Charles J Ryan, MD, is a leader in medical oncology and was the primary investigator for the COU-AA-302 clinical trial, which led to FDA approval of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone as the first oral therapy for treatment in chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Dr. Ryan is Professor of Clinical Medicine and Urology and Thomas Perkins Distinguished Professor in Cancer Research, and Program Leader, Genitourinary Medical Oncology at the University of California-San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Francisco, CA. In the following article, he reflects on the highlights of the COU-AA-302 journey, including the pioneering results and methodology of the study, as well as the voice of the study results including the secondary endpoints on patient outcomes such as pain, time to opiate use, and functional status.

Before the COU-AA-302 trial, there was no validated level I evidence showing that treatments other than chemotherapy had value in the chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) population. Many of these patients, particularly those with no or minor symptoms, did not want, and did not need, chemotherapy. So there was a great need to develop treatments that could be given in place of, or prior to, chemotherapy.

In its final overall survival analysis, the COU-AA-302 trial confirmed the benefit of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, given prior to docetaxel, in men with mCRPC. Although the final overall survival benefit was less robust than initially anticipated, the trial did prove conclusively that abiraterone acetate plus prednisone was a standard of care prior to starting a docetaxel in this disease.

As we prepared for the trial, we discovered an important fact: Only approximately 45% of men who had mCRPC received chemotherapy. More than half of patients in this setting were not being offered any treatment beyond standard androgen deprivation therapy. Once this therapy failed, many patients were not offered any other options. As a result, there was a real need for new treatments in men diagnosed with mCRPC who have no or few symptoms.

In the COU-AA-302 trial, 1088 patients were randomly assigned to receive either abiraterone acetate (1000 mg once daily) plus prednisone (5 mg twice daily) or prednisone plus placebo. The primary trial endpoints were radiographic progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). The results of the planned interim analysis performed after 43% of expected deaths had occurred showed that the median radiographic PFS rate was 16.5 months with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and 8.3 months with prednisone plus placebo (hazard ratio for abiraterone-prednisone vs. prednisone-placebo .53; P <0.001).1

The interim analysis also indicated that over a median follow-up period of 22.2 months, OS rates were improved with the abiraterone-prednisone regimen (median for abiraterone-prednisone not reached in the initial analysis vs. 27.2 months for prednisone plus placebo. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone also showed superiority over prednisone plus placebo in time to initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy, opiate use for cancer-related pain, prostate-specific antigen progression, and decline in performance status.1

Due to the positive initial results for radiographic PFS rates in the COU-AA-302 study, the data and safety monitoring board decided to unblind the trial, which led to significant crossover in the study; patients who had been on placebo were allowed to receive abiraterone acetate.

It was the right thing to do ethically and from a patient-care perspective, but it also created a challenge for us as researchers. As a result of patient crossover in the trial, the overall survival data took longer than expected to mature and reach statistical significance.

Many people don’t realize that while there was a trend toward improved survival rates with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in the interim analysis, the P value for the difference in OS rates was below the standard .05. This may have been due partly to the low number of events and/or the fact that prednisone was an active control. In the trial, approximately 29% of patients treated with prednisone experienced a 50% or greater decline in their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values in the interim analysis.

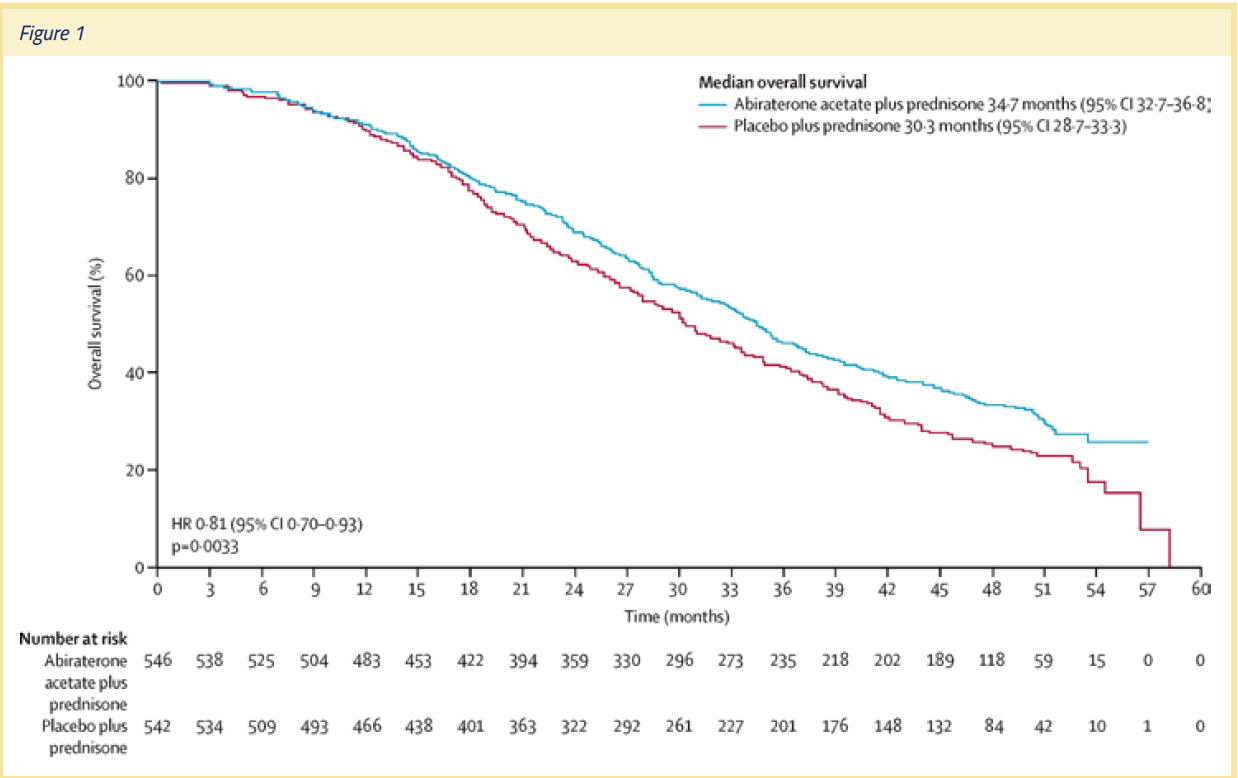

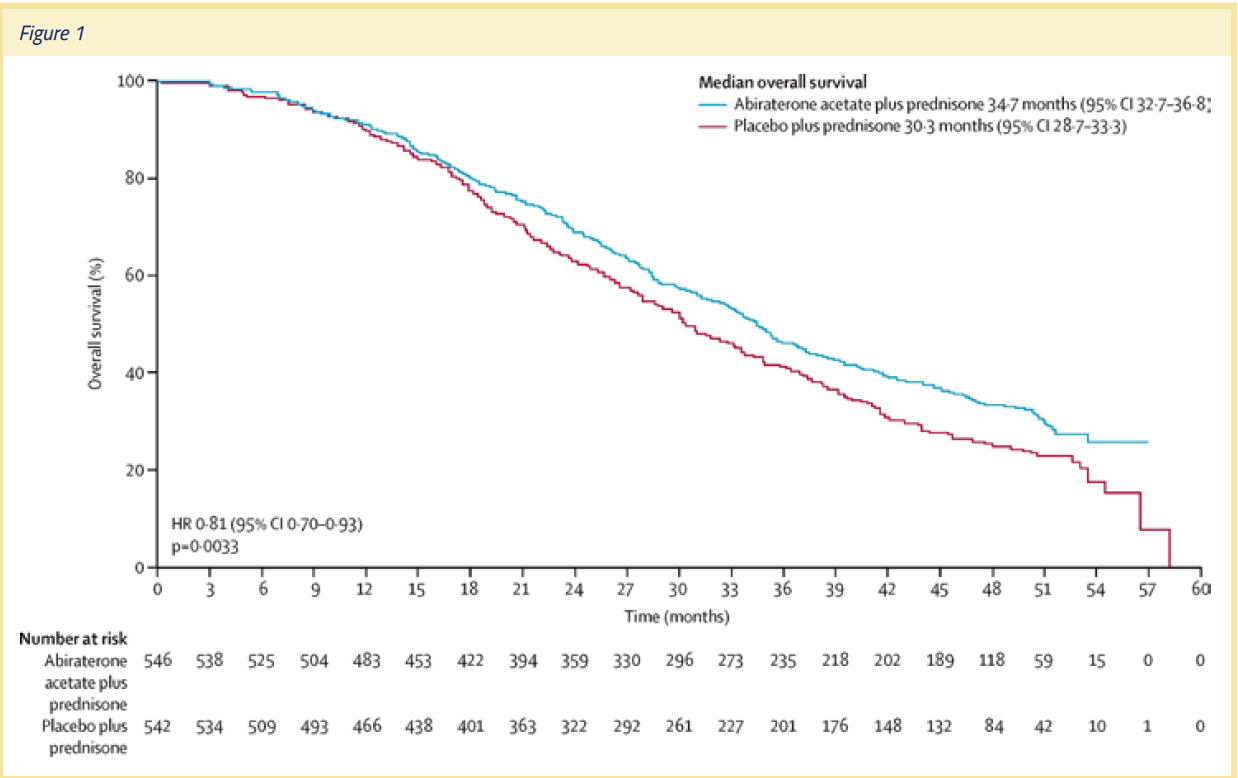

Yet, the final analysis, published in Lancet Oncology in 2015, showed that OS rates with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone were significantly longer (34.7 months) than with prednisone plus placebo (30.3 months) (P =.0033).2 The difference in the OS rates in the final analysis was noteworthy, not only because it was achieved despite considerable patient crossover to abiraterone acetate from placebo, but also because some patients in the placebo group received subsequent docetaxel.3 (See Figure 1)

The final analysis also showed that the effect of abiraterone acetate on OS rates was not dependent on whether or not a patient received prior chemotherapy. The OS rates achieved with abiraterone acetate was also not dependent on the Gleason score at initial diagnosis, or duration of previous androgen deprivation therapy. Thus, the COU-AA-302 trial provided a strong rationale for the use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy early in the clinical course of mCRPC. As oncologists, we should not wait for symptoms to occur—we should prevent symptoms by being proactive with our treatment regimens. The evolution of the survival curve in this trial, and the fact that it was positive, helped to drive home that point.

The final safety results for the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group in the COU-AA-302 trial were also positive. In fact, the safety outcomes in the study were similar to those reported in studies on men with mCRPC who received docetaxel chemotherapy. Grade 3 and 4 adverse events affected 54% of patients in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group and 44% of men in the prednisone plus placebo group. The most common adverse events in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group were fluid retention/edema, hypokalemia, hypertension, and cardiac disorders. Adverse events that led to discontinuation occurred in 13% of men in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group and 10% of men in the prednisone plus placebo group.

In addition to its positive final outcomes, the COU-AA-302 clinical trial was also remarkable because it established radiographic PFS as a response biomarker that was highly correlated with overall survival. In the study, radiographic PFS was defined as the time from random assignment to the first occurrence of progression on either bone scan, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging as defined by modified RECIST criteria; or death resulting from any cause. Bone and CT scans were obtained every 8 weeks during the first 24 weeks of the trial and every 12 weeks thereafter.4

COU-AA-302 was the first trial in which radiographic PFS was a co-primary endpoint, and it allowed us for the first time to show that this is a meaningful endpoint.

The first interim analysis of the trial results indicated that treatment with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone led to a 57% reduction in the risk of radiographic disease progression or death compared to treatment with prednisone plus placebo. The second interim analysis of OS rates showed that use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone led to an estimated 25% decrease in the risk of death, and radiographic PFS rates were positively associated with OS rates in both treatment groups. These results suggest that the objective, prospectively defined endpoint of radiographic PFS survival could serve as a response indicator biomarker that can be evaluated in future studies.

As a result of the COU-AA-302 trial, other research groups can now devise and run clinical trials that use radiographic PFS as a primary endpoint. Since radiographic PFS has been validated as an endpoint correlated with OS, researchers don’t have to wait for final OS data to mature to be able to determine whether a trial is a success or failure. As a result, studies can be performed and completed more rapidly, and new therapies made available to patients much earlier.

In addition to showing that abiraterone acetate plus prednisone delayed radiographic PFS and improved OS rates, the COU-AA-302 clinical trial was a remarkable effort because of the amount of data we collected on quality of life and performance preservation. The study showed that abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy has three functions—to preserve function, prevent progression and complications, and prolong life.

The patients enrolled in the COU-AA-302 trial had a moderately good quality of life and functional level at baseline. In addition to prolonging radiographic progression-free survival and overall survival, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy allowed patients to preserve function, and prevented complications of their disease. That’s a key message, because for the first time in the treatment of mCRPC, we were treating patients who were in pretty good shape, and telling them: “This therapy won’t make you feel sick, and, better yet, it will help you preserve your quality of life.”

Prior therapies were aimed at alleviating the symptoms of patients who were already suffering due to the effects of prostate cancer. The COU-AA-302 trial was a departure from that approach, since it aimed to prevent complications and painful symptoms. Most patients want to be able to begin therapy before they have painful symptoms—therapy that allows them to preserve their pain-free status.

The endpoints of the trial included patient-reported outcomes such as pain and functional status. Pain was measured using the Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form) (BPI-SF) questionnaire, and included notable measures of pain such as intensity (the average pain and worst pain felt during a day) and the extent to which pain interfered with daily activities. The pain measures were recorded on questionnaires during clinic visits at baseline, day 1 of each treatment cycle, and at the end of the treatment cycle.

Functional status was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) scale. This scale included the FACT-General (made up of 4 subscales that evaluate different domains of general functional status) and the Prostate Cancer Subscale (PCS), which evaluates prostate cancer-specific symptoms. To report their functional status, the patients filled out questionnaires during clinic visits at baseline; day 1 of cycles 3, 5, 7,10 and every 3rd cycle thereafter; and at the end of treatment.

The results of the COU-AA-302 trial revealed that the median time to functional status degradation was significantly longer in patients on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone vs. patients on prednisone plus placebo as measured by both the FACT-G and PCS. Patients in the treatment group were also significantly more likely to preserve their function in terms of physical well-being, functional well-being, emotional well-being, and social/family well- being.

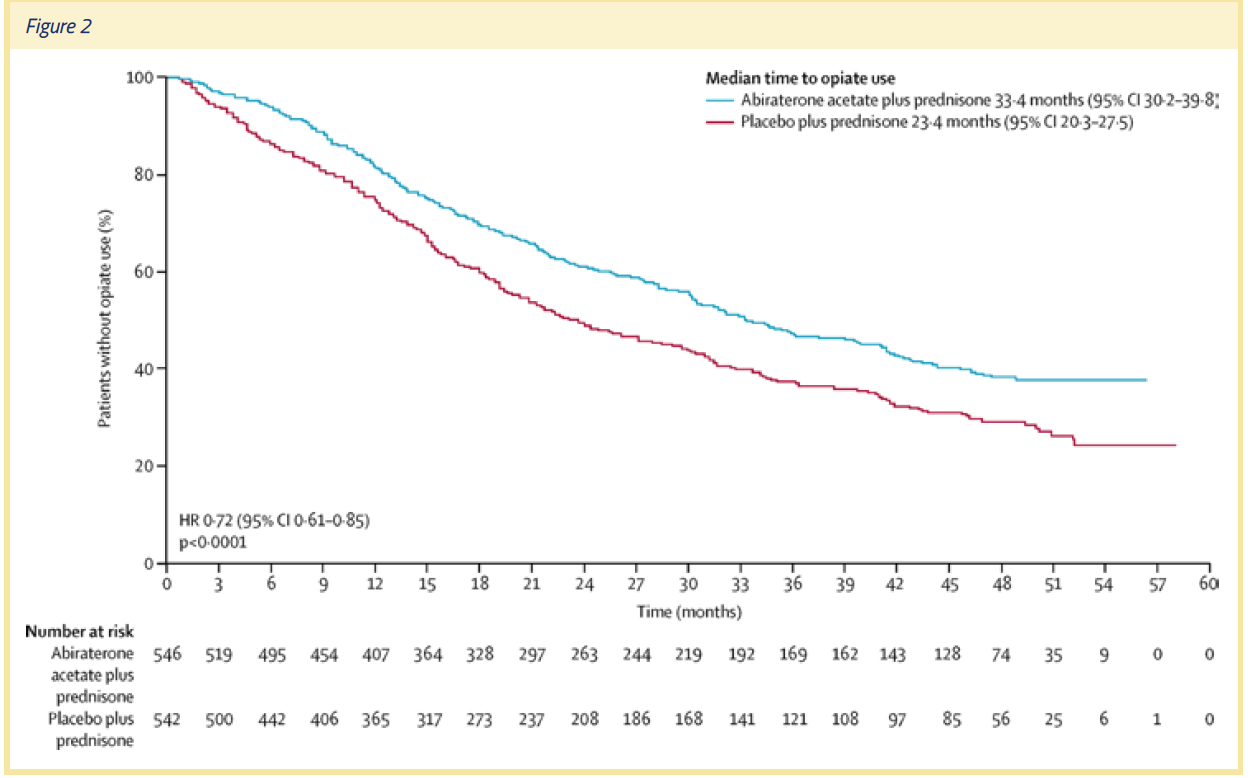

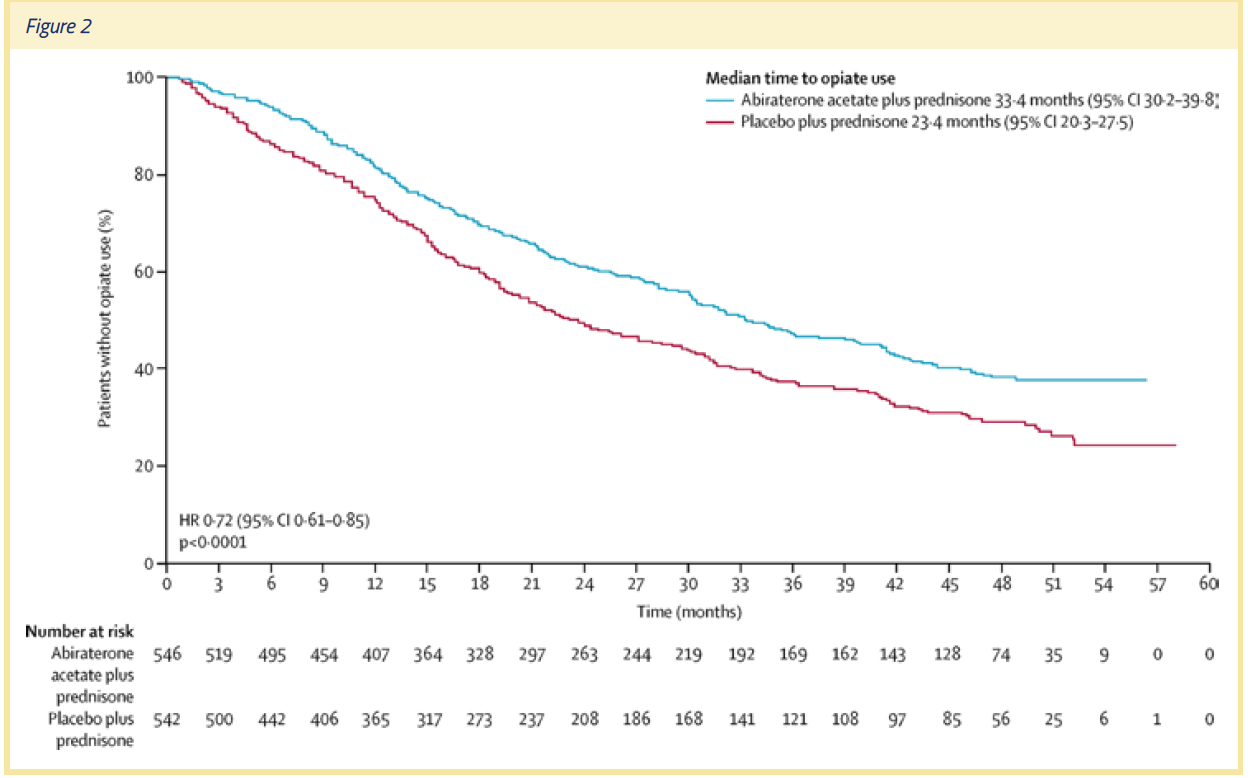

The COU-AA-302 trial outcomes also showed that patients in the active treatment group were less troubled by pain. The median time to progression of average pain intensity was 26.7 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 18.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.0490). The median time to progression in pain interference was 10.3 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 7.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.005). In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, time to progression (at the 25th percentile) of worst pain intensity was 14.8 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 12 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.045). (See Figure 2)

The COU-AA-302 trial showed definitively that the addition of abiraterone acetate to prednisone delayed the development and progression of pain and opiate use. One important piece of data that also came out of the trial was a 10-month difference in the median time to opiate use. In the final analysis, the median time to opiate use for prostate cancer-related pain was 33.4 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 23.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (HR =.72, P <.0001).

Imagine having 10 months of pain that requires opiates—and then imagine that you don’t have that pain, and don’t have to use opiates to reduce that pain. For patients, that’s a lot of time to experience a pain-free life and freedom from opiate use. So not only did abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy help preserve quality of life, it also prevented progression of the patients' disease to the point at which pain becomes a major problem. As oncologists, we want to alleviate pain and suffering, but being able to prevent pain and suffering is even better.

Pain is an important and debilitating complication of mCRPC, affecting 50% of men with metastatic disease. So understanding the impact of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy on pain is important and valuable information for decision-makers in the treatment of mCRPC, including patients, clinicians, regulators, and payers.

As well as demonstrating significant differences in OS and radiographic PFS with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, COU-AA-302 was a landmark study, because it showed that it was feasible to measure the development and progression of pain and analgesic use in a large multicenter trial. To ensure that the patient perspective is captured in clinical research on new oncology drugs, it’s vitally important to assess patient-reported outcomes on pain and function using methodologically rigorous approaches.

Written by: Charles Ryan, MD

References:

1. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. NEJM. 2012;368(2):138-148.

2. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naïve men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): Final overall survival analysis of a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:152-160.

3. De Bono JS, Smith MR, Saad F, et al. Subsequent chemotherapy and treatment patterns after abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Post hoc analysis of COU-AA-302. Eur Urol. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.033.

4. Morris MJ, Molina A, Small EJ, et al. Radiographic progression-free survival as a response biomarker in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: COU-AA-302 results. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:1356-1363.

Many people don’t realize that while there was a trend toward improved survival rates with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in the interim analysis, the P value for the difference in OS rates was below the standard .05. This may have been due partly to the low number of events and/or the fact that prednisone was an active control. In the trial, approximately 29% of patients treated with prednisone experienced a 50% or greater decline in their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values in the interim analysis.

Yet, the final analysis, published in Lancet Oncology in 2015, showed that OS rates with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone were significantly longer (34.7 months) than with prednisone plus placebo (30.3 months) (P =.0033).2 The difference in the OS rates in the final analysis was noteworthy, not only because it was achieved despite considerable patient crossover to abiraterone acetate from placebo, but also because some patients in the placebo group received subsequent docetaxel.3 (See Figure 1)

The final analysis also showed that the effect of abiraterone acetate on OS rates was not dependent on whether or not a patient received prior chemotherapy. The OS rates achieved with abiraterone acetate was also not dependent on the Gleason score at initial diagnosis, or duration of previous androgen deprivation therapy. Thus, the COU-AA-302 trial provided a strong rationale for the use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy early in the clinical course of mCRPC. As oncologists, we should not wait for symptoms to occur—we should prevent symptoms by being proactive with our treatment regimens. The evolution of the survival curve in this trial, and the fact that it was positive, helped to drive home that point.

The final safety results for the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group in the COU-AA-302 trial were also positive. In fact, the safety outcomes in the study were similar to those reported in studies on men with mCRPC who received docetaxel chemotherapy. Grade 3 and 4 adverse events affected 54% of patients in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group and 44% of men in the prednisone plus placebo group. The most common adverse events in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group were fluid retention/edema, hypokalemia, hypertension, and cardiac disorders. Adverse events that led to discontinuation occurred in 13% of men in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group and 10% of men in the prednisone plus placebo group.

In addition to its positive final outcomes, the COU-AA-302 clinical trial was also remarkable because it established radiographic PFS as a response biomarker that was highly correlated with overall survival. In the study, radiographic PFS was defined as the time from random assignment to the first occurrence of progression on either bone scan, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging as defined by modified RECIST criteria; or death resulting from any cause. Bone and CT scans were obtained every 8 weeks during the first 24 weeks of the trial and every 12 weeks thereafter.4

COU-AA-302 was the first trial in which radiographic PFS was a co-primary endpoint, and it allowed us for the first time to show that this is a meaningful endpoint.

The first interim analysis of the trial results indicated that treatment with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone led to a 57% reduction in the risk of radiographic disease progression or death compared to treatment with prednisone plus placebo. The second interim analysis of OS rates showed that use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone led to an estimated 25% decrease in the risk of death, and radiographic PFS rates were positively associated with OS rates in both treatment groups. These results suggest that the objective, prospectively defined endpoint of radiographic PFS survival could serve as a response indicator biomarker that can be evaluated in future studies.

As a result of the COU-AA-302 trial, other research groups can now devise and run clinical trials that use radiographic PFS as a primary endpoint. Since radiographic PFS has been validated as an endpoint correlated with OS, researchers don’t have to wait for final OS data to mature to be able to determine whether a trial is a success or failure. As a result, studies can be performed and completed more rapidly, and new therapies made available to patients much earlier.

In addition to showing that abiraterone acetate plus prednisone delayed radiographic PFS and improved OS rates, the COU-AA-302 clinical trial was a remarkable effort because of the amount of data we collected on quality of life and performance preservation. The study showed that abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy has three functions—to preserve function, prevent progression and complications, and prolong life.

The patients enrolled in the COU-AA-302 trial had a moderately good quality of life and functional level at baseline. In addition to prolonging radiographic progression-free survival and overall survival, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy allowed patients to preserve function, and prevented complications of their disease. That’s a key message, because for the first time in the treatment of mCRPC, we were treating patients who were in pretty good shape, and telling them: “This therapy won’t make you feel sick, and, better yet, it will help you preserve your quality of life.”

Prior therapies were aimed at alleviating the symptoms of patients who were already suffering due to the effects of prostate cancer. The COU-AA-302 trial was a departure from that approach, since it aimed to prevent complications and painful symptoms. Most patients want to be able to begin therapy before they have painful symptoms—therapy that allows them to preserve their pain-free status.

The endpoints of the trial included patient-reported outcomes such as pain and functional status. Pain was measured using the Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form) (BPI-SF) questionnaire, and included notable measures of pain such as intensity (the average pain and worst pain felt during a day) and the extent to which pain interfered with daily activities. The pain measures were recorded on questionnaires during clinic visits at baseline, day 1 of each treatment cycle, and at the end of the treatment cycle.

Functional status was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) scale. This scale included the FACT-General (made up of 4 subscales that evaluate different domains of general functional status) and the Prostate Cancer Subscale (PCS), which evaluates prostate cancer-specific symptoms. To report their functional status, the patients filled out questionnaires during clinic visits at baseline; day 1 of cycles 3, 5, 7,10 and every 3rd cycle thereafter; and at the end of treatment.

The results of the COU-AA-302 trial revealed that the median time to functional status degradation was significantly longer in patients on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone vs. patients on prednisone plus placebo as measured by both the FACT-G and PCS. Patients in the treatment group were also significantly more likely to preserve their function in terms of physical well-being, functional well-being, emotional well-being, and social/family well- being.

The COU-AA-302 trial outcomes also showed that patients in the active treatment group were less troubled by pain. The median time to progression of average pain intensity was 26.7 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 18.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.0490). The median time to progression in pain interference was 10.3 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 7.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.005). In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, time to progression (at the 25th percentile) of worst pain intensity was 14.8 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 12 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (P =.045). (See Figure 2)

The COU-AA-302 trial showed definitively that the addition of abiraterone acetate to prednisone delayed the development and progression of pain and opiate use. One important piece of data that also came out of the trial was a 10-month difference in the median time to opiate use. In the final analysis, the median time to opiate use for prostate cancer-related pain was 33.4 months in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone group vs. 23.4 months in the prednisone plus placebo group (HR =.72, P <.0001).

Imagine having 10 months of pain that requires opiates—and then imagine that you don’t have that pain, and don’t have to use opiates to reduce that pain. For patients, that’s a lot of time to experience a pain-free life and freedom from opiate use. So not only did abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy help preserve quality of life, it also prevented progression of the patients' disease to the point at which pain becomes a major problem. As oncologists, we want to alleviate pain and suffering, but being able to prevent pain and suffering is even better.

Pain is an important and debilitating complication of mCRPC, affecting 50% of men with metastatic disease. So understanding the impact of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy on pain is important and valuable information for decision-makers in the treatment of mCRPC, including patients, clinicians, regulators, and payers.

As well as demonstrating significant differences in OS and radiographic PFS with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, COU-AA-302 was a landmark study, because it showed that it was feasible to measure the development and progression of pain and analgesic use in a large multicenter trial. To ensure that the patient perspective is captured in clinical research on new oncology drugs, it’s vitally important to assess patient-reported outcomes on pain and function using methodologically rigorous approaches.

Written by: Charles Ryan, MD

References:

1. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. NEJM. 2012;368(2):138-148.

2. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naïve men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): Final overall survival analysis of a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:152-160.

3. De Bono JS, Smith MR, Saad F, et al. Subsequent chemotherapy and treatment patterns after abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Post hoc analysis of COU-AA-302. Eur Urol. 2016. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.033.

4. Morris MJ, Molina A, Small EJ, et al. Radiographic progression-free survival as a response biomarker in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: COU-AA-302 results. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:1356-1363.