) followed by intravesical instillations of BCG.

This challenge is due to several reasons:

- The response to these treatments in high-risk NMIBC is limited and up to 40 % of patients will present disease recurrence. An additional around 15 % of them will progress to muscle-invasive disease.

- Recently, there have been BCG shortages due to different reasons that have led to the mistreatment of several patients, not completing full schedules of BCG.

- When a patient has a recurrence after being treated with BCG, the only treatment available until January 2020 was radical cystectomy.

Recent studies of checkpoint inhibitors in other malignancies and in more advanced stages of urothelial carcinomas have put the focus on these molecules to treat patients with high-risk NMIBC.

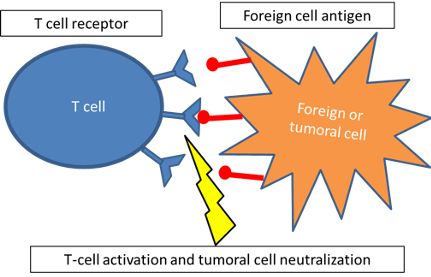

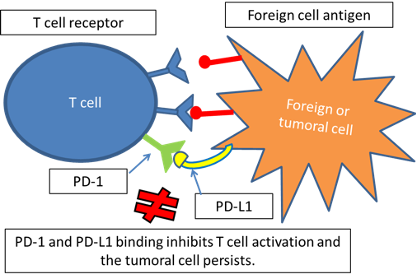

The main role of immune checkpoints is to protect from self-damage when immunity attacks pathogens (Figure 1). T-cells have receptors such as PD-1 and CTLA-4. When these receptors bind to their ligands (expressed by self-cells) such as PD-L1, T-cells are downregulated and maintain tolerance to these tissues. It has been stated that a frequent reason why tumors can progress and spread is that they develop ligands that can bind to PD-1 or CTLA-4. Therefore the T-cell is inhibited and the tumoral tissue can grow (Figure 2).

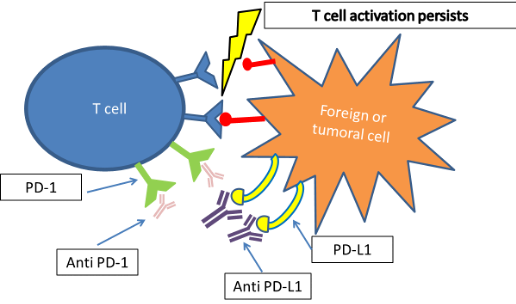

Checkpoint inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies that bind to PD-1 or to PD-L1 and block the binding with T-cells, keeping them activated so they can attack tumoral tissue (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Role of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Figure 2. Growth of tumoral tissue

Figure 3. Persistence of T-cell activation

But, what is really the relationship between BCG and the PD/PD-L1 pathway? Well, several studies have demonstrated that PD-L1 expression is enhanced in tumor tissue after BCG failure. A recent study in mice also reported a better oncologic response after treatment with checkpoint inhibitors combined with BCG than with any agent alone.

Thus, it seems logical to find out if these checkpoint inhibitors are an option in patients with high-grade NMIBC. There are two main groups of study: patients who are BCG unresponsive and patients who have never received BCG (BCG-naïve).

The first group is bigger, as the only chance for these patients until recently was radical cystectomy. Currently, there are 15 ongoing clinical trials. There are promising results in the use of pembrolizumab, which was approved by the FDA in January 2020. The results are similar for atezolizumab, but this drug is still not approved for this use.

In the treatment of the second group, there are currently five ongoing clinical trials. One of them is BladderGATE, the above mentioned with a translational profile. Now that it is proved that checkpoint inhibitors are effective in the treatment of patients with BCG unresponsive NMIBC, we should, on one hand, try to enhance the response to BCG by combining these drugs with BCG in patients who have never been treated, and, on the other hand, perform molecular studies to identify which subpopulation of patients may respond to these monoclonal antibodies.

It seems important to keep investigating in this field and keep the urologic community informed about these new treatment alternatives that are slowly rising and will have soon wider indications.

Written by: Carmen Gómez del Cañizo, MD, PhD, Twitter: @cgdelcanizo, and Félix Guerrero Ramos, MD, PhD, FEBU, Twitter: @DrFelixGuerrero, Department of Urologic Oncology, Urology Unit, University Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain

Read the Abstract