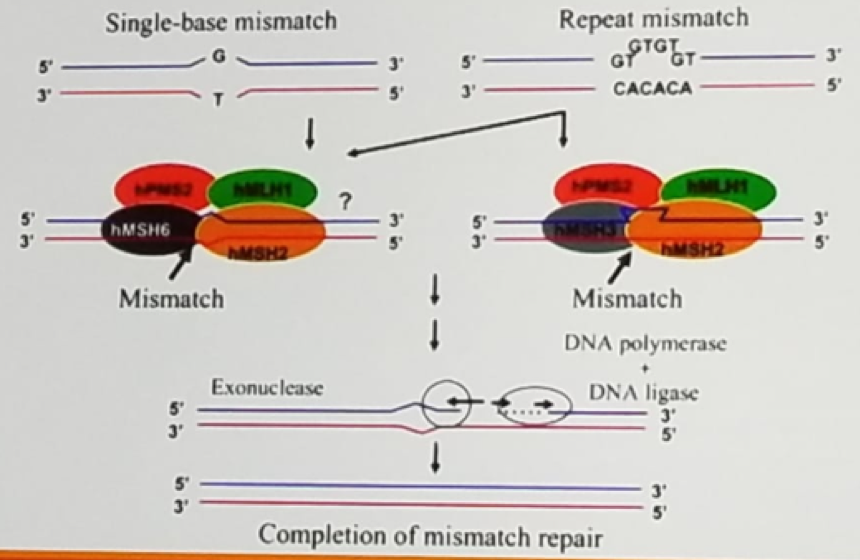

Figure 1 – DNA mismatch repair:

Error in the DNA repair process can lead to instability of microsatellites, which are tracts of repetitive DNA with repeated motifs ranging in length from 2-5 base-pairs, repeated 5-50 times. In colorectal cancer tissue of Lynch syndrome tumors demonstrate allelic shifts in 5-7 microsatellite markers, which can be identified using PCR.

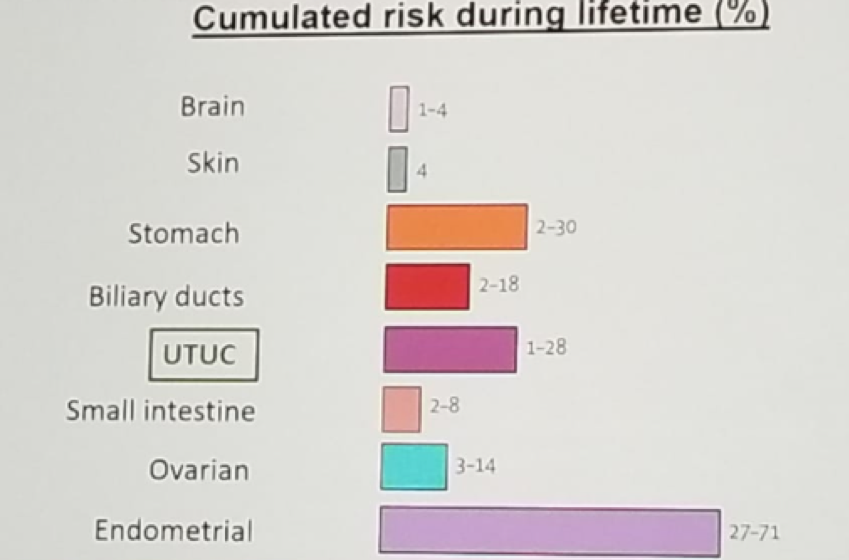

Lynch syndrome tumor spectrum include colon, brain, skin, gastric, biliary ducts, upper tract, small intestine, ovarian and endometrial (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Lynch syndrome tumor spectrum:

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma is usually not first cancer manifested in Lynch syndrome patients. It usually occurs 15 years following the presentation of first cancer. MSH2 mutation is must common mutation in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. The mean age is 62 (vs. 70 for sporadic cancer), and there is an equal gender ratio. 51% are in the ureter (Compared to 65% in the sporadic cases) and they have a similar high-grade potential.

The clinical criteria used to suspect patients of having Lynch syndrome are the Amsterdam 2 criteria, which are best remembered using the 3:2:1 guideline, which is defined as 3 relatives affected, 2 successive generation and 1 first degree relative of the other 2 diagnosed before the age of 50. There are concerns that these clinical criteria are still too strict and may miss LS patients (72% sensitivity).

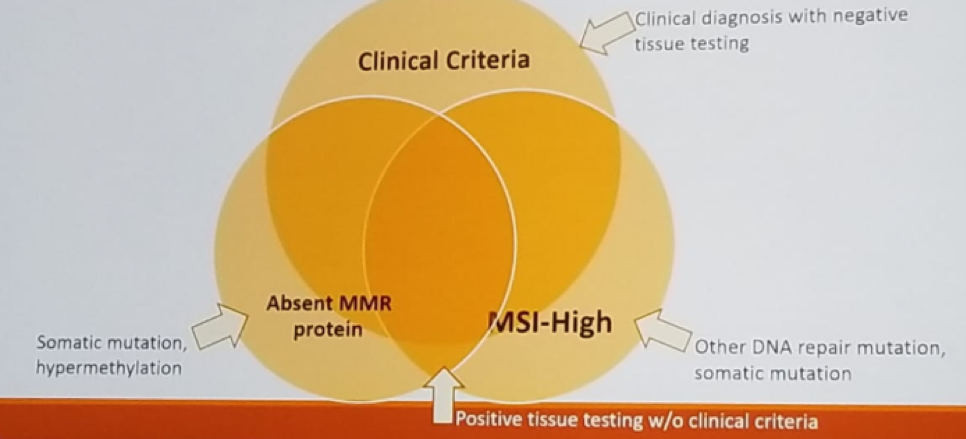

Lynch syndrome can be diagnosed with immunohistochemistry with stains existing for each of the mismatch repair proteins. The absence of mismatch repair protein expression suggests Lynch syndrome. Lynch syndrome can also be diagnosed by microsatellite instability (MSI) through the usage of PCR on tumor and normal tissue. Results are shown as MSI-high: 30% or more alleles shifted, MSI -low: <30% alleles shifted, with an unknown clinical significance, or MSI -stable: 0 alleles shifted. However, approximately 10% of Lynch syndrome-related colorectal cancers demonstrate intact mismatch repair protein expression. MSI testing has only been validated for colorectal cancer tissues, not endometrial, upper tract disease or any other Lynch syndrome-associated tumor. It is very possible that different host tissue will have different microsatellite markers.

Dr. Matin noted that immunohistochemistry, PCR and clinical criteria are complementary to each other, as can be seen in figure 3.

Figure 3 – Immunohistochemistry, PCR and clinical criteria are complementary:

Of note, it crucial to remember that MSI-high does not automatically equal to the presence of Lynch syndrome. Data have shown that 45% of those diagnosed with Lynch syndrome did not meet clinical criteria. Therefore, some suggest that all MSI-high tumor patients need to be tested for Lynch syndrome.

Genetic counseling is extremely important in the diagnosis and follow-up of Lynch syndrome patients. It provides a risk assessment based on personal /family history. It also makes recommendations for patients and family members based on the results of genetic testing and family history. It works well with laboratory and insurance companies as needed regarding coverage of genetic testing.

Lynch syndrome patients need to be screened frequently for all other Lynch syndrome-associated tumors. MSI-high tumors have a greater sensitivity to checkpoint blockade and potential higher chemo-sensitivity. Anti PD-L1 therapy should be the first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with deficient mismatch repair genes or MSI-high.

Universal point of care testing is routine in colorectal cancer and has been shown to be cost-effective, with an increased rate of diagnosis, and well-accepted by patients and their families. This should also be done for endometrial cancer, and using immunohistochemistry has a greater acceptance than PCR. However, in upper tract disease, it has not been the standard of care. In a study by Metcalfe MH et al. 1 5.2% of all upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients were found to have Lynch syndrome, and 13.9% were found to be possible Lynch syndrome patients or other inheritable mutation. Amsterdam 2 criteria and immunohistochemistry testing captured all diagnosed upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients. No single test managed to capture all testing. MSH2 and MSH6 were the most common mutations. There is currently an ongoing prospective trial trying to assess whether all patients with sporadic upper tract urothelial carcinoma should undergo screening for Lynch syndrome.

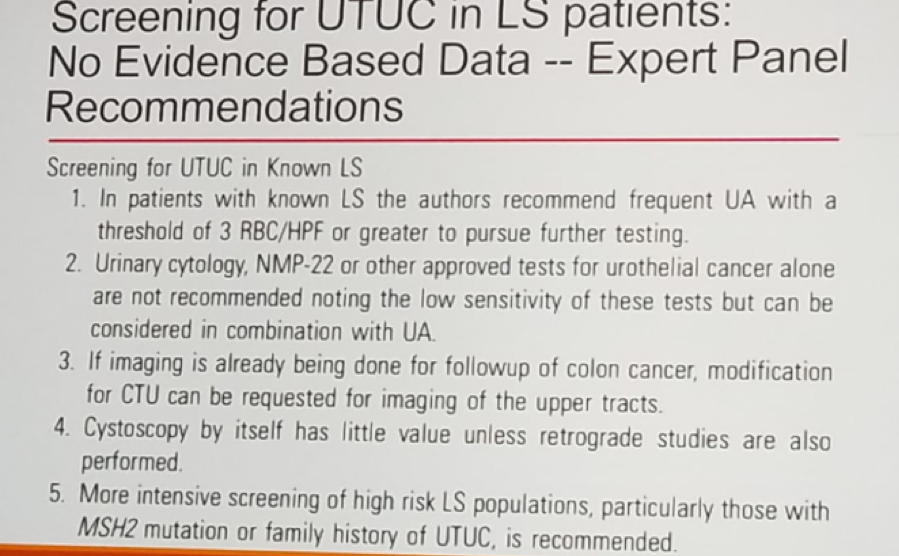

Guidelines for screening for upper tract urothelial carcinoma in Lynch syndrome patients currently does not exist, but there are expert panel recommendations, as seen in figure 42.

Figure 4:

Summarizing his talk, Dr. Matin gave some practice points: For any new upper tract urothelial carcinoma patient it is critical to obtain a broad personal and familial oncologic history, and not just involving genitourinary cancers. The Amsterdam 2 criteria with the 3-2-1 principle should be applied. Patients may have Lynch syndrome even with negative clinical screening. Immunohistochemistry should be done if there is tumor available, but if not, then the patient needs to be sent to genetic testing. Lastly, screening and early diagnosis of Lynch syndrome will have major implications for patients and their family members.

References:

1. Metcalfe MJ et al. J Urol 2017

2. Mork M et al. J Urol 2013

Presented by: Surena F. Matin, MD Anderson Cancer Center

Written By: Hanan Goldberg, MD, Urologic Oncology Fellow (SUO), University of Toronto, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre @GoldbergHanan, at the 19th Annual Meeting of the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO), November 28-30, 2018 – Phoenix, Arizona