(UroToday.com) The 2024 Southeastern Section of the AUA (SESAUA) annual meeting featured a State of Art Lecture by Dr. Charles Peyton discussing the management of complications following RPLND. Dr. Peyton started his presentation with a case of a 47 year old male with left neck swelling and medical history of stage IIIA NSGCT treated with left orchiectomy and BEP x 3 cycles in 1996. He was married, had several children, and worked as the lead PACU nurse.

On physical examination, he had palpable swelling of the left supraclavicular lymph nodes. A CT of the neck and chest demonstrated left cervical adenopathy and superior mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Left cervical lymph node FNA sampling suggested metastatic germ cell tumor, most likely embryonal on immunohistochemistry. Serum tumor markers showed an AFP of 2.26, beta HCG of 35.8, and LDH of 328, and his MRI of the brain was negative. PET CT images are as follows:

On further discussion, the patient stated “I think I had some abdominal lymph nodes that shrank after chemotherapy and were monitored.” Based on the aforementioned work up, his updated stage was IIIA (pT2, cN3, cM1a, S1). Dr. Peyton notes that the definition of late relapse is >2 years after chemotherapy or primary therapy, with the NCCN guidelines suggesting surgical salvage is preferred, if resectable. Although surgery is often preferred in a delayed recurrence, this patient has active embryonal M1a disease, so the decision is whether he should receive TIP chemotherapy or move straight to bone marrow transplantation and high dose chemotherapy. Dr. Peyton notes that he had a good platinum response 25 years ago, thus there is no reason to believe that TIP chemotherapy would not work, so he proceeded with 4 cycles of TIP. Following salvage chemotherapy, his AFP was 2.3, beta HCG 1.7, and LDH 198. A CT chest/abdomen/pelvis was overall improved, with a decrease in the supraclavicular and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, an unchanged 10 mm right middle lobe lung nodule, an interaortocaval 3 x 17 cm lymph node, and a calcified 2.4 x 2.5 cm aortocaval lymph node.

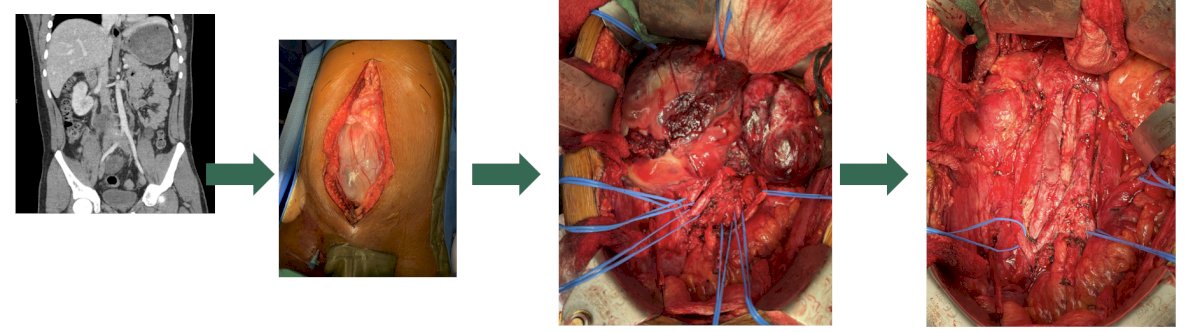

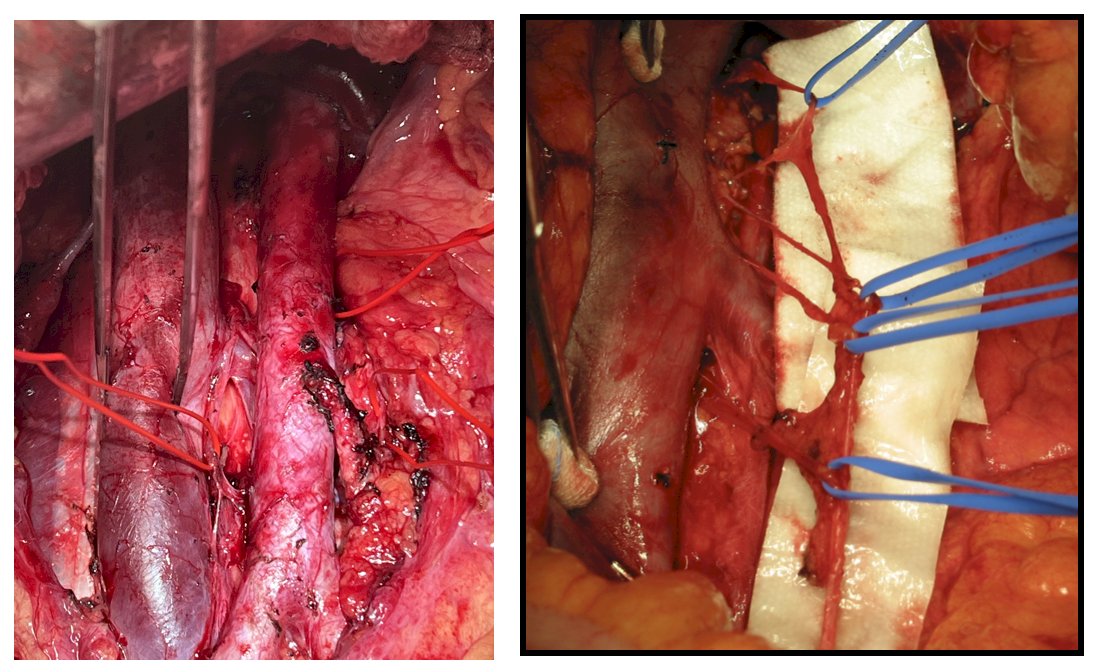

So, what is the next step? The patient ultimately underwent a bilateral template post-chemotherapy RPLND and right common and external iliac lymph node dissection. Dr. Peyton notes they used pre-surgical intravascular ultrasound to evaluate for potential invasion of the IVC and right common iliac vein, which was noted to be free of tumor invasion:

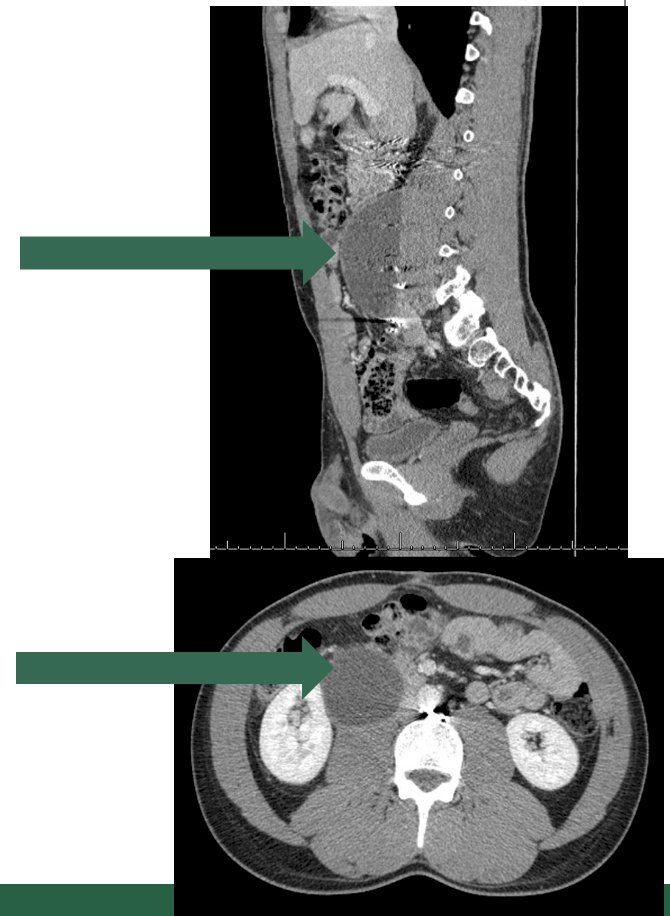

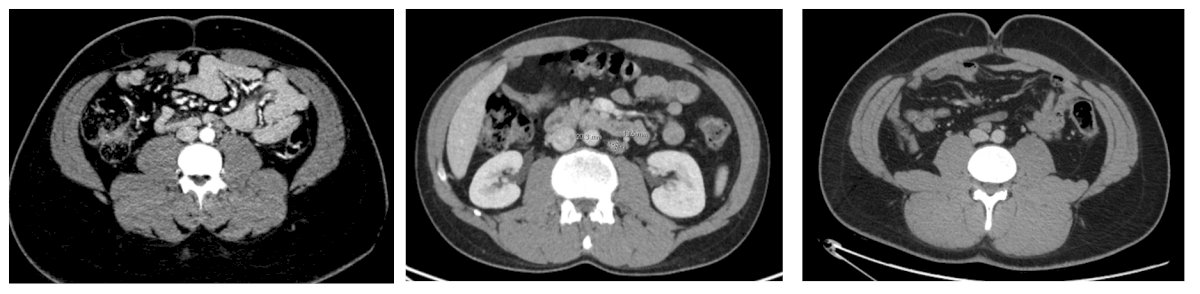

The final pathology was mature teratoma and necrosis in the periarotic lymph nodes. Two weeks post-operatively, he returned to the clinic with abdominal distention and a fluid wave on examination. A CT abdomen showed chylous ascites:

The management considerations for chylous ascites are several:

- Drain or no drain at the time of surgery?

- Repeat paracentesis?

- Diet management?

- NPO and TPN?

- Octreotide?

- IR lymphangiography?

- Shunts?

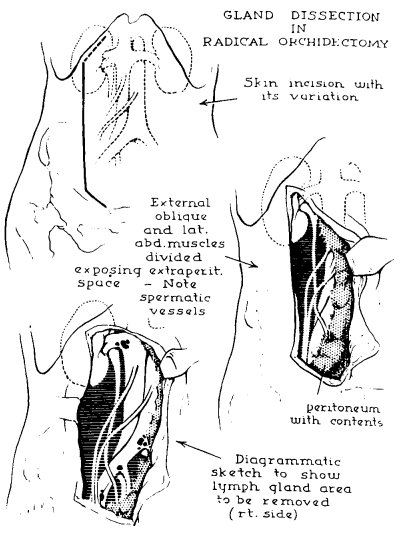

Dr. Peyton then discussed a historical perspective of RPLND, noting that there has been >100 years of RPLND for testis cancer. In 1914, Dr. Hinman noted it was the best chance for long term survival without systemic therapy:

Surgical approaches included:

- A low, paramedian extraperitoneal approach, which was associated with a limited template and potentially dangerous for supra-hilar lymph nodes

- A thoracoabdominal approach with a 10th rib to extraperitoneal, paramedian abdominal incision. This was also associated with a limited template, but wider view and better renal vascular exposure

- An anterior transabdominal approach with a laparotomy, which was a more robust approach, but increased the risk of complications (pancreatic leaks, lymph leaks, vascular injuries, ejaculatory dysfunction)

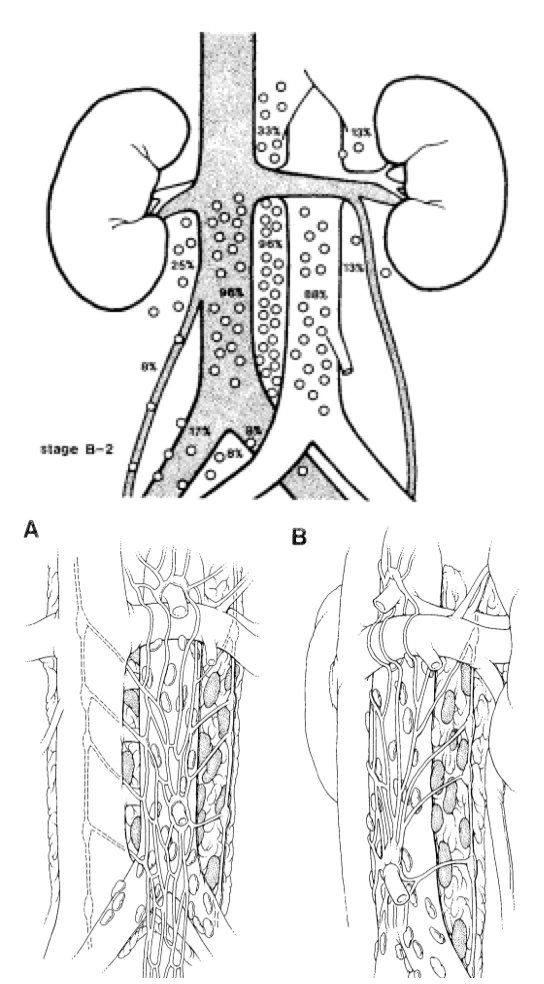

RPLND after platinum-based chemotherapy in the 1970’s significantly improved survival, but also increased hematological, pulmonary, and nutritional toxicity. RPLND complications also increased given worse toxicity from chemotherapy and reduced functional reserve. When complete responses were noted, it reduced the need for expansive complex, and morbid operations. Anatomic mapping studies in the 1980s improved our understanding of the lymph system and nodes that could be omitted from dissection (ie. supra-hilar), as well as post-ganglionic sympathetic nerve mapping:

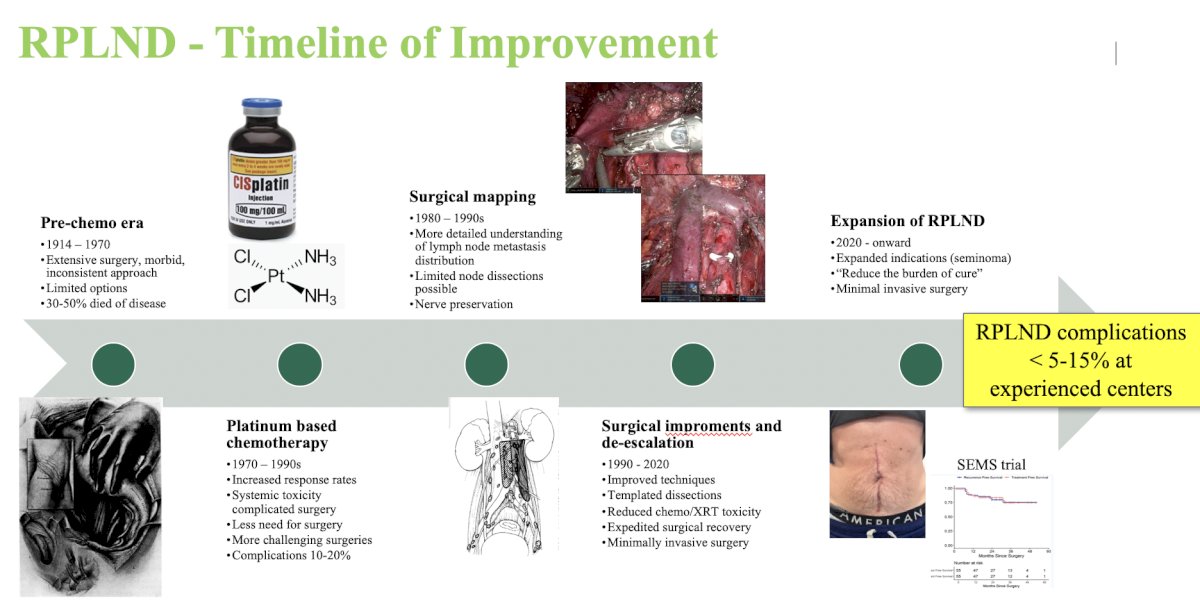

Today, there are templated dissections, expedited surgical recovery, minimally invasive surgery, and nerve preservation. The following represents an RPLND timeline of improvement:

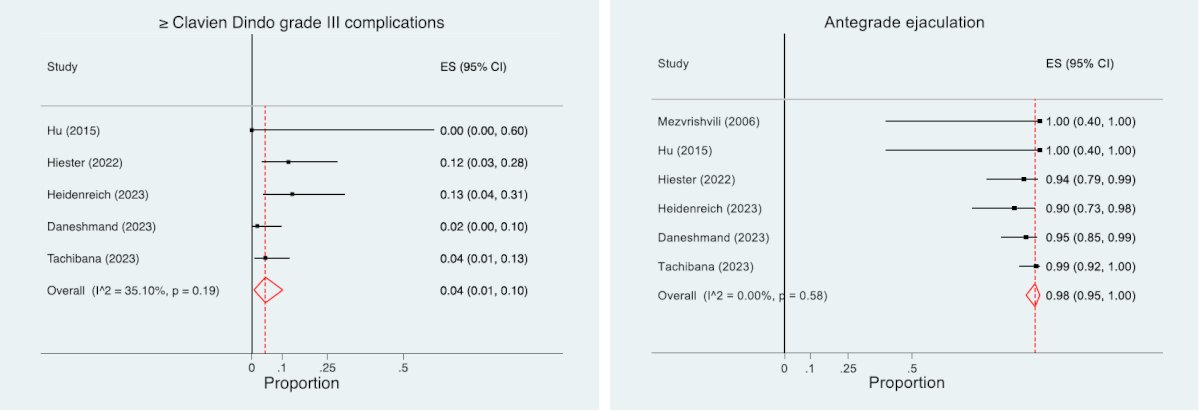

The incidence of complications is variable between the primary and post-chemotherapy setting given the desmoplastic reaction after chemotherapy and based on the residual mass size around the great vessels. Across several studies, the rate of any complication in the primary setting is <5% - 20%, and in the post-chemotherapy setting is 10 - 30%. Importantly, the incidence of complications is also related to experience. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the safety and oncologic effectiveness for primary RPLND for clinical stage II seminoma [1]. Among 8 studies and 355 patients over a median follow-up of 38 months, the rate of any complication was 1.5 – 24%, major complication rate was <5% and intraoperative complications were minimal:

For post-chemotherapy RPLND, which is technically more challenging, the complication rate may be 3-38% depending on the study and year. Factors associated with complications typically include size of the mass, additional organs resected, number of lymph nodes removed, time of surgery, and those with a seminoma component.

Dr. Peyton then discussed specific complications of RPLND, starting with vascular complications. Indeed, complexity correlates with blood loss and transfusion, given that a primary RPLND typically has an estimated blood loss is 100-200 cc and vascular injuries are typically < 2.5%. For post-chemotherapy RPLND, estimated blood loss is variable and transfusion rates are higher. Preventative measures for decreasing the risk of vascular injury include: exposure, preparedness, early proximal and distal vascular control of the great vessels, using a split and roll technique, control of the lumbar veins and arteries, and identifying sub-adventitial vessels:

With regards to thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism, these are inherent to a major abdominal surgery and a cancer diagnosis. In primary RPLND patients, the risk of a DVT or PE is ~1% and for those undergoing a post-chemotherapy RPLND, the risk is ~1-3%. Recommendations include standard preventative measures such as sequential compression devices, early ambulation, and low-molecular weight heparin. Data from NSQIP suggests that the use of chemical DVT prophylaxis increased from 5% in 2013 to 43% in 2022, with no difference in complications from prophylaxis.

Next, Dr. Peyton discussed the risk of a lymphocele, which carries a low risk, with the majority being subclinical and underreported:

The reported incidence in the literature is 1-2%, with presenting symptoms typically including retroperitoneal compressive symptoms, such as ureteral colic, lower extremity swelling, and nausea and vomiting. Preventative measures include meticulous lymphostasis during surgery, and treatment includes symptom control and observation with repeat imaging versus percutaneous drainage.

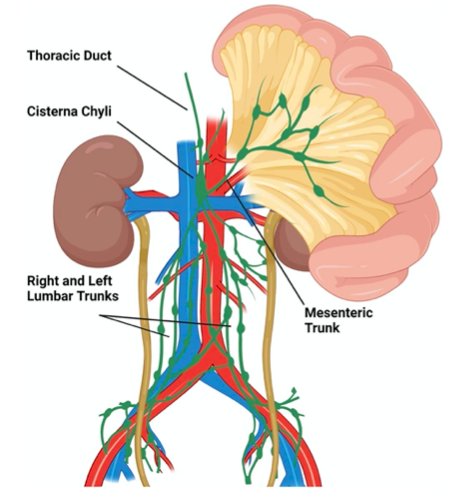

The next lymphatic complication Dr. Peyton discussed was chylous ascites, which is unique to an RPLND and includes a high volume accumulation of chylomicron-containing lymphatic fluid. The incidence in patients undergoing primary RPLND is 1-2% and for post-chemotherapy RPLND is 2-7%. Symptoms typically manifest in 2-3 weeks after surgery with abdominal distention, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and shortness of breath. The etiology is typically a disruption of the cisterna chyli and tributaries posterior to the aorta near L2:

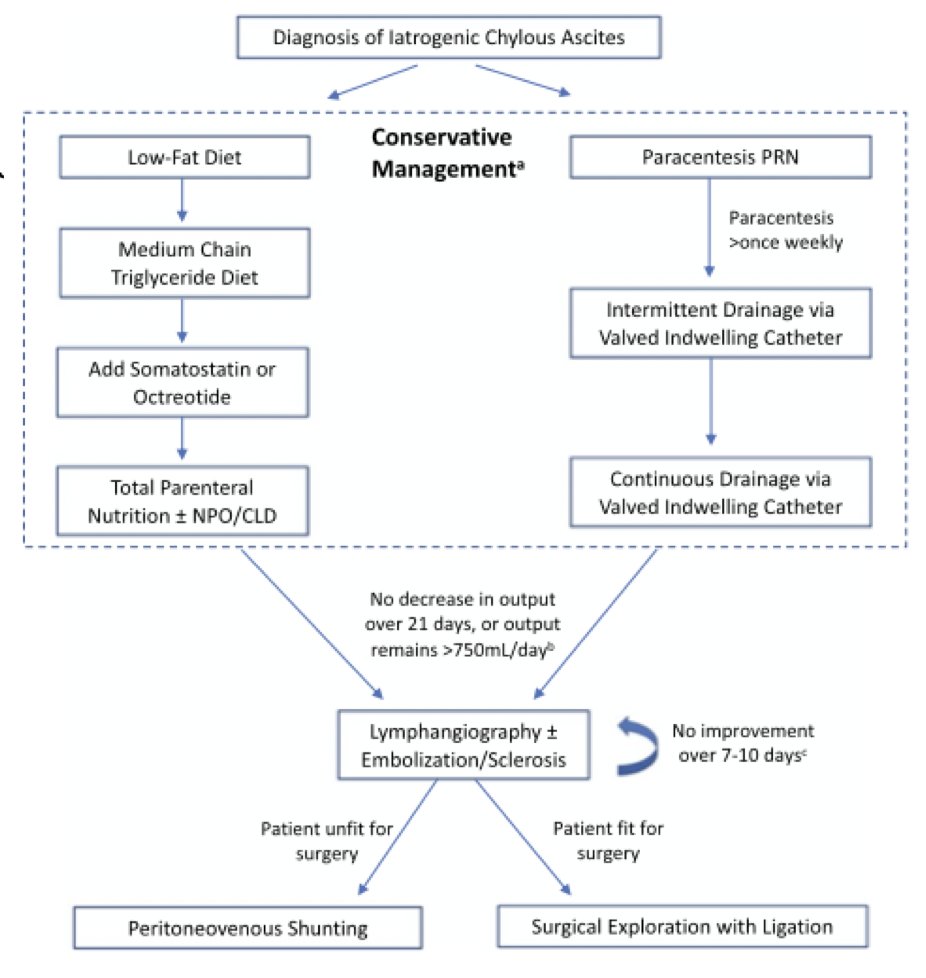

The incidence of chylous ascites is highest with IVC resection, those undergoing chemotherapy, increased operative, higher estimated blood loss, and longer operative time. Rose and colleagues [2] assessed 146 studies and 532 patients with chylous ascites in order to provide an evidence-based treatment algorithm for chylous ascites. Options include a low fat diet of medium chain triglycerides and pharmacotherapy includes somatostatin or octreotide (subcutaneous) to decrease portal pressure and enterohepatic lymph flow. Additional considerations include NPO and TPN, intermittent paracentesis as needed, and an indwelling PleurX drain for intermittent drainage, as opposed to an indwelling catheter. The treatment algorithm proposed is as follows:

Looking back at the aforementioned patient presented by Dr. Peyton, he had several paracenteses performed (~5,000 – 6,800 cc), and after a month was started on NPO + TPN + octreotide. An IR lymphangiography was performed, which showed two distinct leaks, and he was subsequently discharged home. A paracentesis 3 weeks later was < 5L and two weeks thereafter he underwent IR lymphangiography and glue to the left pelvic and other lymph channels. A month thereafter he had a resolution of his ascites, he started a low fat diet, and the TPN was stopped. Several weeks later he underwent a left neck dissection by ENT with no tumor found in five lymph nodes. Three months after that, his serum tumor markers were normal and repeat imaging showed no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease, with stable right lower lobe pulmonary nodules. Additional imaging 3 months later showed no disease in the abdomen and pelvis, with stable 10 mm pulmonary nodules (and negative serum tumor markers), however, he elected for a right sided VATS with multifocal lung wedge resection, with no malignancy identified. Imaging and tumor markers continue to remain normal and he remains today without evidence of disease.

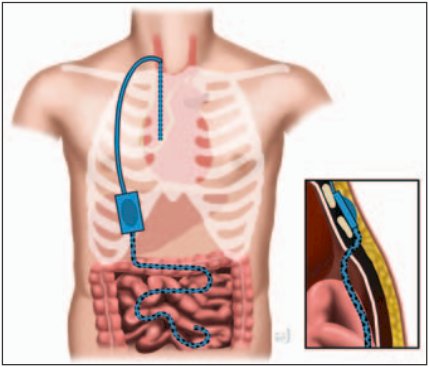

Peritovenous shunting is also an option for treatment of refractory chylous ascites. Resolution is typically 90%, but can take months to occur, and is associated with a 40% complication rate:

Surgery for chylous ascites is rarely reported, although a lymphaticovenous anastomosis has been described. This includes micro-surgery to anastomose open lymph channels to the gonadal vein (more frequently performed for lower extremity lymphedema). For surgical exploration via laparoscopy or laparotomy, the inguinal nodes can be injected with blue dye for pelvic and lumbar lymph leaks to provide intranodal lymphangiography during surgery. This may also be combined with high fat oral boluses prior to surgery whereby the leaking channels can be identified and ligated; this approach may be supplemented with fibrin glue. Of note, laparoscopically, pneumoperitoneum may limit visualization of leaking channels.

Dr. Peyton then discussed pulmonary complications, including PE, pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, which has an incidence of 1-8% after post chemotherapy RPLND. The historic risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome is secondary to bleomycin related to pulmonary fibrosis, but the incidence has declined due to improved intra- and post-operative supportive care and surgical efficiency. With regards to gastrointestinal complications, including ileus and small bowel obstruction, ileus is the most common complication, encompassing up to 45% of all complications. The overall incidence of ileus is 0-12%, with management include a nasogastric tube and decompression. The incidence of small bowel obstruction requiring operative intervention is low at <1%. Dr. Peyton notes that the routine use of an NG tube for an RLND is not necessary, with the exception of when the duodenum is resected. Of note, the extraperitoneal RPLND approach is believed to have quicker return of bowel function (1.7 vs 2.9 days).

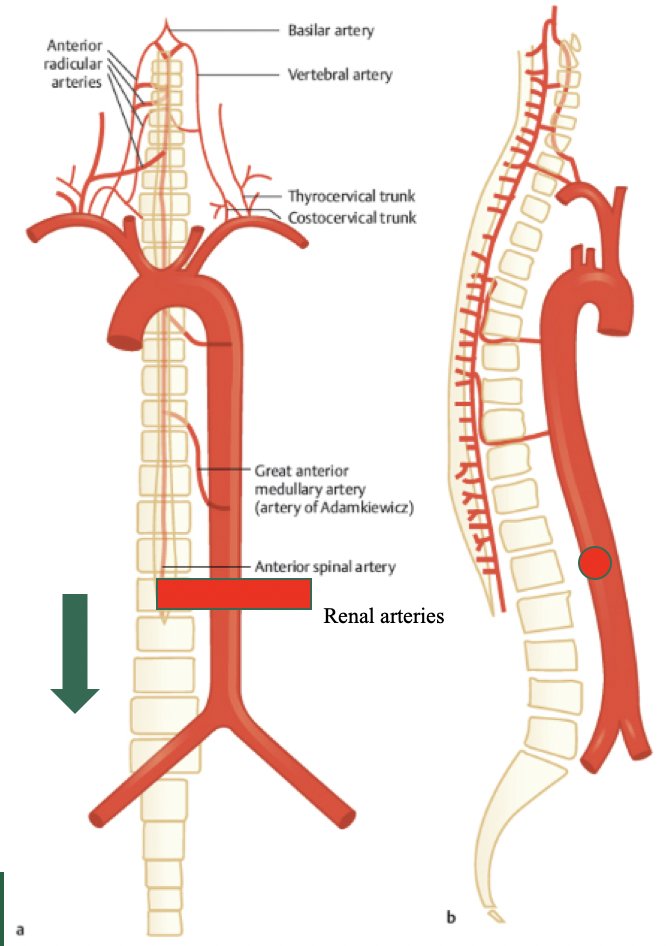

For neurologic complications, Dr. Peyton discussed neuropraxia and paralysis. Temporary neuropraxia of thigh and numbness of the anterior/medial thigh has variable low incidence but occurs with injury or resection of the anterior femoral cutaneous, genitofemoral, or ilioinguinal nerves. Typically, this resolves in several months. Spinal cord ischemia can lead to lower extremity paralysis, which is extremely rare and often is associated with combined bulky mediastinal and abdominal resections secondary to division of the lumbar and intercostal arteries. Dr. Peyton emphasized that infrarenal lumbar artery ligation is safe, as long as the subclavian and artery of Adamkiewicz are maintained:

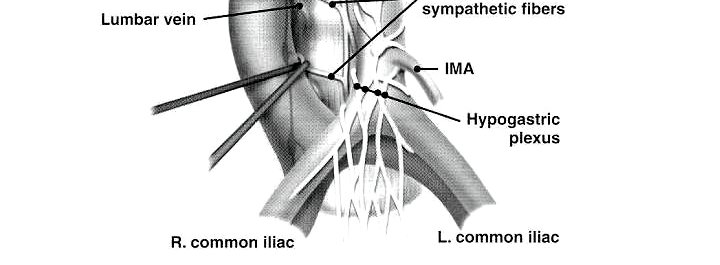

Finally, Dr. Peyton discussed ejaculatory function, with the most common complication being retrograde ejaculation secondary to disruption of the post-ganglionic sympathetic fibers between L1-L4 as they travel to the pelvic hypogastric plexus:

Preservation methods include modified template dissections in select patients and nerve sparing techniques, which are more challenging after chemotherapy:

Dr. Peyton notes that the next great debate in testis cancer is whether we see fewer complications with minimally invasive surgery: open versus robotic RPLND. Numerous studies have now been published regarding robotic RPLND, with the following outcomes:

- Intraoperative complications: 1-5%

- Postoperative complications: 5-30%

- Antegrade ejaculation: 80-95%

Dr. Peyton notes that great candidates for robotic RPLND are:

- Stage I: Primary RPLND

- Stage IIA-B: Primary RPLND

- Post-chemotherapy with small volume residual disease and small volume pre-chemotherapy

As importantly, those that are not candidates for robotic RPLND include:

- >Stage IIB

- High volume tumor bulk in the retroperitoneum

- Extensive vessel encasement/invasion

- Extensive chemotherapy response

- Dangerous tumor location

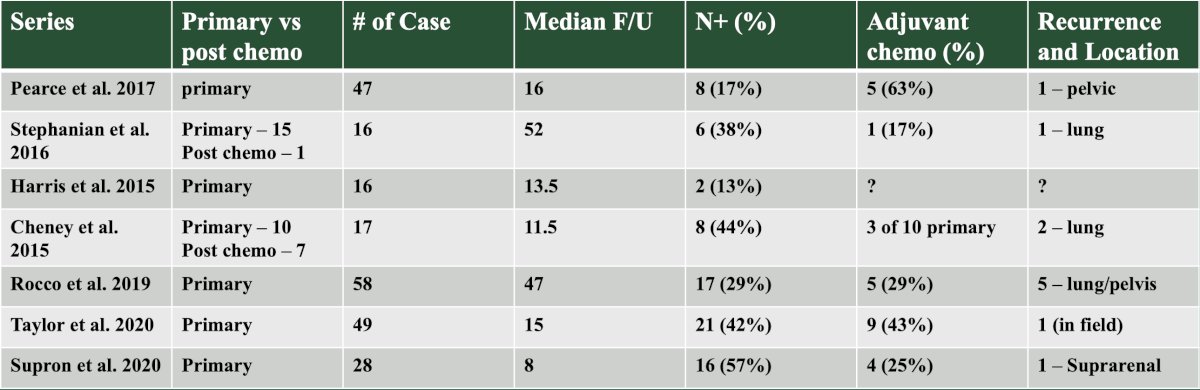

With regards to oncologic efficacy of robotic RPLND, Dr. Peyton provided the following table summarizing the available literature:

However, there may be need for caution with regards to robotic RPLND. Calaway et al. [3] reported a series of 5 patients with an unusual recurrence after robotic RPLND. This included one in-field recurrence next to an undivided lumbar vein, and four abnormal out of field recurrences in the pericolic space, peritoneal carcinomatosis, perinephric mass, and large volume liver lesions with suprahilar disease (one patient died secondary to their disease). The conclusion of these series was a cautionary tale that “although robotics is likely safe and feasible, it may expand the pool of providers willing to attempt surgery and reduce care coordination at experienced centers.” Thus, there was a call for further investigation as to the safety of robotic RPLND.

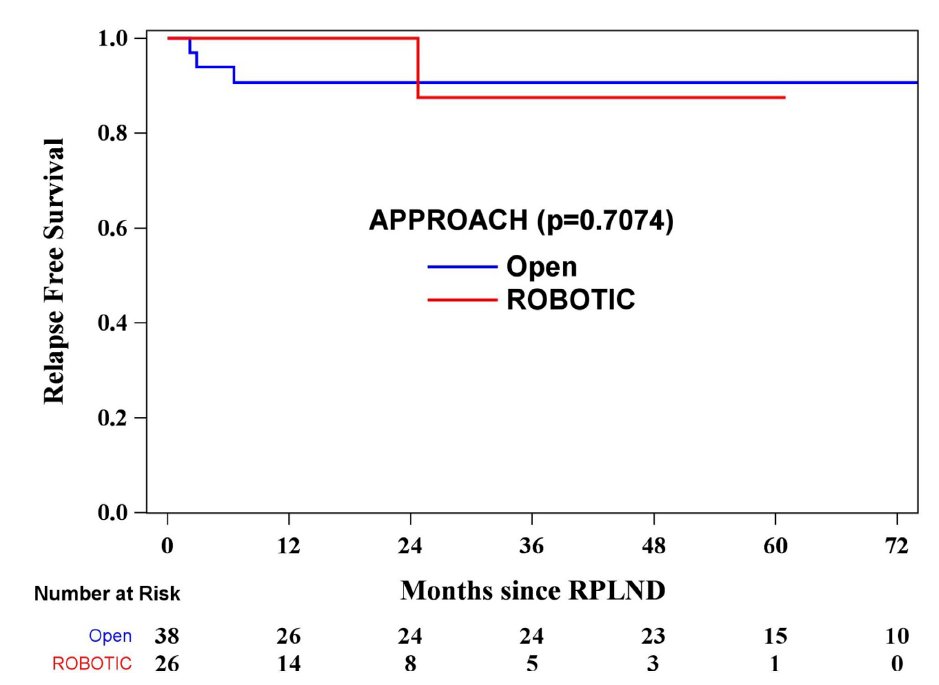

Recently, Chavarriag et al. [4] performed a propensity-matched analysis of open versus robotic primary RPLND for clinical stage II testis cancer. Among 178 patients who underwent primary RPLND, 137 were open and 41 were robotic. After propensity score matching, 26 patients in the robotic group were matched with 38 in the open group. After a median follow-up of 23.5 months (IQR 4.4-59.2), one (3.8%) relapse was noted in the robotic group compared to three (7.8%) in the open group (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.07-6.31):

No in-field relapses occurred in either cohort. A robotic RPLND was associated with a shorter length of stay (1 vs 5 days, p < 0.0001) and lower estimated blood loss (200 vs 300 ml, p = 0.032), but longer operative time (8.8 vs 4.3 hours, p < 0.0001).

Dr. Peyton concluded his presentation discussing the management of complications following RPLND with the following opinions regarding robotic versus open RPLND:

- Robotic RPLND is feasible and safe in well selected cases for experienced testis cancer surgeons with no difference in complications

- Promoting a shorter length of stay and lower blood loss for a less adequate surgery is inappropriate – node picking and relying on chemotherapy is not the answer

- Failure to cure testis cancer results in the highest life years lost, so it is crucial to perform the appropriate operation

Presented by: Charles Peyton, MD, University of Alabama-Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Associate Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Wellstar MCG Health, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2024 Southeastern Section of the American Urological Association (SESAUA) Annual Meeting, Austin, TX, Wed, Mar 20 – Sat, Mar 23, 2024.

References:

- Parizi MK, Margulis V, Bagrodia A, et al. Primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage II seminoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and oncological effectiveness. Urol Oncol. 2024 Apr;42(4):102-109.

- Rose KM, Huelster HL, Roberts EC, et al. Contemporary Management of Chylous Ascites after Retroperitoneal Surgery: Development of an Evidence-Based Treatment Algorithm. J Urol. 2022 Jul;208(1):53-61.

- Calaway AC, Einhorn LH, Masterson TA, et al. Adverse Surgical Outcomes Associated with Robotic Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection Among Patients with Testicular Cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76:607-609.

- Chavarriaga J, Atenafu EG, Mousa A, et al. Propensity-matched Analysis of Open Versus Robotic Primary Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection for Clinical Stage II Testicular Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024 Jan 25 [Epub ahead of print].