(UroToday.com) The 2022 Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) Hybrid Meeting included a session on the importance of lifestyle and prevention of complications in advanced prostate cancer and a presentation by Dr. Charles Ryan discussing how we should take care of our patient’s brain and mood. Dr. Ryan started by defining the brain as an organ with a plethora of androgen receptors, which may be impacted by the treatments we prescribe our patients, as well as defining ‘mood’ as a mental health impact of being an advanced prostate cancer patient.

It is important to recognize that men are a mental health population that is high risk for depression/suicide, and having a diagnosis of cancer increases this risk. Furthermore, ADT compounds the risk of mental health effects in this already high risk population. Certainly, the causes of depression are multifactorial, which is no different in our prostate cancer patients. This often includes biological variables, psychological variables, and social variables,1 as highlighted in the following schematic:

With regards to screening for depression, the NCCN offers general screening recommendations for depression and for the impact of mood symptoms on functioning. Effective treatments for depression should be considered for our prostate cancer patients, including exercise, counseling, and pharmacologic strategies. There is no screening tool specifically recommended for cognitive decline for this patient population, however, referral to a specialist is recommended for depression and/or cognitive assessment and intervention. As follows are several screening questions provided by the NCCN Survivorship guidelines that can be asked at regular intervals, especially when there is a change in clinical status or treatment:

Based on the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 recommendations, Dr. Ryan highlighted that the following points should be kept in mind when diagnosing major depressive disorder:

- Depressed mood

- Decreased interest or pleasure in activities

- Changes in weight or appetite (increase or decrease)

- Changes in sleep patterns (increase or decrease)

- Psychomotor retardation or agitation

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of guilt/worthlessness

- Changes in cognition (decreased concentration/indecisiveness)

- Suicidal ideation

A diagnosis of major depressive disorder can be established if: >= 5 criteria are met, including at least one of #1 or #2 being present during the same 2 week period, leading to significant distress or representing a change from previous functioning.

Dr. Ryan notes that depression is associated with worse outcomes in prostate cancer patients. Highlighting data from the SEER-Medicare population in the US,2 depressive symptoms were associated with a lower likelihood of choosing treatment (ie. radical prostatectomy) and worse overall survival among men with localized prostate cancer. Specifically, men with depression had a 23% to 32% decreased likelihood of choosing definitive therapy across risk groups for localized disease:

A very practical way for clinicians to diagnose depression in their prostate cancer patients is to use the Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool:

Based on the PHQ-9 results, treatment is recommended for those patients with a score of >= 8.1 There are several studies highlighting ways to treat depression in cancer patients, and Dr. Ryan highlighted one study that used the psychedelic substance psilocybin, which was assessed in a randomized double-blinded clinical trial.3 In this trial, 51 cancer patients with life-threatening diagnoses and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety were randomized to a very low (placebo-like) dose (1 or 3 mg/70 kg) versus a high dose (22 or 30 mg/70 kg) of psilocybin. High-dose psilocybin produced large decreases in clinician- and self-rated measures of depressed mood and anxiety, along with increases in quality of life, life meaning, and optimism, and decreases in death anxiety. At 6-month follow-up, these changes were sustained, with 80% of participants continuing to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety.

Dr. Ryan then discussed the effects of low testosterone on the brain. We already know that testosterone crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts on androgen receptors in the hippocampus and amygdala. This provides the function of learning and memory, and thus testosterone may have a protective effect in preventing cognitive decline. Previous studies have shown that low levels of testosterone are associated with poorer visual and verbal memory. Possible mechanisms for how androgens are neuro-protective include (i) increasing neuronal viability, (ii) decreasing beta-amyloid levels, and (iii) decreasing tau hyperphosphorylation. Dr. Ryan also emphasized that it is well known that DHT and testosterone both decline with age, particularly after the age of 50 years old.

Previous work from Gonzalez et al.4 has shown that even as little as 6-12 months of ADT may lead to modest cognitive decline. In this study of 84 men undergoing radical prostatectomy subsequently treated with ADT and 88 men without prostate cancer (control group), ADT recipients were more likely to demonstrate impaired performance within 6 and 12 months:

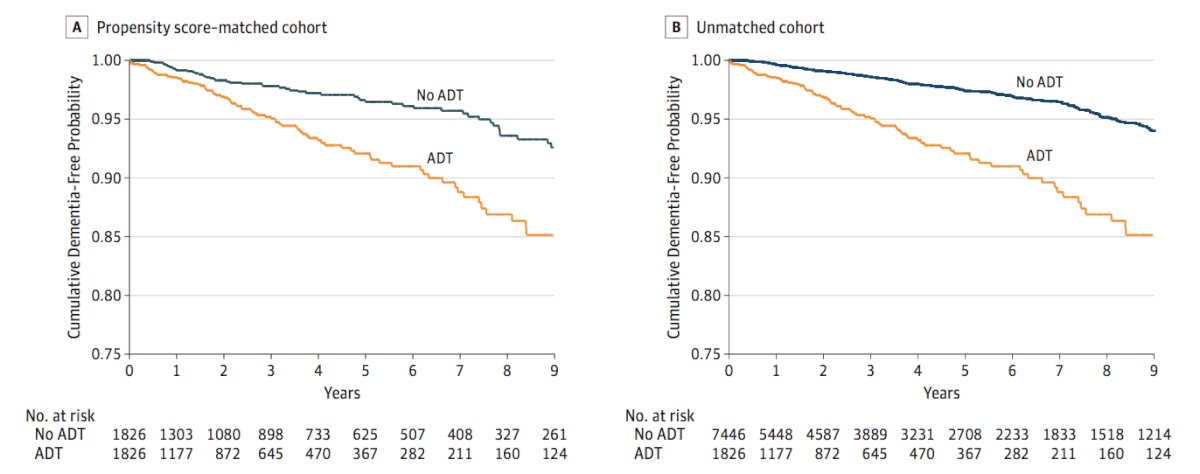

With regards to ADT and dementia, Nead et al.5 assessed the effect of ADT on the risk of dementia among 9,272 men with prostate cancer at a single institution, of which 1,825 (19.7%) were treated with ADT. This study found that there was a statistically significant association between the use of ADT and risk of dementia (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.58-2.99). Similar findings were reported when sensitivity analyses excluded patients with Alzheimer disease (HR 2.32, 95% CI 1.73-3.12). As follows is the Kaplan-Meier curve examining the cumulative probability of remaining dementia free:

The working hypothesis for whether treatments that directly target the androgen receptor cause dementia is that there is likely a complex interaction of genetic effects (AR polymorphisms), drug effects (CNS penetration, potency of AR blockade, etc), and patient effects (age, comorbidity, etc) that leads to cognitive impairment.

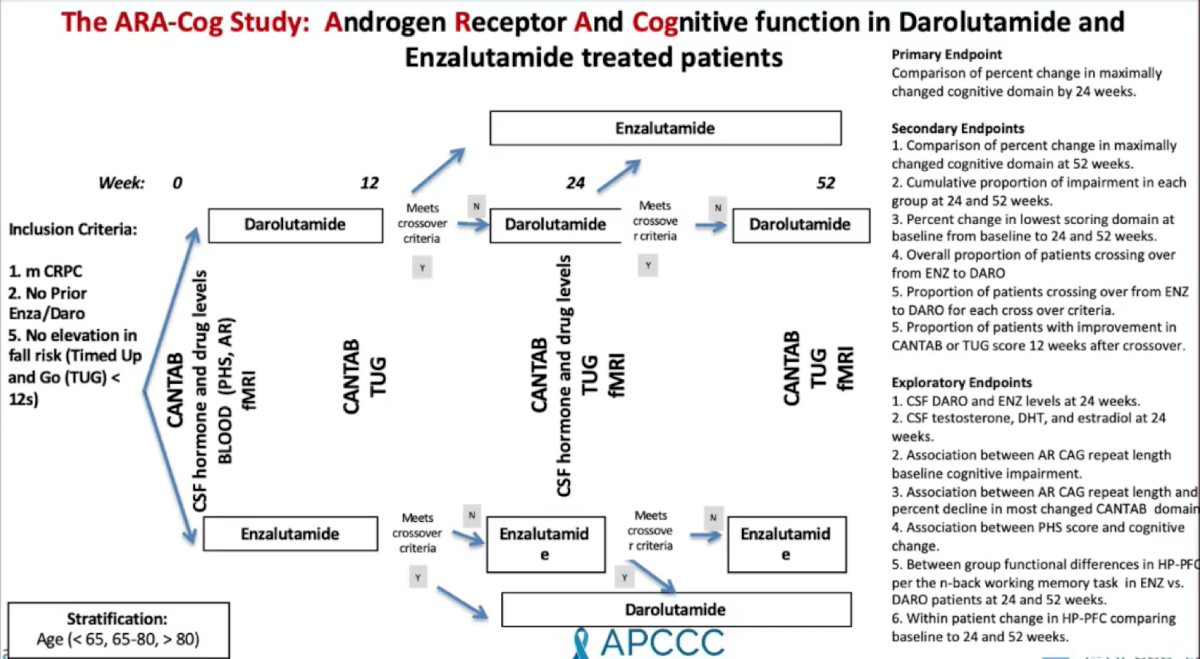

Dr. Ryan concluded his presentation by highlighting that the ARA-Cog study assessing the androgen receptor and cognitive function in darolutamide and enzalutamide treated patients is ongoing and actively recruiting patients:

Presented by: Charles Ryan, MD, President and CEO The Prostate Cancer Foundation, Santa Monica, CA; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2022 Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) Annual Hybrid Meeting, Lugano, Switzerland, Thurs, Apr 28 – Sat, Apr 30, 2022.

References:- Fervaha G, Izard JP, Tripp DA, et al. Depression and prostate cancer: A focused review for the clinician. Urol Oncol. 2019 Apr;37(4):282-288.

- Prasad SM, Eggener SE, Lipsitz SR, et al. Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and mortality of men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Aug 10;32(23):2471-2478.

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016 Dec;30(12):1181-1197.

- Gonzalez BD, Jim HSL, Booth-Jones M, et al. Course and Predictors of Cognitive Function in Patients with Prostate Cancer Receiving Androgen-Deprivation Therapy: A Controlled Comparison. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jun 20;33(18):2021-2027.

- Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C, et al. Association between androgen deprivation therapy and risk of dementia. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):49-55.