(UroToday.com) The Earlier Treatment in Prostate Cancer “How can we maximize the therapeutic index?” educational session at the European Society of Medical Oncology’s (ESMO) 2021 congress included a presentation by Dr. Piet Ost discussing the role of imaging in selecting treatment. Dr. Ost notes that it is important to highlight that the Will Rogers phenomenon is present in prostate cancer. For example, high-risk localized prostate cancer patients that are negative with conventional imaging will have a proportion of patients that will be PET/CT positive and move to the oligometastatic cohort of patients. Thus, this shift will improve outcomes of the localized high-risk patients by removing those that are truly oligometastatic, but also improving outcomes of metastatic patients by adding low-volume oligometastatic patients to this group. As such, these are artificial improvements in outcomes-based novel imaging leading to stage migration.

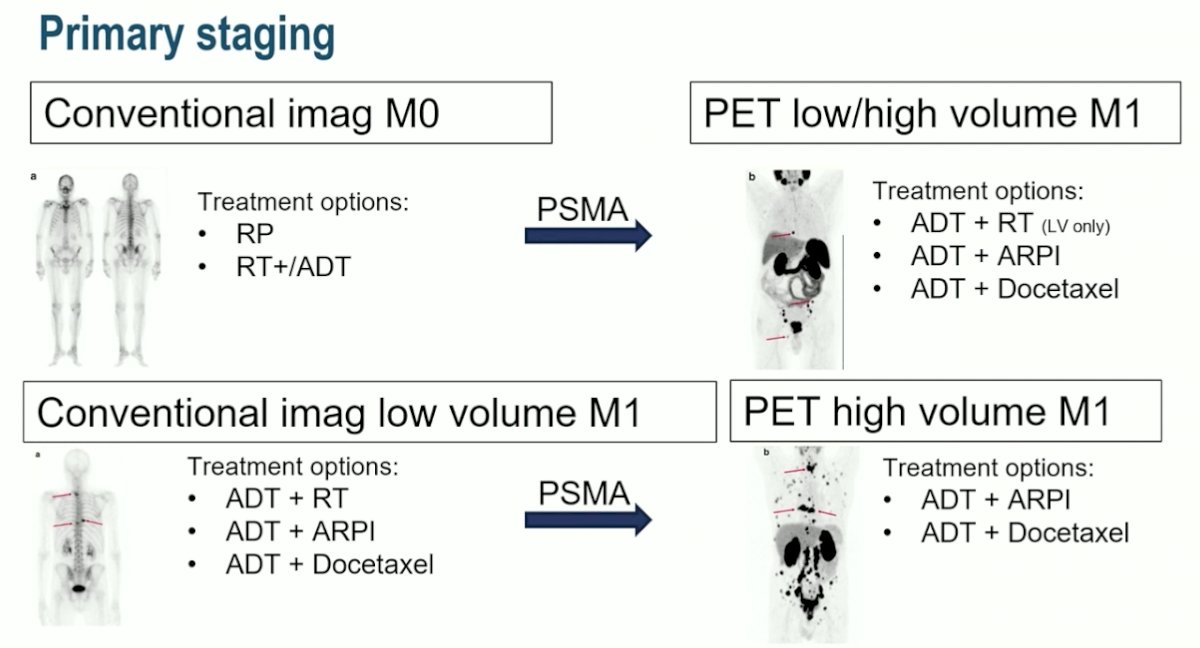

Dr. Ost notes that two important general concepts of treating prostate cancer are that all treatment concepts are based on trials and their eligibility criteria and that all trials use conventional imaging. This has implications for PSMA PET whereby imaging these patients may change their treatment options and clinical trial eligibility:

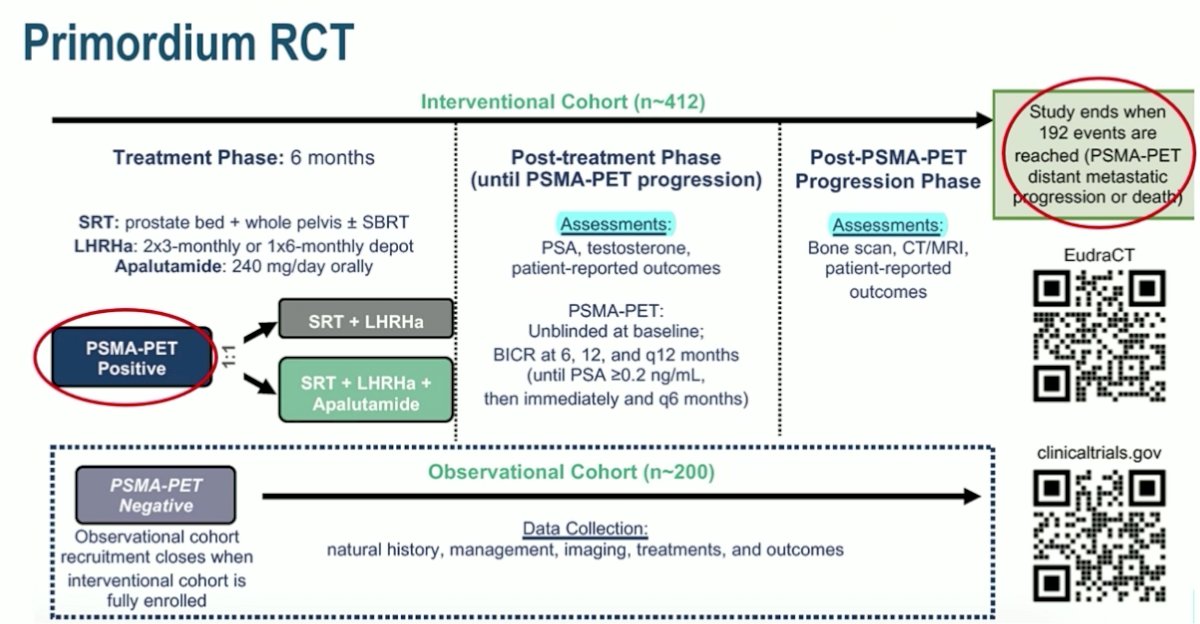

Dr. Ost’s suggestion for assessing treatment selection based on PSMA imaging is a randomized clinical trial, with the hypothesis being that treatment selection based on PSMA is better than conventional imaging. His proposed clinical trial schema is outlined as follows:

Dr. Ost emphasizes that there is a potential role for PSMA pre-salvage radiotherapy. Among patients in the GETUG-16 trial, the 5-year biochemical recurrence-free survival is 60-80% suggesting that 20-40% may also have distant disease. The ideal situation is that among patients being considered for salvage radiotherapy, all would receive a PSMA PET/CT to identify those that need treatment (de-)intensification and thus improving outcomes and decreasing toxicity. Importantly, in the GETUG-16 trial, the 5-year prostate cancer-specific survival rate was 99%, so Dr. Ost states that even if all patients were to have a PSMA PET/CT before starting salvage therapy to help guide treatment, there is no way to improve on already excellent prostate cancer-specific survival rate. Dr. Ost suggests that we are unlikely as a community to wait for the data given that follow-up time will be many years to show an improvement in downstream outcomes. This is also clear by the evolution of the EAU guidelines, noting that before 2010 the recommendation was for a bone scan/CT scan for a PSA >10 ng/mL, after 2010 a choline PET-CT for PSA >1 ng/mL, and now after 2016 a PSMA PET-CT for PSA <0.5 ng/mL:

Dr. Ost suggests that doing PSMA PET-CTs for patients with PSAs <0.5 ng/mL is too early, unlikely to change the disease course, and likely to create confusion. For example, for patients with a negative PET, should patients have salvage radiotherapy alone without ADT? Should we observe the patient? For those with a positive PET inside the pelvis that is going to undergo salvage radiotherapy, should the field of treatment be adapted? What becomes an even larger issue is if the positive PET/CT scan is outside the pelvis, with several potential options:

- Abandon salvage radiotherapy or proceed? STAMPEDE indicates that local therapy remains important for low volume disease, so maybe we still have to optimize local control and deliver salvage radiotherapy

- Metastasis directed therapy: there is only phase 2 data indicating that MDT improves PFS

- Intensifying systemic therapy: however, the 5-year OS rate is already 99%, is an improvement in MFS good enough? If one were to treat with ADT + chemotherapy + a second-generation antiandrogen receptor inhibitor (extrapolating from LATITUDE and STAMPEDE), perhaps there is risk of overtreatment for these patients

The ideal answer is to perform a randomized clinical trial, with one of several examples being the Primordium trial, assessing PSMA PET/CT for eligibility, as well as using PSMA PET/CT for surveillance:

With regards to nmCRPC, patients that were included in the key clinical trials were all imaged with conventional imaging, thus it is likely with PSMA PET/CT imaging that this disease space is shrinking. Fendler et al.1 suggested that 98% of patients deemed nmCRPC on conventional imaging were PSMA PET-positive with the following breakdown of disease location and treatment options:

The standard of care for both nmCRPC and mCRPC is virtually the same, but we lose the option of apalutamide and darolutamide with upstaging. There are no data to suggest that patients with a positive PSMA result should not be treated with enzalutamide/apalutamide/darolutamide, even if they have M1 disease on PSMA. A key trial in this disease space is the DECREASE trial, which will further triage nmCRPC patients for appropriate therapy based on PSMA PET imaging, including utilization of darolutamide:

Dr. Ost concluded his presentation of the role of imaging in selecting patients with the following take-home messages:

- PSMA PET might artificially improve outcomes, but it may result in both over and under treatment

- Use conventional imaging to decide on the standard of care treatment

- Only use PET in the setting of biochemical recurrence following salvage radiotherapy

Presented by: Piet Ost, MD, PhD, Department of Radiation Oncology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Congress 2021, Thursday, Sep 16, 2021 – Tuesday, Sep 21, 2021.

References: