Dr. Mahal began by reviewing the case initially presented in this session by Dr. Carthon. To recall, this was an 81-year-old man with a history of Gleason 4+3=7 prostate cancer who was initially diagnosed in 2005 as a result of urinary symptoms, without PSA screening. He declined surgery at the time of diagnosis and stopped radiotherapy after a single fraction and further deferred any additional therapy due to concerns regarding side effects and travel. For many years, he had no prostate cancer follow-up. More recently, he was admitted to the hospital as a result of confusion and was diagnosed with both sepsis and also widespread metastatic prostate cancer. Dr. Mahal focused, in particular, on the importance of genomics in this gentleman’s care.

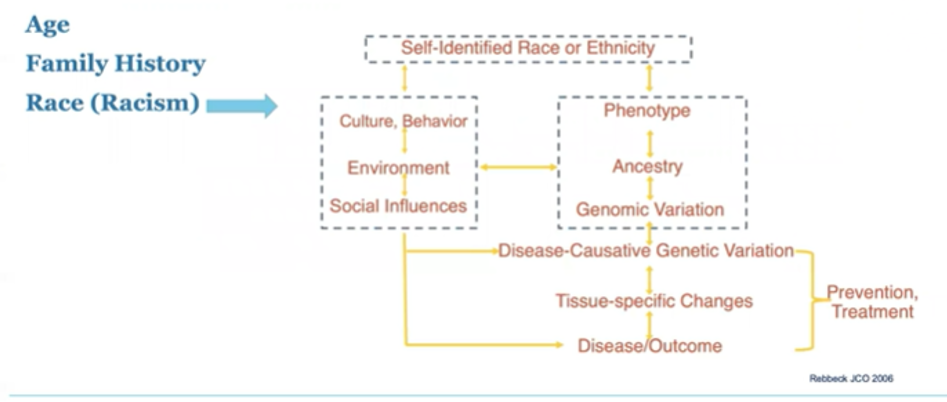

He began by emphasizing that there are three well-established risk factors for prostate cancer: age, family history, and race. However, he emphasized that the social construct of race is not monolithic and has a complex interplay in determining disease-causative genetic variation, tissue-specific changes, and disease outcomes.

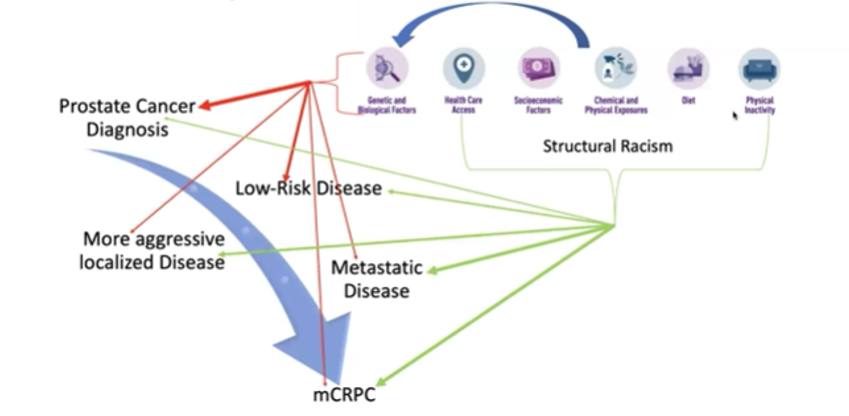

He emphasized that Black men have both a higher lifetime prevalence of prostate cancer (18% vs 13% in white men) and a higher lifetime probability of dying of prostate cancer (4.4% vs 2.4%). Thus, given the 4800 Black men who die of prostate cancer in the US annually, more than 2500 of these can be considered disparate, or excess, compared to white men.

Further, trends in precision medicine may actually exacerbate disparities. With an increasing push for genomic studies, European men are dramatically overrepresented, an issue that is increasing over time. Currently, nearly four-fifths of participants in GWAS studies are of European descent despite making up only 16% of the population.

Thus, the lack of representative studies has the potential to worse disparities given that risk stratification approaches, and potential therapies, are being developed on the basis of these genomic data. He further highlighted that, in the TCGA, there are insufficient samples from Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and American Indian populations to detect a mutation with 10% frequency. Not surprisingly, white individuals are over-represented in the dataset.

Among more than 700 cancer loci identified, he highlighted that more than 80% of these have been first discovered in Whites and approximately 1% among African and Latin American populations.

When we focus on prostate cancer, Dr. Mahal focused on a few examples that highlighted representative samples. In a recent analysis of the genomic landscape of prostatectomy specimens, Dr. Spratt presented data at ASTRO which included nearly 2000 Black men among the 17,000 patients who underwent prostatectomy in the cohort. They found that a disproportionate number of Black men have low androgen-receptor activity in their tumors. This has potential implications for treatment decision-making and their response to androgen deprivation. Further, this work demonstrated that Black men have distinct cancer hallmark gene expression, with lower expression of pathways including DNA repair, cell cycle, and metabolism but increased immune-related pathways.

Additionally, based on those data, it was predicted that Black men would be more likely to have radiosensitive tumors, though the underlying causes are unclear.

Examining genomic risk across race and Gleason score among those who had undergoing prostatectomy (n=1240, Black men n=286), Dr. Mahal highlighted some of the work he had led demonstrating that among patients with low-grade disease (Gleason 6), a greater proportion of Black men had intermediate to high genomic risk, than white men. There were no meaningful differences among patients with higher-grade histology.

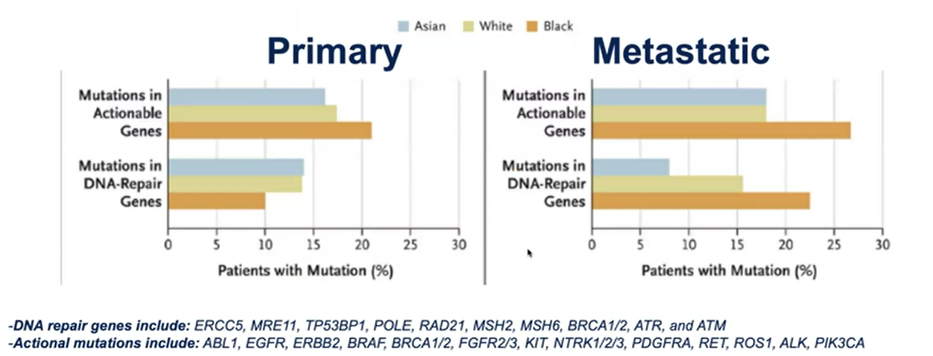

Building on this work, he examined patients from 2393 men, focusing on 474 genes across race and stage of the disease. They found that, in the metastatic setting, Black men were more likely to have AR mutations. Again focusing on the metastatic setting, he emphasized that Black men were more likely to harbor actionable mutations.

He emphasized that this study is limited by the small sample size as well as lack of information of when testing was performed during the natural history of disease and of treatments administered. Building on this, he highlighted data from Foundation Medicine which demonstrates that, overall, men of African and European ancestry have similar patterns of targetable gene alterations. Rather than prior work that depends on self-reported race, this was an ancestry-based analysis. Linkage to treatment data highlighted that men of African ancestry undergoing genetic testing later in their disease course. However, the proportion of patients who receive immunotherapy or PARP inhibitors did not differ significantly on the basis of ancestry. However, men with African ancestry were much less likely to be enrolled in clinical trials (11% compared to 30% in men of European ancestry) – an effect that was present both in academic centers (40% vs 57%) and in the community setting (8.7% vs 15%).

Circling back to the initial case example, Dr. Mahal suggested that initial upfront genetic testing may have been able to identify aggressive disease early to change disease trajectory.

Dr. Mahal then addressed the broad question of why there are racial disparities in prostate cancer, emphasizing the range of underlying issues including access to care, differential exposures, socioeconomic factors, and others. Many of these may act through the genetics and biology of tumors to influence treatment outcomes.

He highlighted many ongoing unanswered questions including health system factors, genetic susceptibility, social factors, tumor-related factors, and the interactions between genes and the environment which may contribute to the biological implications of racism. To address this involves a “trans-disciplinary” approach to research. Further trials are needed in diverse populations.

Presented by: Brandon Mahal, MD, University of Miami Health System, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Miami, Fl

Written by: Christopher J.D. Wallis, Urologic Oncology Fellow, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Twitter: @WallisCJD at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, #ASCO21, June, 4-8, 2021