San Francisco, CA (UroToday.com) In this panel discussion led by Drs. Kleutz and Morgans, with open discussion by the entire panel consisting of members of the genitourinary oncology group at the US FDA, a discussion was had surrounding the development of the metastasis-free survival endpoint and its use in the three trials that have led to drug approval for non-metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC)

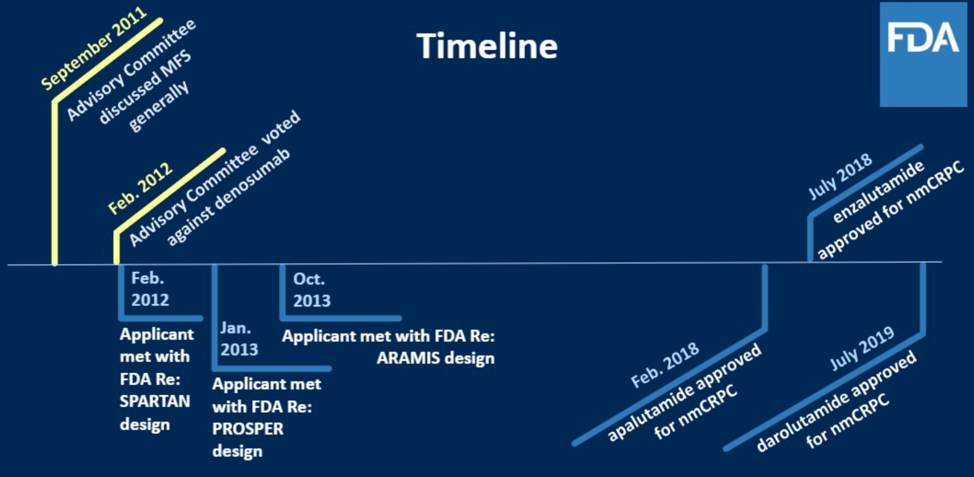

The timeline discussed by the panel is shown below.

In 2011, there was interest in evaluating multiple new anti-androgen therapies earlier in the disease course of advanced prostate cancer. Previously, the standard endpoints for evaluating the efficacy of drugs in this space were overall survival as well as patient reported pain. To get feedback from the clinical oncologic community on how to think about appropriate endpoints, the FDA convened an oncology drug advisory meeting (ODAC). These meetings are held typically to either (1) get feedback from the oncologic community on the risk/benefit of a specific product or (2) discuss a drug development challenge such as redefining endpoints.

Dr. Kleutz drew from specific quotes from experts present at that meeting to illustrate how the attendees at the meeting had detailed discussion about the patient population affected by non-metastatic disease, what their symptoms were, what defined high-risk patients within that subgroup, and what endpoints within what time frame would be meaningful for these patients. To this last point, it was felt that a clinical change that would lead to either new significant symptoms outweighed by side effects of the drug, new therapies, or accelerated clinical course were reasonable thresholds for regulatory approval.

Out of the discussion at the ODAC, the surrogate endpoint (surrogate for overall survival) of metastasis-free survival was created. This was defined as time from randomization to death or first evidence of extra-pelvic radiographically evident bone or soft tissue metastasis as decided by blinded central independent review. There was much debate about whether local progression should be included, but ultimately it was felt that local progression would increase the number of events without necessarily reflecting accelerated clinical course or significant symptoms. MFS was subsequently used for the SPARTAN, ARAMIS, and PROSPER trials in the non-metastatic castration resistant clinical space. Interestingly, during this time, denosumab was submitted for approval in this same clinical space based on data showing a 15% risk reduction (median time to bone metastasis increased from 25.2 months to 29.5 months) for developing bone metastasis. Approval here was rejected by FDA given the ~5% risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw and concerns about giving this drug longer term and thus increasing the risk of ONJ.

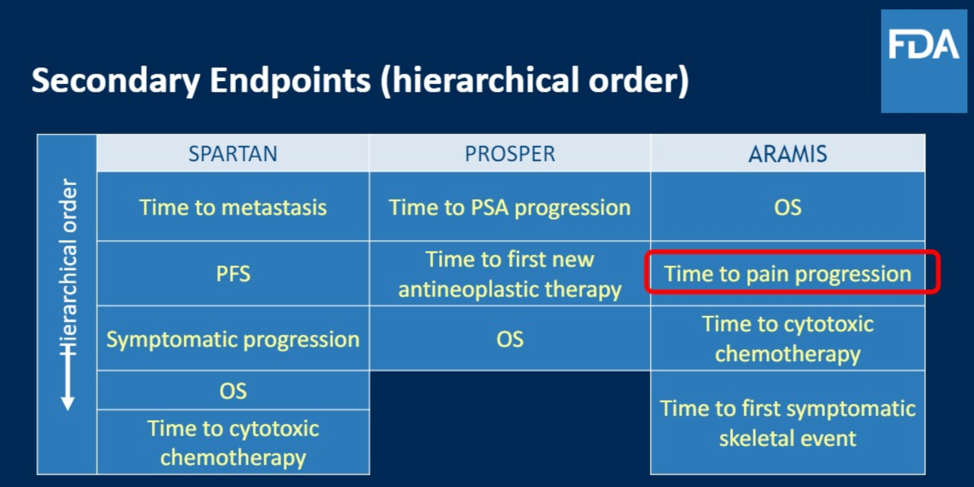

There was also extensive discussion of secondary endpoints during the design of these trials. These were instituted in a variable fashion by the sponsors of each trial, with a summary shown below. The selection of secondary endpoints can be challenging, especially when using a new primary endpoint, because you have to appropriately power your study to detect outcomes.

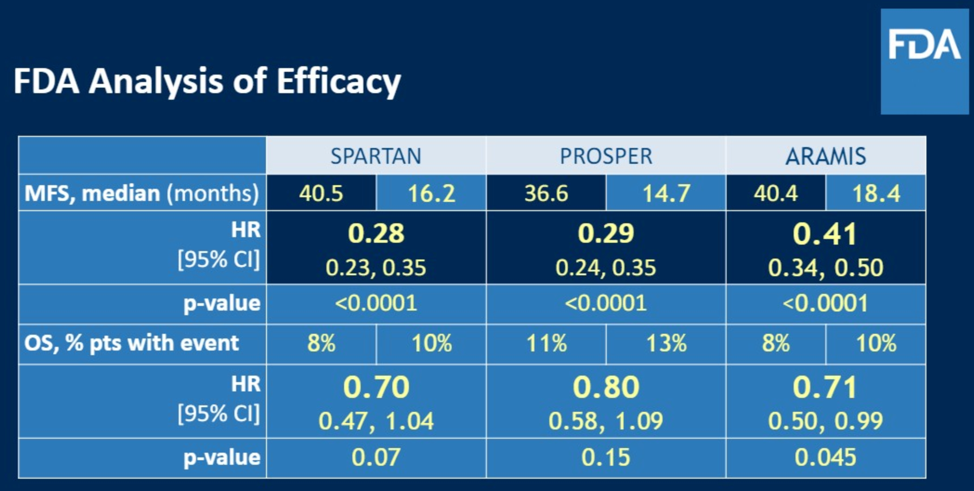

The panel then discussed that although these trials all showed signal towards improved MFS, approval for these agents were based on an overall survey of the trial results, including numerical trends favoring overall survival for the studied interventions. The number of events required to analyze overall survival had not been reached at the time where there was clear MFS improvement. Indeed, overall survival remains critically important. In its guidelines to industry sponsors for trials including MFS as an endpoint, the FDA mandates two things: (1) At the time of final analysis of MFS, an overall survival analysis is required and should show numerical trend towards favorability and (2) The FDA expects continued follow-up to confirm overall survival data. The FDA analysis of efficacy for each of the trials in the non-metastatic CRPC space are shown from the time of approval.

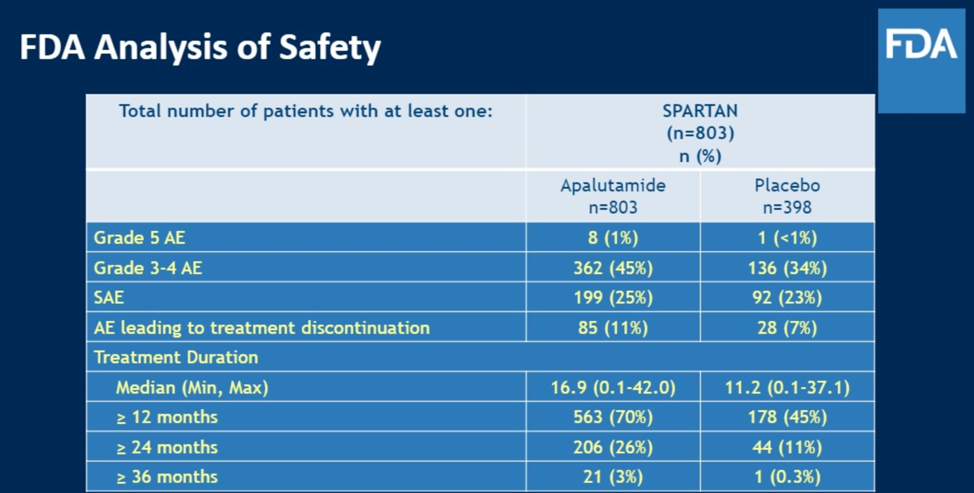

The panelists also discussed the obvious importance of safety analysis, perhaps even more important in the non-metastatic setting because patients are otherwise relatively asymptomatic and so it was critical to ensure safety in the intervention arm. After seeing such as that shown below for SPARTAN, the FDA was much more reassured that the intervention was both effective and reasonably safe.

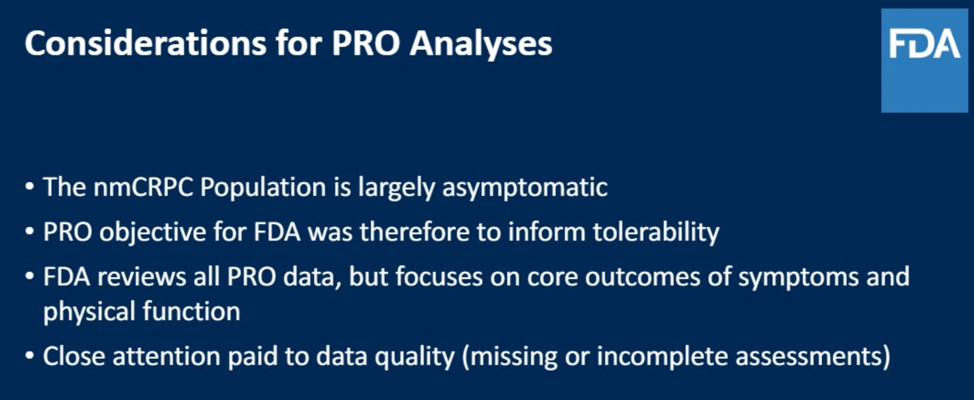

Along with Dr. Morgans, there was then a discussion of patient reported outcomes (PRO). The panelists commented that they tend to focus more on core outcomes of symptom reporting and physical function as these are viewed as relatively less subjective. The considerations for PRO analysis are shown below. The panelists noted that over the past several years, reporting rates of PRO have improved significantly.

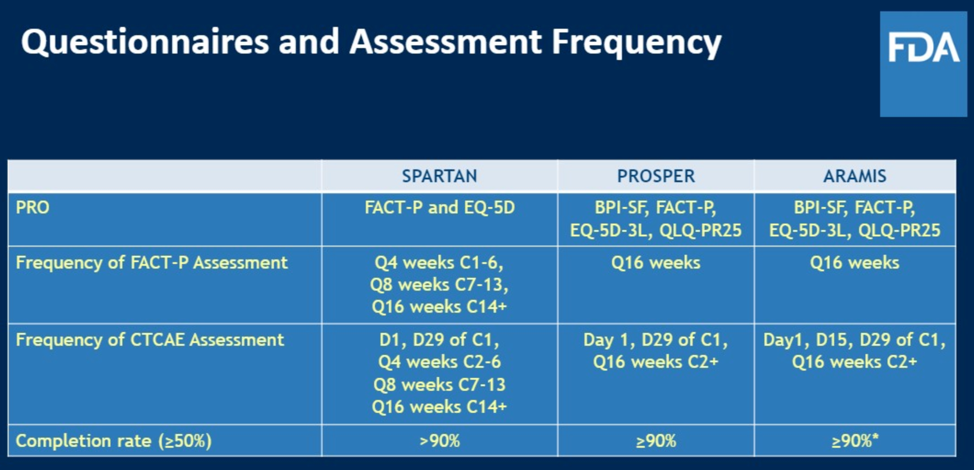

The PRO assessments used in each of the nmCRPC trials are shown below. As can be seen, there were many different questionnaires used, and in total this represented a significant amount of work that the patients enrolled had to undertake somewhat frequently.

Dr. Morgans noted that there are likely overlapping domains covered by these questionnaires, and the FDA panelists agreed with the comment that they are working to narrow down questionnaires to optimally and efficiently capture patient reported outcomes efficiently. One example of how they are trying to narrow down questionnaires is limiting the ways sexual function is assessed, as this patient population is undergoing continuous testosterone suppression and the interventions being tested are not likely to improve sexual function.

The panel then discussed how trialists can get guidance from the FDA regarding how to approach PROs. There is actually a group at the FDA that one may consult with either in the form of an IND-type meeting or by a submission that receives only a written response.

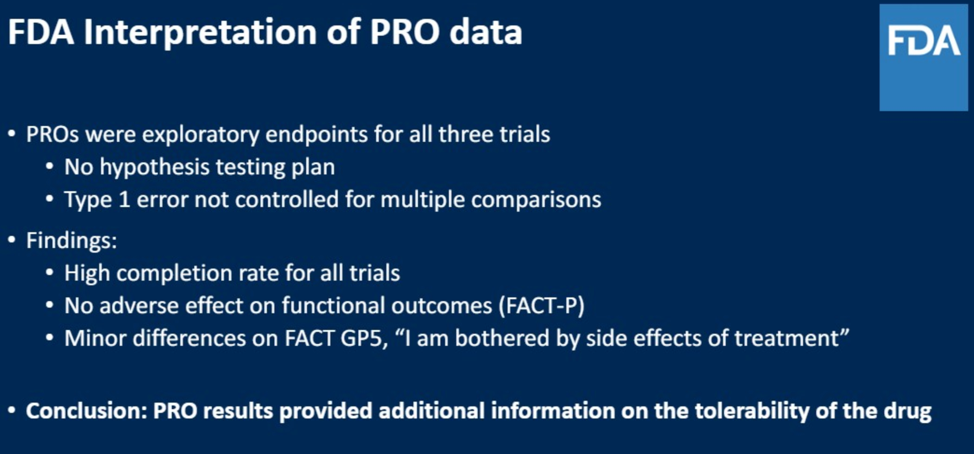

A summary of how the FDA utilized PRO data in the nmCRPC trials is shown here:

After the initial discussion, there were many interesting questions, some of which are summarized here.

How does the panel anticipate novel imaging findings such as PSMA-PET impacting the use of surrogate endpoints such as MFS? This remains to be seen as the original endpoint was defined to reflect a point where patient symptoms and treatment change. Since it is unclear still how identifying asymptomatic metastatic disease that was otherwise not visible on conventional imaging will impact patient care, only time will tell how the MFS endpoint will need to be adapted.

Will PSA or some PSA property such as doubling time ever become a regulatory endpoint?

The data on PSA as an endpoint is mixed. It seems to be decent when examining the efficacy of androgen-targeting agents potentially, however it is not as useful for alternative therapies like Provenge or Radium. PSA, like MFS, would be a surrogate endpoint, but would be one step removed from things that impact clinical course since treatment is not often changed in the advanced disease setting only based on PSA level. PSA may have more of a role to play as a surrogate endpoint for drug approval in earlier disease settings such as biochemical recurrent, but it would still likely need to be associated with other clinically important surrogate outcomes.

How are PROs weighed along with adverse event data?

Patient reported outcomes on tolerability are a different readout of adverse events. For example, you won’t often see symptomatic bone marrow suppression, but this is an important adverse event that needs to be identified. The panel also noted that not all PROs that are requested by the FDA reflect what clinicians administering the drug may want to know for their practice. For example, a questionnaire may have a ceiling effect on its ability to measure specific outcomes, and so it may be prudent in trial design to include alternative PROs.

How do you consider PFS2 as an endpoint?

For the nmCRPC trials, PFS2 was viewed as a sort of safety endpoint. There was initial worry that if you used potent anti-androgen therapies earlier in the disease course, you may reduce the effectiveness of subsequent therapies. Fortunately, the PFS2 data did not support that worry, which was reassuring.

What other regulatory endpoints are to come?

Other regulatory endpoints that have been used are radiographic progression free survival, though like with MFS it is helpful and important to have other surrogate endpoints to tell a story in total about the efficacy of the drug. The panelists gave credit to the Prostate Cancer Working Group regarding input on how to best define radiographic progression free survival.

What is the role of the FDA in asserting what the control arm in a trial should be?

The regulatory framework that the FDA works within suggests that a drug must be safe and effective for the indication it is seeking. At the current time, the FDA does not have a comparative efficacy framework, and can only really mandate specific comparators if there is an overt safety reason with the control arm. It seemed from this discussion that this would need to be addressed at a higher level, perhaps by legislation.

Presented by:

Alicia Morgans, MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Hematology/Oncology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois

Paul Kleutz, MD, US Food and Drug Administration

Jamie Brewer, MD, US Food and Drug Administration

Elaine Chang, MD, US Food and Drug Administration

Daniel Suzman, MD, US Food and Drug Administration