(UroToday.com) The 2021 European Society of Medical Oncology’s (EMSO) annual congress included a proffered paper session in non-prostate genitourinary tumors, as well as a discussant presentation by Dr. Brian Rini discussing maintaining efficacy and improving quality of life in the delivery of RCC therapy. Dr. Rini discussed three excellent abstracts: “Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for patients with RCC: Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in KEYNOTE-564” by Dr. Toni Choueiri, “Nivolumab in combination with alternatively scheduled ipilimumab in first-line treatment of patients with advanced RCC: A randomized phase II trial (PRISM)” by Dr. Naveen Vasudev, and “STAR: A Randomized Multi-Stage Phase II/III Trial of Standard first-line therapy (sunitinib or pazopanib) Comparing Temporary Cessation with Allowing Continuation, in the treatment of locally advanced and/or metastatic RCC” by Dr. Janet Brown.

Dr. Rini emphasized that data from KEYNOTE-564 demonstrates that adjuvant pembrolizumab reduces disease recurrence versus placebo in high-risk patients with RCC with a HR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.53-0.87) [1]. In the health-related quality of life presentation at ESMO from KEYNOTE-564, least square mean change in FKSI-DRS score was −1.12 (95% CI, −1.53-−0.71) with pembrolizumab vs −0.45 (95% CI, −0.84-−0.05) with placebo, both of which were below the threshold of ≥3 for clinically meaningful change in FKSI-DRS:

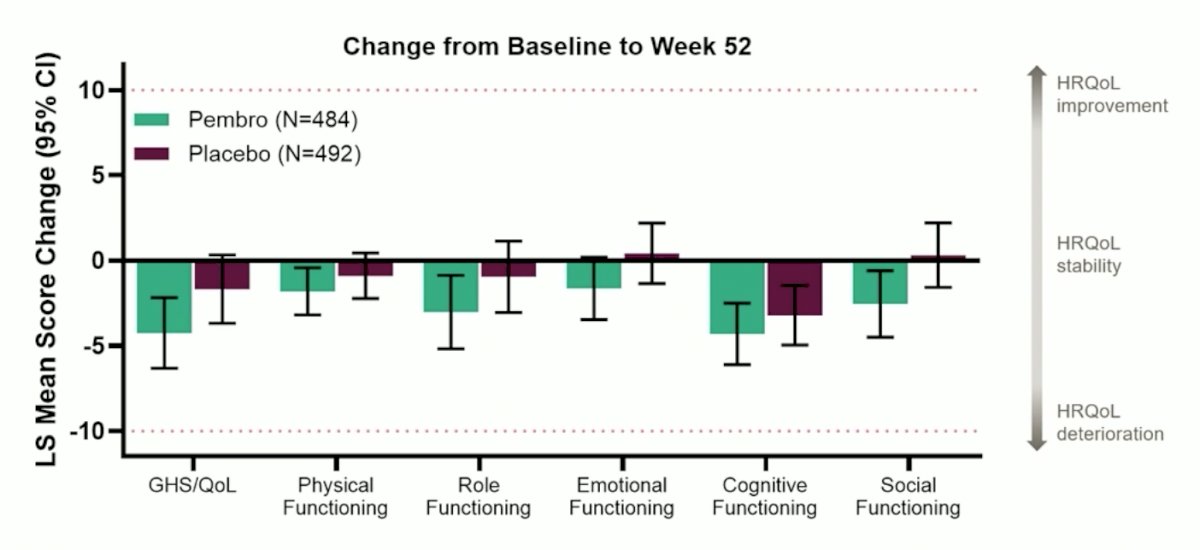

Additionally, the mean score change for both arms for EORTC-QLQ-C30 was below the clinically meaningful change threshold of ≥10 for all domains:

Dr. Rini notes that we may need to be cautious when interpreting these results, given that the threshold for meaningful change from baseline (dotted line) was derived from 141 RCC patients (only 1/3 of those on therapy) and estimated based on old literature in non-cancer patients (FKSI) and supportive care needs within 8 weeks after breast/colorectal surgery involving ~40 observations with wide variation across EORTC domains. Dr. Rini’s conclusions for KEYNOTE-564 are as follows:

- It is not surprising that single-agent pembrolizumab is well-tolerated with minimal effects on group quality of life, however not captured are individual patients with significant/lifelong immure-related adverse events or treatment-related deaths in a population of healthy patients, some of whom were not destined for recurrence

- Certainly, quality of life is important, but quality of life instruments do not accurately capture quality of life, especially with immunotherapy and in the adjuvant setting. For example, FKSI-DRS asks about hematuria and bone pain (the ‘D’ stands for disease), whereas EORTC-QLQ-30 asks if the patient feels tense, depressed, or irritable, and the threshold for minimally important difference is speculative at best

- These instruments mostly capture symptoms related to advanced cancer, and thus it is somewhat surprising that pembrolizumab scores were worse given the DFS benefit

- The decision to use pembrolizumab in the adjuvant RCC setting will come down to individual patient assessment of benefit/risk, including pending data regarding prevention of recurrence and OS benefit versus potential for rare/serious adverse events

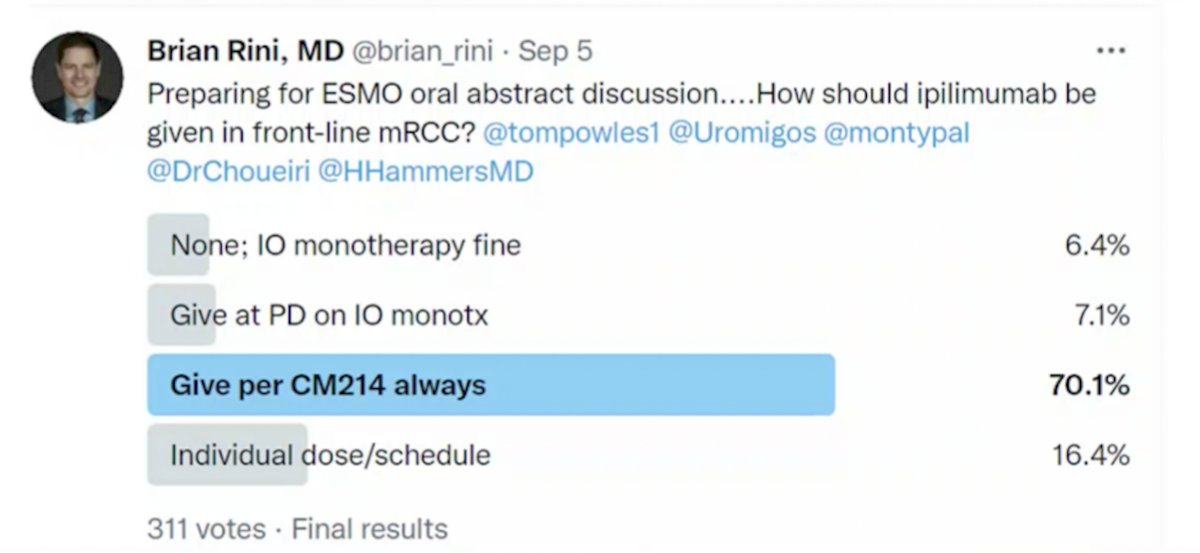

Discussing the PRISM trial next, Dr. Rini asks: Can dose/schedule of therapy be altered to improve patient quality of life while maintaining efficacy? More specifically, how much ipilimumab is needed for optimal outcome in front-line metastatic RCC? To assess the GU oncology community’s thoughts on this topic he conducted a Twitter poll, with the following answer options: (i) none, immunotherapy monotherapy is fine, (ii) give at progressive disease on immunotherapy monotherapy, (iii) give per CheckMate 214 always, and (iv) individual dose/schedule. As follows are the results of his Twitter poll, favoring dosing per the CheckMate 214 protocol:

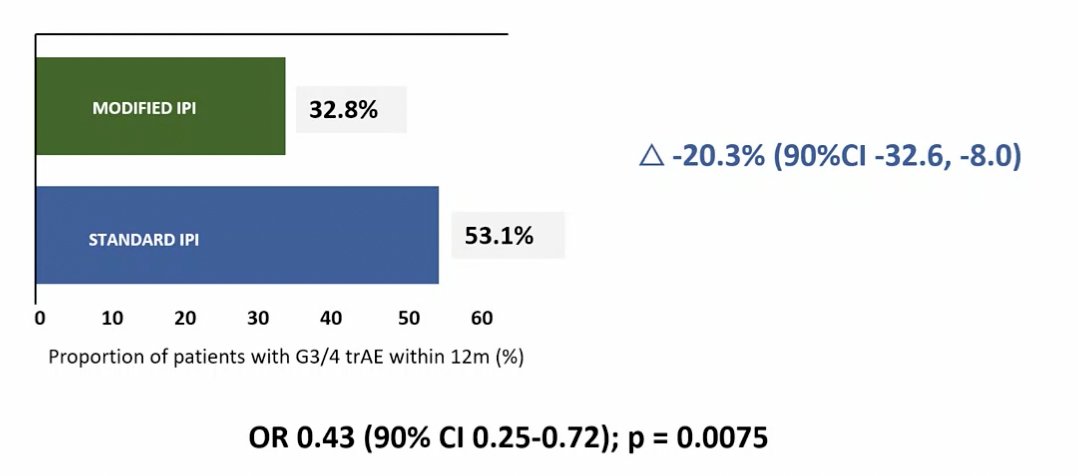

The PRISM trial found that giving ipilimumab 12-weekly, instead of 3-weekly, in combination with nivolumab, was associated with a clinically significant reduction in rates of grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (33% versus 53%). Median PFS, ORR, duration of response, and 12-month landmark OS results were comparable between treatment arms.

Dr. Rini agrees that the less frequent ipilimumab schedule led to less toxicity and efficacy was reasonably well preserved. He notes that giving ipilimumab later in patients with stable disease/progressive disease on nivolumab monotherapy does have precedent, having been tested in HCRN GU16-260, OMNIVORE, and TITAN RCC, as summarized in the following table:

Dr. Rini notes that there are also lessons to be learned from the melanoma literature. Among patients that had two doses of nivolumab (1 mg/kg) + ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) but had subsequent growth of >4% at week 6, none of the patients with tumor growth at week 6 had a subsequent RECIST response. Preliminary correlative data suggests that immunologic effects occur after dose 1 and do not increase thereafter. In the CheckMate 511 trial randomizing advanced melanoma patients to front-line nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg q3 weeks x 4 doses versus nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg q3 weeks x 4 doses, significantly less grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events were noted in the nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg with similar PFS/OS. Dr. Rini suggests that modifying ipilimumab doses can reduce toxicity and is unlikely to reduce short-term efficacy and that in clinical practice this might mean delaying/omitting later ipilimumab doses if there is significant toxicity and especially if the patient is responding.

Dr. Rini then discussed the STAR trial, asking the question: Can dose/schedule of therapy be altered to improve patient quality of life while maintaining efficacy? Dr. Rini’s group was part of a phase II trial that assessed feasibility and clinical outcomes with intermittent sunitinib dosing in patients with metastatic RCC [2]. Patients with treatment-naïve, clear cell mRCC were treated with four cycles of sunitinib (50 mg once per day, 4 weeks of receiving treatment followed by 2 weeks of no treatment). Patients with a ≥ 10% reduction in tumor burden after four cycles had sunitinib held, with restaging scans performed every two cycles. Sunitinib was reinitiated for two cycles in those patients with an increase in tumor burden by ≥ 10% and again held with ≥ 10% tumor burden reduction. Among 37 patients enrolled, 20 were eligible for intermittent therapy and all patients entered the intermittent phase. The objective response rate was 46% after the first four cycles of therapy. The median increase in tumor burden during the periods of sunitinib was 1.6 cm (range, -2.9 to 3.4 cm) compared with the tumor burden immediately before stopping sunitinib.

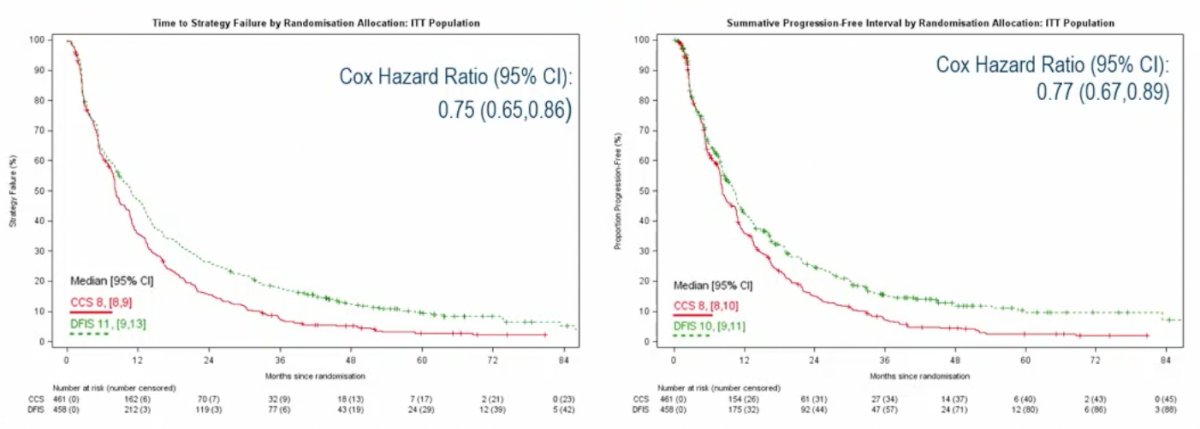

In the STAR trial, Dr. Rini highlighted that 56% of patients came off study prior to starting the intermittent strategy, with the population typical for metastatic RCC patients, but skewed slightly to IMDC favorable/intermediate risk. The median number of breaks was 1 (only 1 treatment break was mandated), with 42% of intermittent patients with >1 break. The median duration of treatment breaks was 12.4 weeks, and there is no data yet on the median tumor growth during breaks. Dr. Rini highlighted several important points for assessing the TKI efficacy curves:

- The intermittent strategy tolerates progressive disease and thus that may account for the time to strategy failure advantage

- Per protocol analysis did not meet the threshold for non-inferiority but analyzed all patients and not just patients who made it to continuous versus intermittent treatment

Ultimately, the intermittent TKI strategy resulted in less toxicity and cost-saving, with non-inferior QALYs. Dr. Rini notes that for most strategies, including intermittent TKIs, the approach needs to be individualized. Waiting until RECIST progressive disease to restart the TKI is unlikely to be the right approach for many patients depending on the disease burden and sites of metastases. The right duration of a treatment break also depends on the inherent growth rate of a given patient’s disease. At the very least, periodic short breaks (ie. 3 days) off TKI can really help mitigate chronic TKI toxicity. Importantly, the same principles apply to TKI management when part of an immunotherapy/TKI regimen or TKI monotherapy in the refractory setting.

Dr. Rini concluded his discussant presentation of these three abstracts with the following take-home messages:

- Maintaining a patient’s quality of life while optimizing therapeutic efficacy is the fundamental goal in oncology

- Current quality of life measurement tools are inadequate to capture the nuances of modern therapy and results should be interpreted with extreme caution

- Intermittent/dose modifying strategies can and should be individualized and incorporated into clinical practice

Presented by: Brian Rini, MD, Chief of Clinical Trials Professor of Medicine, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Congress 2021, Thursday, Sep 16, 2021 – Tuesday, Sep 21, 2021.

References:

- Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab after Nephrectomy in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 19;385(8):683-694.

- Ornstein MC, Wood LS, Elson P, et al. A Phase II Study of Intermittent Sunitinib in Previously Untreated Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jun 1;35(16): 1764-1769.