The Ongoing Evolution of a Field: Advances In First Line Therapy For Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Introduction

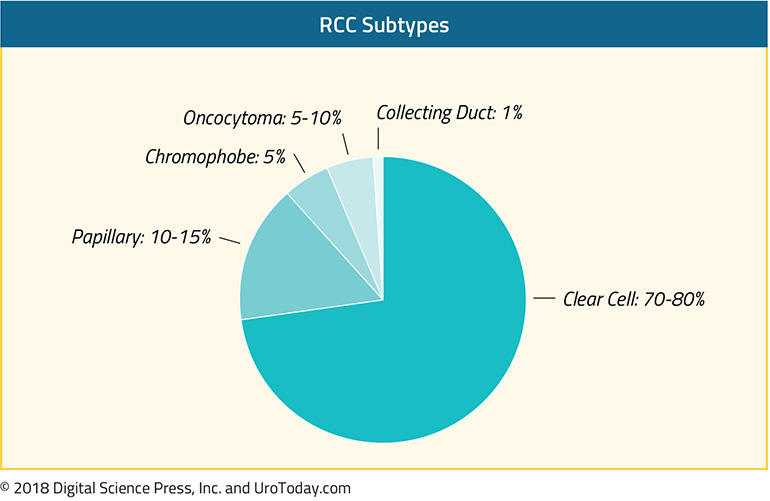

Cancers of the kidney and renal pelvis (when considered in aggregate despite different histology) represent the 6th most common newly diagnosed tumors in men and 8th most common in women in the United States in 20201, representing an estimated 73,750 new diagnoses and 14,830 deaths. The vast majority of these cancers will be renal parenchymal tumors with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) comprising the large majority with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most common histologic subtype of renal cell carcinoma. Due to its prevalence, the vast majority of advances in systemic therapies for RCC have been made for patients with ccRCC. However, there have been important recent advances in treatment for patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas (nccRCC) as well in recent years.

Despite ongoing stage migration as a result of widespread use of axial abdominal imaging for non-specific abdominal complaints2, a large proportion (up to 35%) of patients present with advanced disease, including metastases3. Historically, metastatic RCC has been early uniformly fatal, with 10-year survival rates less than 5%4. However, there has been transformational change in this disease space over the past fifteen years and, with newer immunotherapy-based approaches, the potential for long-term cure is something that may be considered. Certainly, a significantly longer natural history is feasible given available therapeutic options.

The Historical and Near Past

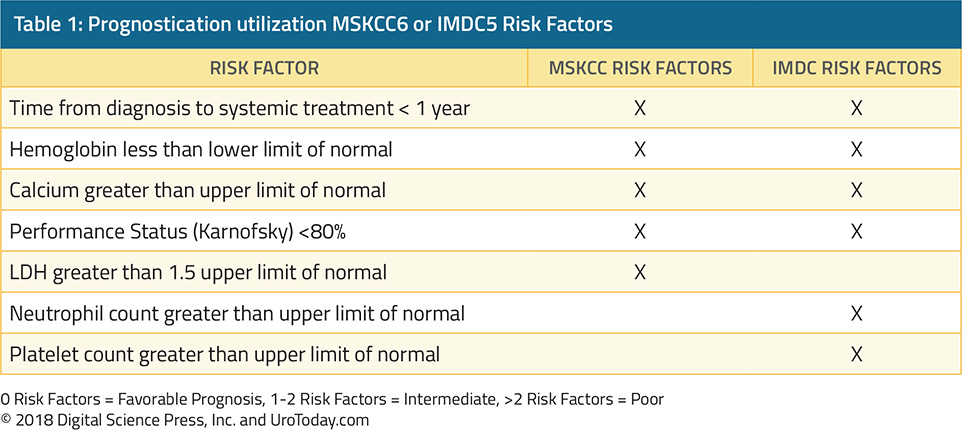

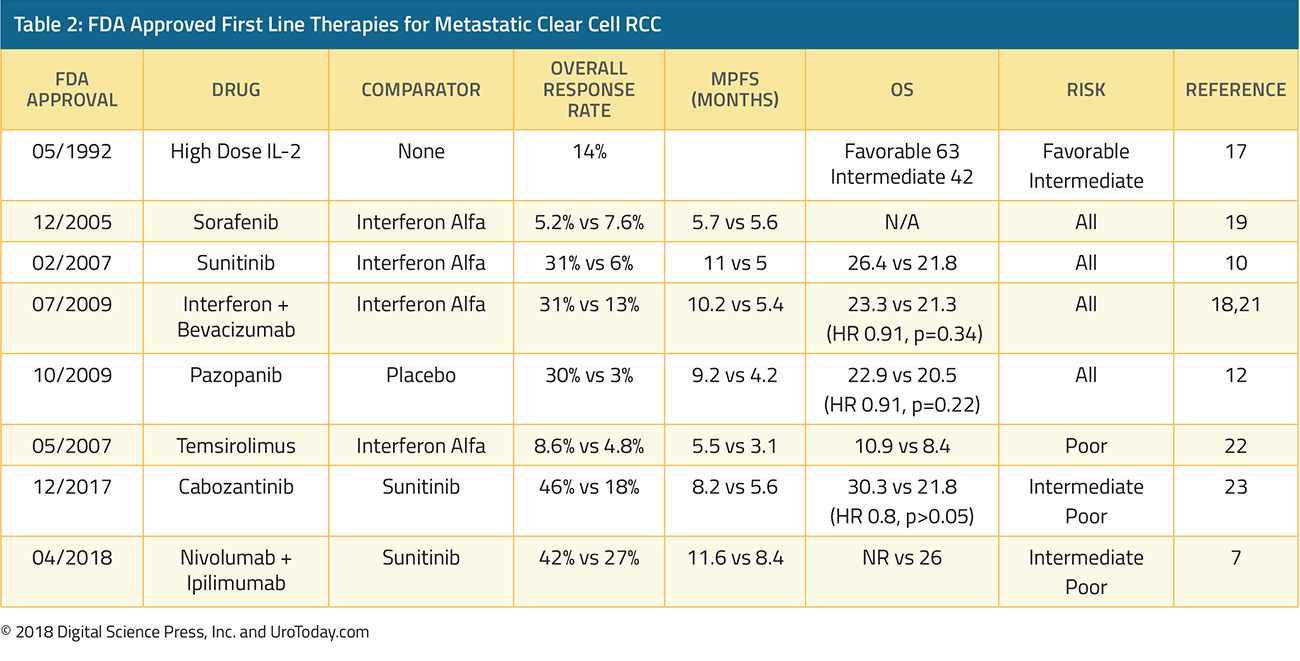

The immunologically active nature of RCC has been recognized for many years and, as a result, modulators of the immune system were among the first therapeutic targets for advanced ccRCC: interferon-alfa and interleukin-2 were among the only available treatment options prior to 2005. However, despite a response rate between 10 to 15%5, even among patients treated at a center of excellence, median overall survival was only 30 months in favorable risk patients, 14 months in intermediate risk patients and 5 months in poor risk patients6. Interleukin-2 had similar response rates to interferon-based therapies (~15 to 20%)7, but distinctly had evidence of durable complete responses in approximately 7 to 9% of patients8. This observation led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of high-dose IL-2 in 1992. However, IL-2 is associated with significant toxicity which has limited its widespread use.

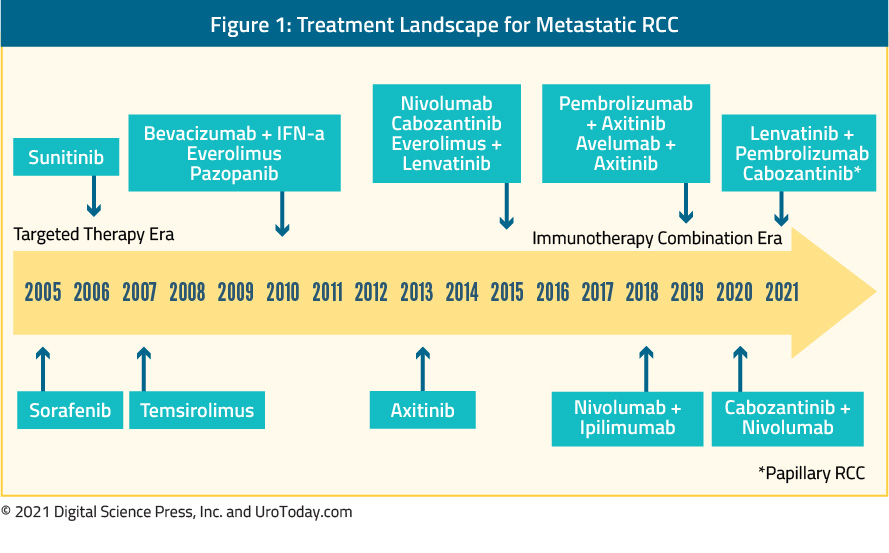

The more recent past includes the “targeted therapy” era which began with the introduction of sorafenib in 2005 followed by sunitinib in 2006 and temsirolimus in 2007, along with a number of other agents in the years that followed.

These treatments were developed based on work into the molecular biology underlying ccRCC through targeting of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). This pathway plays a key role in regulating HIF-α, thus modulating the pathway between abnormalities in VHF and proliferation.

While no longer used as monotherapy in the first-line setting, bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A, was the first inhibitor of the VEGF pathway used in clinical trials. In head-to-head trials against interferon-alfa, the addition of bevacizumab to interferon resulted in significant improvements in response rate and progression-free survival9,10.

In contrast, tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKIs) quickly became standard of care, used as first-line monotherapy. For nearly 15 years, sunitinib was the standard of care, and as such, it has formed the control comparison for testing of newer approaches. As with bevacizumab, TKIs also target the VEGF pathway, through inhibition of a combination of VEGFR-2, PDGFR-β, raf-1 c-Kit, and Flt3 (sunitinib and sorafenib). As alluded to above, sorafenib was one the first molecularly targeted agents clinically available, in 2006, based on demonstrated biologic activity in ccRCC. However, despite FDA approval, sorafenib was quickly supplanted by sunitinib as a first-line VEGF inhibitor. Sunitinib was first tested among patients who had previously received cytokine therapy and then, in a pivotal phase III trial, demonstrated superiority (both in terms of progression free survival and quality of life) in a head-to-head comparison with interferon-α11. Since the approval of sunitinib and sorafenib, there has been development and subsequent approval of many other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. For the most part, the goal of these agents has been to reduce the toxicity of VEGF inhibitors while retaining oncologic efficacy. Comparative data of pazopanib and sunitinib have demonstrated non-inferior oncologic outcomes with decreased toxicity among patients receiving pazopanib12. Axitinib was evaluated first as second-line therapy13 and then in the first-line setting compared to sorafenib14. Finally, tivozanib has been compared to sorafenib among patients who had not previously received VEGF or mTOR-targeting therapies. While this study demonstrated tivozanib’s activity, it was not FDA approved and it therefore not used.

Most recently, cabozantinib, a multikinase inhibitor (acting on tyrosine kinases including MET, VEGF receptors), and TAM family of kinases (TYRO3, MER, and AXL), has been approved for the first-line treatment of mRCC based on the phase II CABOSUN trial. In the initial report of this study, cabozantinib demonstrated significantly improved progression free survival (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.95), compared to sunitinib in the first line treatment of patients with intermediate or poor risk mRCC15. In an updated analysis utilizing independent PFS review, comparable PFS results were observed (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.74)16. However, this trial has yet to demonstrate an overall survival benefit to cabozantinib compared to sunitinib (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.21).

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors were developed in parallel to VEGF inhibitors. Unlike TKIs, for the most part, these agents have not been used in first-line therapy, though temsirolimus has been used in patients with poor-risk disease based on a comparison or temsirolimus, interferon, and the combination in 626 patients with pre-defined poor risk metastatic RCC who had not previously received systemic therapy17. Patients who received temsirolimus had significantly improved overall survival compared to those receiving interferon-alfa (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.92).

In addition to the recent, though now well-established, role of immunotherapy in patients with mRCC, there remains ongoing interest in the development of targeted therapies based on our understanding of mRCC biology. Notably, on the basis of an understanding of ccRCC carcinogenesis, the potent, selective, small molecular HIF-2α inhibitor belzutifan (MK-6482) was granted priority review by the FDA for patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) associated RCC. This approval was provided based on the phase II Study-004 trial among patients with renal tumors not requiring surgical intervention (NCT03401788). In data presented at ASCO-GU 2021, treatment with belzutifan was associated with an overall response rate of 36.1% (95% confidence interval 24.2-49.4%). MK-6482 also demonstrated benefits in non-RCC tumors including pancreatic lesions and central nervous systemic hemangioblastomas. This novel therapy was relatively well tolerated with 13% experiencing grade 3 treatment-related adverse events and none experiencing grade 4 or 5 treatment-related adverse events. While this approval was based on treatment in patients with renal masses not requiring surgical intervention, there are ongoing phase III trials of belzutifan both as monotherapy and in combination regimes as first-line treatment for advanced ccRCC.

The Return of Immunotherapy for Advanced RCC

While the cytokine era faded with the introduction of targeted therapies, the immunologic basis for mRCC treatment re-emerged around 2015 with the use of nivolumab monotherapy for patients who had previously received systemic therapy.

Published now more than 3 years ago, CheckMate 214 was the first study to demonstrate a benefit for immune checkpoint inhibitors in the first-line treatment of mRCC, showing an overall survival (OS) benefit for first-line nivolumab + ipilimumab vs sunitinib18. This trial randomized 1096 patients to the combination immunotherapy approach of nivolumab + ipilimumab (550 patients) or sunitinib (546 patients). Most patients had intermediate or poor risk disease (n=847). OS was significantly improved in the overall patient population; however, stratified analyses provide more nuanced results with benefits restricted to those with intermediate or poor-risk RCC while, in patients with favorable risk disease, progression-free survival and overall response rate were higher among patients who received sunitinib.

Since the initial publication, there have been a number of follow-up and subgroup analyses from CheckMate 214. Long-term follow-up among patients with at least four years of follow-up was reported at ESMO 2020 by Dr. Albiges. Among these patients, in the intention-to-treat population, results were very similar to the initial analysis previously published with the combined nivolumab + ipilimumab approach continuing to demonstrate superiority (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.81). In sub-groups defined according to IMDC criteria, those with intermediate or poor risk had improved survival with nivolumab/ipilimumab (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.78) while there continued to be no appreciable difference between treatment approaches among those with favorable risk disease (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.40). Presented at the same meeting, Dr. Regan and colleagues used these long-term follow-up data to assess a novel outcome metric, treatment-free survival with and without toxicity. The rationale for this approach is that conventional measures (OS, rPFS, etc) may not fully capture the effects on immuno-oncology (IO) approaches, particularly patients may have long periods of disease control without subsequent anticancer therapy following discontinuation of IO regimes. Thus, the authors defined treatment free survival (TFS), as the time between protocol therapy cessation and subsequent systemic therapy or death. They stratified this as TFS with or without toxicity by counting the number of days with ≥1 grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events reported. As of 42-months of follow-up, 56% of patients randomized to nivolumab + ipilimumab and 47% of those randomized to sunitinib were alive with 13% and 7%, respectively, remaining on their original therapy. A further 31% of patients randomized to nivolumab + ipilimumab and 12% of those randomized to sunitinib were surviving free of subsequent, second line therapy. 42-month restricted TFS was higher for patients randomized to nivolumab + ipilimumab (7.8 months) than those randomized to sunitinib (3.3 months). Toxicity-free TFS was 7.1 months and 3.0 months, respectively. In each case, the 95% confidence interval of the difference in median TFS excluded unity demonstrating that these are significant differences. Unlike the differences in PFS and OS which appear to be restricted to patients with intermediate and poor risk disease, Dr. Regan and colleagues showed that the benefits in TFS were dramatic in patients with both IMBC intermediate and poor risk disease (median TFS 6.9 vs 3.1 months) and favourable risk disease (median TFS 11.0 vs 3.7 months).

One of the final important subgroup analyses comes from Dr. Escudier and colleagues who demonstrated that the objective response rate was stable across increasing numbers of IMDC risk factors (from zero to 6) for those who received nivolumab and ipilimumab, while the ORR in patients treated with sunitinib decreased with an increasing number of IMDC risk factors19.

The BIONIKK trial, an open-label, phase II biomarker-driven randomized trial, was also presented as ESMO 2020. This trial relied upon previous analyses which demonstrated that immune and angiogenic signatures can allow for the differentiation of four groups of patients (ccrcc1-4) with immune and angiogenic high/low features, which could allow better identification of responders to either nivolumab, nivolumab + ipilimumab or TKI. ccrcc1 “immune-low” and ccrcc4 “immune-high” tumors have been associated with the poorest outcomes, whereas ccrcc2 “angio-high” and ccrcc3 “normal-like” tumors have been associated with the best outcomes. In this biomarker driven trial, patients with ccrcc1 and ccrcc4 signatures were randomized to nivolumab versus nivolumab + ipilimumab, whereas those with ccrcc2 and ccrcc3 signatures were randomized to receive nivolumab + ipilimumab versus TKI. As a phase II trial, the primary endpoint for this study was objective response rate (ORR, RECIST1.1) per treatment and group. Secondary endpoints included PFS, OS, and tolerability. 202 patients were randomized of a targeted 187. Among patients with the ccrcc1 signature, objective response rates were higher among those who received combination therapy with nivolumab + ipilimumab (39.4%; 6.1% complete response rate) than those who received nivolumab alone (20.7%; 0% complete response rate) whereas among those with a ccrcc4 signature, objective response rates were 50.3% in those receiving the combination approach (11.8% complete response rate) as compared to 50% in those receiving nivolumab alone (7.1%). Median progression free survival among patients with the ccrcc1 signature was 8.0 months in those receiving nivolumab + ipilimumab and 4.6 months among those receiving nivolumab alone. In the ccrcc4 group, median progression-free survival was 12.2 months in the combination arm and 7.8 months in the nivolumab monotherapy arm. In patients with the ccrcc2 signature, objective response rates were 48.3% in the nivolumab + ipilimumab arm (13.8% complete response rate) and 53.8% in the TKI arm (0% complete response rate) whereas among patients with the ccrcc3 signature, 25% receiving nivolumab + ipilimumab had objective responses (0% complete response rate) and 0% receiving TKI had objective response. These are the first randomized data based on molecular risk group assessment to guide first-line therapy in metastatic ccRCC. In particular, among patients with the ccrcc4 signature, use of combination therapy may not be required and thus ipilimumab may be spared.

In terms of first line therapy, immunotherapy approaches have predominately focused on combination therapy approaches. However, in the past month, data regarding the use of pembrolizumab monotherapy has emerged20. This phase II single-arm study demonstrated an objective response rate of 36.4% among 110 enrolled patients with a median progression-free survival of 7.1 months (95% CI 5.6 to 11.0 months). Clearly, compared to the data highlighted both above from CheckMate214 and in the sections that follow, these results are inferior to combination therapy.

Combination Approaches: Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

Combination therapy has been well established in the treatment of advanced RCC, including the use of interferon-alfa and bevacizumab9,10. Following the data from CheckMate 214 demonstrating the role for immune checkpoint blockade in advanced RCC, data began to emerge on the combination of targeted therapies with checkpoint inhibitors.

The first of these studies was IMmotion151, first presented at GU ASCO 2018 and subsequently published, which compared first-line atezolizumab + bevacizumab vs sunitinib among 915 patients with previously untreated metastatic RCC21. The combined approach demonstrated a significant benefit in progression-free survival (11.2 months versus 7.7 months; HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.96) among the whole cohort of patients and had lower rates of significant (grade 3-4) adverse events (40% vs 54%).

Subsequently, further combination approaches have been approved on the basis of published phase III trials, including pembrolizumab + axitinib (KEYNOTE-426) and avelumab + axitinib (JAVELIN Renal 101). Additionally, the recent presentation and publication of CheckMate-9ER and CLEAR have added the combination of nivolumab + cabozantinib and lenvatinib + pembrolizumab, respectively, to the armamentarium of first line mRCC treatment.

In KEYNOTE-426, 861 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC, predominately with intermediate or poor risk disease, who had not previously received systemic therapy were randomized to pembrolizumab + axitinib or sunitinib and followed for the co-primary endpoints of overall survival and progression free survival22. While median OS was not reached, patients who received pembrolizumab + axitinib had improved OS (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.74) and progression free survival (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.84), as well as overall response rate. These results were consistent across subgroups of demographic characteristics, IMDC risk categories, and PD-L1 expression level. Grade 3 to 5 adverse events were somewhat more common among patients getting pembrolizumab and axitinib, though rates of discontinuation were lower.

Similarly, JAVELIN Renal 101 randomized 886 patients to avelumab + axitinib or sunitinib23. Again, the preponderance of patients had IMDC intermediate or poor risk disease. In this analysis the primary endpoints were PFS and OS in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors. Notably, 560 of the 886 patients had PD-L1 positive tumors. Among the PD-L1 positive subgroup, progression free survival (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.79) was improved in patients receiving avelumab + axitinib compared to sunitinib while OS did not significantly differ (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.28). In the overall study population, progression-free survival was similarly improved, as compared to the PD-L1 positive population (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.84).

Third, in data initially presented at ESMO 2020 and published in February 2021, the CheckMate-9ER trial (NCT03141177), randomized 651 patients in a 1:1 fashion to nivolumab + cabozantinib or sunitinib, in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma, with randomization was stratified by IMDC risk score, tumor PD-L1 expression, and region. The primary outcome was progression-free survival with overall survival, objective response rate, and toxicity comprising important secondary outcomes. Over a median follow-up of 18 months, median progression-free survival was significantly longer among those randomized to nivolumab + cabozantinib (16.6 months) than those randomized to sunitinib (8.3 months), with a relative difference of 49% (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.64) as was OS (medians not reached; HR 0.60, 98.89% CI 0.40 to 0.89). Notably, these benefits were seen consistently across pre-specified subgroups defined according to IMDC risk categories and PD-L1 expression. Any grade treatment related adverse events were common in both groups: 96.6% among those receiving nivolumab + cabozantinib and 93.1% among those receiving sunitinib. High grade events (grade 3 or greater) were somewhat higher among those receiving nivolumab + cabozantinib (60.6% vs 50.9%). One grade 5 event occurred in the nivolumab + cabozantinib arm while 2 occurred in the sunitinib treated group. Notably, quality of life was maintained for those receiving nivolumab + cabozantinib while there was a decline in quality of life among those receiving sunitinib.

The fourth kinase inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor combination is lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, based on the CLEAR study presented at ASCO-GU 2021 and simultaneously published24. As with the other three trials, CLEAR enrolled patients with previously untreated advanced RCC. Unlike the other trials, this was a three-arm randomization in a 1:1:1 fashion to lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily + pembrolizumab 200 mg IV every 3 weeks; or lenvatinib 18 mg + everolimus 5 mg orally once daily; or sunitinib 50 mg orally once daily (4 weeks on/2 weeks off in 6-weekly cycles). The authors assessed the primary endpoint of progression-free survival by Independent Review Committee per RECIST v1.1 with key secondary endpoints including OS, objective response rate (ORR) and safety. The authors randomized 1069 patients, 355 who received lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, 357 who received lenvatinib and everolimus, and 357 who received sunitinib. The baseline characteristics of the study population were in keeping with those observed in other first-line mRCC trials. Notably, intermediate and poor risk disease comprised just over 70% of the cohort. Over a median follow-up of 27 months, PFS was significantly improved among patients receiving lenvatinib and pembrolizumab (median 24 months) vs sunitinib (median 9 months; HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.32–0.49) and among patients receiving lenvatinib and everolimus (median 15 months) vs sunitinib (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.80). The benefit of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab versus sunitinib with respect to progression-free survival was consistent across many subgroups, comprising age, sex, geographic region, PD-L1 expression, IMDC risk group, prior nephrectomy, and sarcomatoid features. Further, OS was significantly longer among patients who received lenvatinib and pembrolizumab compared to sunitinib (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49–0.88), whereas there was no significant difference in OS for patients receiving lenvatinib and everolimus compared to sunitinib (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.88–1.50). As with progression-free survival, these findings were consistent across all relevant tested subgroups for the comparison of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, except patients with favorable risk group. Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 72% of pts in the lenvatinib and pembrolizumab arm and 73% of pts in the lenvatinib and everolimus arm compared with 59% of pts in the sunitinib arm.

While not yet ready for clinical practice, interesting data from COSMIC-021, a multicenter phase 1b study, evaluating the combination of cabozantinib + atezolizumab in various solid tumors (NCT03170960), including first-line treatment of clear cell RCC, was presented at ESMO 2020. Cabozantinib, a standard-of-care for the treatment of advanced RCC, is potentially particularly well suited to combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors as it promotes an immune-permissive environment which may enhance response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. In combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, cabozantinib has shown promising activity for other tumor types including urothelial carcinoma, castration-resistant prostate cancer, lung cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The ccRCC subset of the COSMIC-021 trial included 10 patients in the dose escalation stage and 60 in the expansion stage of the study. Patients were enrolled sequentially to receive atezolizumab 1200 mg IV every three weeks with either cabozantinib 40 mg (dose level 40 [DL40], n=34) or cabozantinib 60 mg (DL60, n=36) PO daily in each stage as first line therapy. The primary endpoint for this trial is the ORR per RECIST v1.1 by investigator, the secondary endpoint was safety, and exploratory endpoints include PFS and correlation of biomarkers with outcomes. For DL40, the ORR was 53% (80% CI 41-65), with one complete response (3%) and 17 partial responses (50%), the disease control rate was 94%, duration of response was not reached (range: 12.4 months to not reached), and the median time to objective response was 1.4 months (range: 1-19). For DL60, the ORR was 58% (80% CI 46-70), with four complete responses (11%) and 17 partial responses (47%), the disease control rate was 92%, the median duration of response was 15.4 months (range: 8.1 to not reached), and median time to objective response was 1.5 months (range: 1-7). For DL40, the median PFS was 19.5 months (95% CI 11.0 to not reached) compared to 15.1 months (95% CI 8.2-22.3) for DL60. This approach is currently being further investigated in the CONTACT-03 trial (NCT04338269), a phase III RCT comparing atezolizumab + cabozantinib to cabozantinib alone in patients who had previously received immune checkpoint therapy.

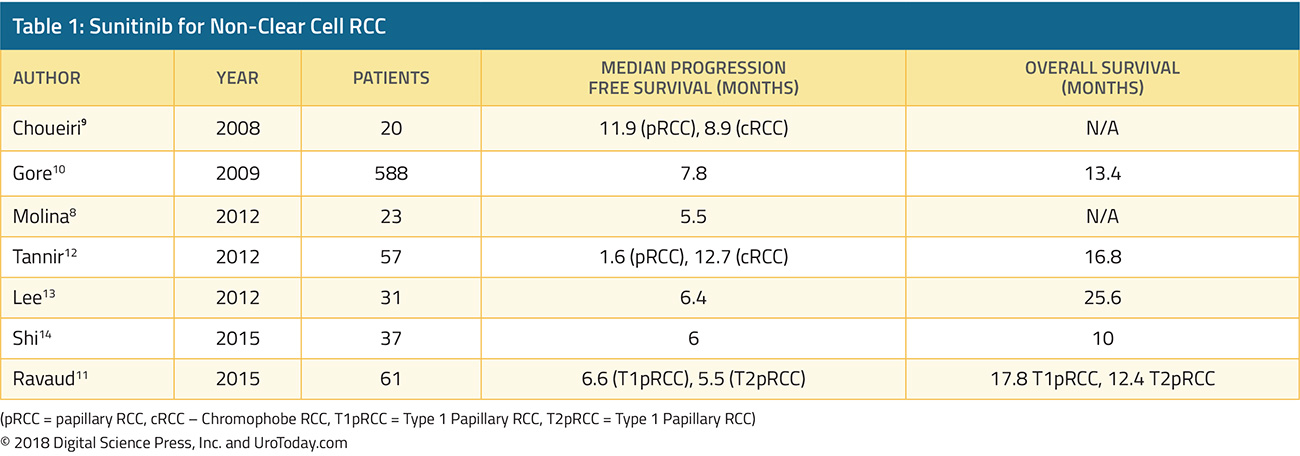

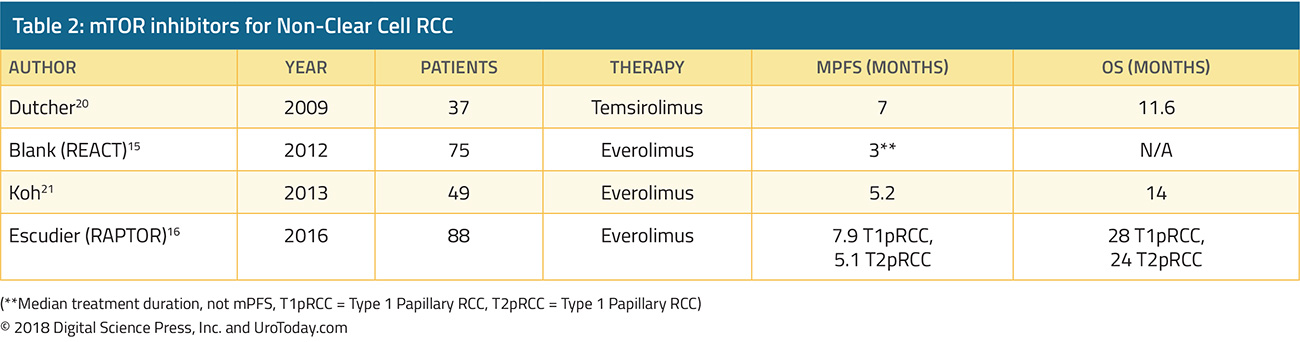

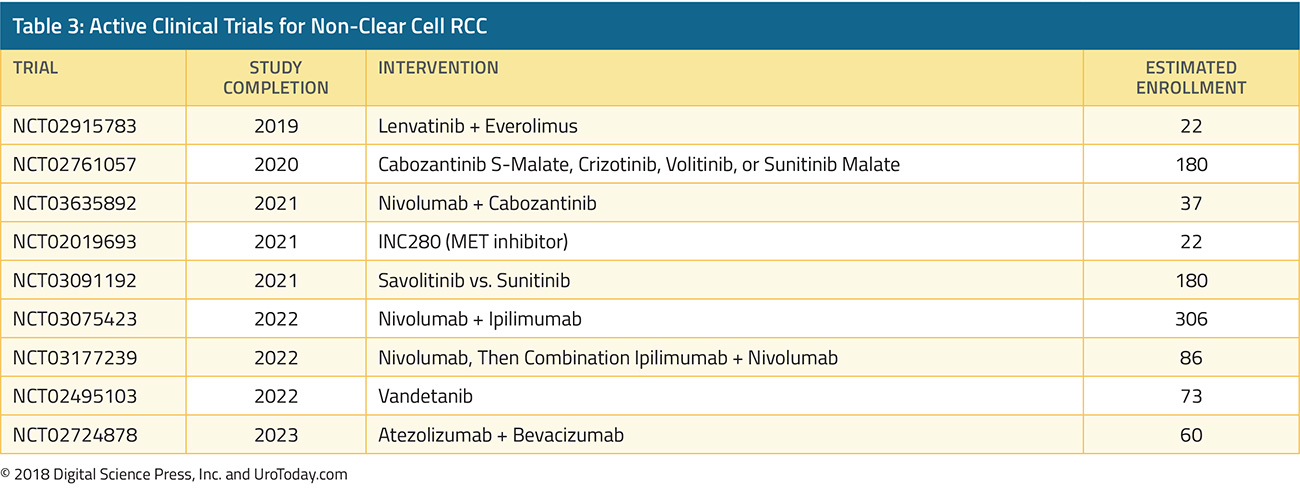

Non-Clear Cell Histology

In general, randomized trials in advanced RCC have focused on patients with clear cell histology. As a result, there have been little direct data to guide care and we have had to rely on extrapolation from data derived among patients with clear cell histology. However, retrospective data have supported the activity of cabozantinib monotherapy in patients with advanced non-clear cell disease25. At ESMO 2020, Dr. McGregor and colleagues reported a prospective evaluation of the use of cabozantinib + atezolizumab in a subcohort of patients with non-clear cell histology the COSMIC-031 trial. Notably, in this cohort, patients were allowed up to one previously line of TKI (but not previous checkpoint inhibitor therapy or cabozantinib). At the time of data cut-off, 30 patients had been enrolled and followed for a median of 13.0 months. The cohort included 15 patients with papillary, 7 patients with chromophobe, and 8 patients with other histology. Five patients had received previous systemic therapy while 25 (83%) were treatment naïve. Confirmed objective response rate per RECIST v1.1 was 33% (80% confidence interval 22 to 47%), and there were 10 patients with partial responses (papillary, n=6; chromophobe, n=1; ccRCC, n=1; translocation, n=1; and unclassified, n=1) but there were no complete responses, although partial responses occurred in all IMDC risk groups. The median progression-free survival was 9.5 months (95% CI 5.5 to not reached). Notably, patients with nccRCC will be included in the previously mentioned CONTACT-03 trial.

In addition to this combination approaches, a phase II single arm study of pembrolizumab monotherapy in non-clear cell mRCC was recently published26. This phase II single-arm study enrolled 165 patients, of whom 72% had papillary disease, 13% had chromophobe, and 16% had unclassified RCC histology with 70% having intermediate or poor-risk disease, per IMDC criteria. Over a median follow-up of 32 months from enrollment, the objective response rate was 26.7%, with variation according to histology: 29% in those with papillary disease, 10% In those with chromophobe, and 31% for those with unclassified histology. Overall, the median progression-free survival was 4.2 months.

The SAVIOUR phase III randomized controlled trial assessed savolitinib as compared to sunitinib in patients with MET-driven papillary RCC27. After 60 randomized patients, external data on the PFS with sunitinib in patients with MET-driven disease became available and led to closure of the study. At the time of closure, progression-free survival, overall survival, and objective response rates were all numerically higher in patients receiving savolitinib, though the differences were not statistically significant (eg. for PFS, HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.36).

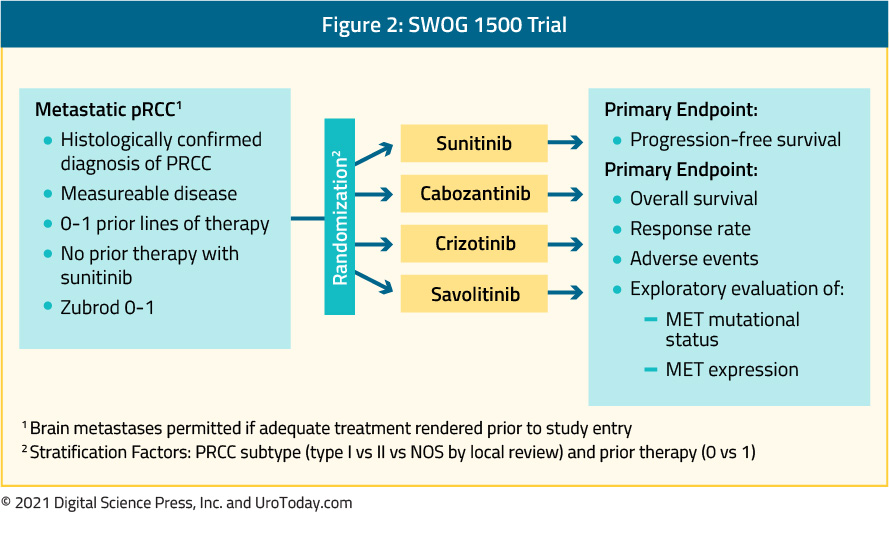

Additionally, at ASCO-GU 2021, the four-armed SWOG 1500 trial was presented and simultaneously published in the Lancet28. This study recruited patients with pathologically verified papillary RCC with measurable metastatic disease and Zubrod performance status 0-1. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had received up to 1 prior systemic therapy excluding VEGF-directed agents. Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 fashion to receive either sunitinib, cabozantinib, crizotinib, or savolitinib:

There were 152 patients that were enrolled of whom 5 were ineligible. The included patients had a median age of 66 (range:29-89) and the majority (76%) were male. The vast majority (92%) had not received prior systemic therapy. Median PFS was significantly higher with cabozantinib relative to sunitinib (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.37-0.97). Objective response rates were also higher with cabozantinib than with sunitinib, crizotinib, and savolitinib, with two complete responses and eight partial responses noted among the 44 patients randomized to cabozantinib. Median OS was 20 months for those receiving cabozantinib and 16.4 months for those receiving sunitinib.

Treatment Selection

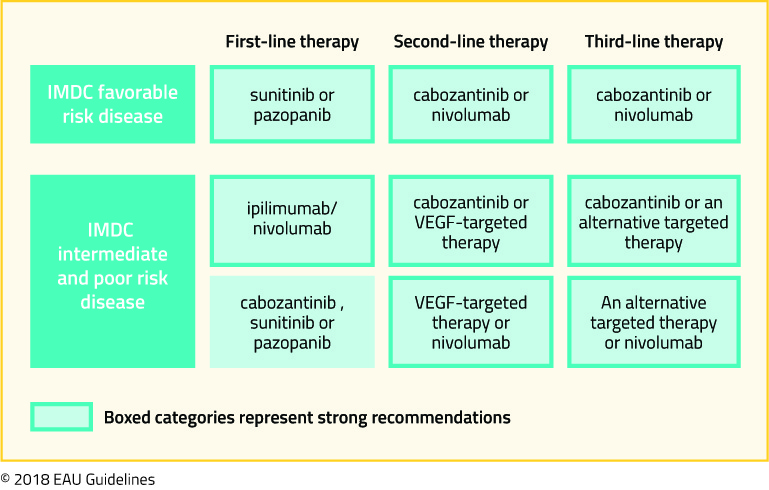

As highlighted above, there are a number of treatment approaches which have, in phase III RCTs, demonstrated superiority to sunitinib in first-line treatment of clear cell mRCC including atezolizumab + bevacizumab, nivolumab + ipilimumab, pembrolizumab + axitinib, avelumab + axitinib, nivolumab + cabozantinib, pembrolizumab + lenvatinib. As highlighted in the BIONNIKK trial, a tumor-derived signature may allow for rationale treatment selection, however, prior to this, IMDC risk categories and PD-L1 testing may provide some guidance. Additionally, authors have considered cost-effectiveness analyses to help guide treatment selection29,30. However, as may be expected, varying the assumptions of these models may change the preferred treatment options. Numerous ongoing trials will continue to shape this rapidly evolving disease space and individual treatment choice will depend on the patient, physician, and system factors with guidelines likely to continue to recommend multiple options.

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc, Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor Surgery/Urology at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Georgia Cancer Center

Published Date: March 2021